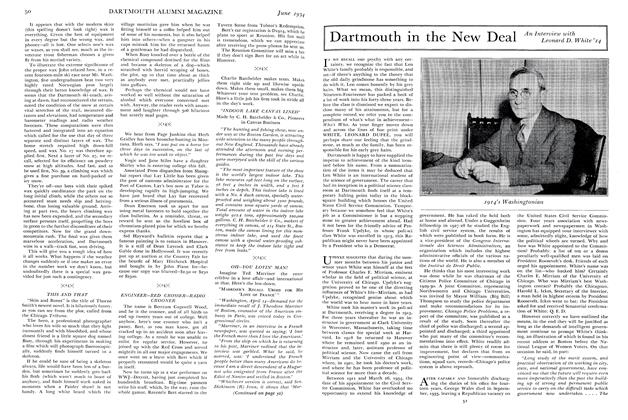

The Nation's Huge Revenue Problems Are in the Lap of John Sullivan '21 at Washington

Long before the New Deal set up shop in Washington, two of its ranking officials met in Berlin under unusual circumstances. It happened this way.

Not long after John Sullivan graduated from Dartmouth in 1921, he took a postgraduate course around the European countryside. In Paris, he became acquainted with John Hollis, Cornell graduate,

ate, and son of Henry Hollis, first New Hampshire Democrat to win a seat in the U. S. Senate. Hollis and Sullivan picked up a second-hand motorcycle, with a sidecar, and set out to swing the Continent. Arriving in pre-Hitler Berlin, they found their knowledge of German totally unservice- able. It was a happy accident, thereforethat brought them into touch with Leon Henderson who spoke, and still speaks, fluent German.

Sullivan and Henderson continued the European junket via sidecar when Hollis was forced to make connections with the liner that had retained him as swimming instructor. Today the two men, good friends, hold responsible offices in the Roosevelt Administration—Henderson is a member of the Advisory Commission for the Council of National Defense, and a member of the Securities and Exchange Commission, while Sullivan is Assistant Secretary of the U. S. Treasury.

When Henderson told me about the episode abroad, I said to John: "It must have been your original contact with the New Deal." In a whip-lash of Irish wit, John replied: "Not mine, Henderson's!"

Of course, it won't do to read too much into John's off-hand crack, but he may have ad-libbed us into an idea. In short, today's philosophy of federal government is shaped by the men who are administrators within the New Deal executive establishment. Analysts of the Washington political scene, almost without exception, category Henderson with the left-wingers. If, as John's crack suggests, Henderson's dose of New Dealism was spooned not from Henderson's but from Sullivan's bottle, we would have to seat John not left of center, but further over.

However, there's another, and I believe, less disconcerting—at least to some citizens —interpretation of John's rejoinder. It is this. If, without being specific, we will agree that New Deal philosophy is liberal, as opposed to conservative, there must also be admitted varying shades and colorings of liberalism. What John really meant to imply, then, was that although both he and Henderson were liberals, he, not Henderson, was the true repository of New Deal liberalism.

SULLIVAN INFLUENCES POLICY

Our conjectures on Sullivan's tendencies have not been lost on those who realize that the fiscal policy of the United States, for the immediate future at least, may swing largely around the axis of John's thinking. As Assistant Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, he is responsible for developing ways and means of financing the government's program. He is the federal tax expert. The government has embarked upon a gigantic defense program that will cost billions of dollars. Who will pay for it? When? How? Meanwhile, our farmers have lost a tremendous export market, due to war in Europe and Asia. How will they be compensated for their loss? Who will pay? How? When? Is it proposed that the regular budget be balanced, the normal costs of government? If so, how? When and where will the tax burden fall? Somebody's going to pay the freight, and in large measure the recommendations made by Sullivan will determine policy on this point.

When the discussion gets round to taxes, the average man quickly realizes his disadvantageous position in comparison with that of well organized groups. Business, compact and solidly marshalled in trade associations, raises the most vehement voice heard at the tax table. If we will accept, further, New Deal allegations that it has championed human rights as against property rights, we may have uncovered a reason for the protest voice of business. What Sullivan's revenue proposals will be, therefore, is of vital interest to business. Although considerably less articulate about it, Mr. and Mrs. John Q. Public are no less interested because they recently returned the Roosevelt Administration—and our John included—to power to speak for them, among other places, at the tax table.

When we look at the record for some guidepost to John's thinking on the subject of taxation, we discover a background fitted nicely to your stereotype of a typical anti-Rooseveltian. In the first instance, he's a lawyer—often the theme of FDR censure. Further, he's a corporation lawyer. Finally, and most startlingly, he was an associate counsel for the Hoosac Mills Corporation which, in 1936, carried its case against the New Deal Agricultural Adjustment Act to the Supreme Court where it was declared unconstitutional! All of which ought to be solace enough for business as it thumbs through the pages of the Assistant Secretary's past for a tip-off to mental predispositions with respect to revenue raising.

Tied to such a conservative, near-reactionary economic biography, how does it happen that Johnnie now sits so close to the White House that he can look across at its wide-throated East Gate from the windows of his office in the Treasury Building?

If you want a job done right, you hire a man who knows something about the job. If you need a man to drive the Nation to greater productive capacity to establish an "arsenal for democracy," you retain a tough-minded Bill Knudsen. If the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was once a corporation lawyer, he is therefore better equipped to understand, and pass judgment on, laws governing a highly industrialized civilization. Even casual study of Supreme Court decisions over the years proves that the so-called conservative background of Charles Evans Hughes interferes not at all with his so-called liberal inclinations. By such ABC criteria, then, is not Sullivan better fortified to protect public interest in the preparation of a national revenue program because he is intimately familiar with the problems of corporate management? If business is taxed out of existence, unemployment figures are not likely to improve. Conversely, if business gets rich on a defense program, public welfare will have been ill-served.

When we examine more sharply the contents of Sullivan's personal dossier, we find documentary assurance that his tax program will spell out levies in accordance with ability to pay. Further, we uncover ample reason why his office overlooks the East Gate.

There are other reasons, of course. Less important reasons. John is, and always has been, a Democrat—if that word, or its reputed antonym, Republican, connotes anything to anybody any longer. In 1934, as a Democrat, he ran for Governor of New Hampshire—once a nominally Republican State—against Styles Bridges. He lost—by 2400 votes. He ran again for the same office in 1938 against Francis Murphy, and took more of a trimming. If that proves anything, it proves that John can take his lickings—and come up smiling. He came up with a grin two years later when he stumped (in Wall Street) for Frank Roosevelt, and saw his champion defeat Wendell Willkie. Reason enough why one New Deal anchor man told me John was tops in this Administration because: "He's a good fighter."

That's the Irish in him. You can't stand up under ten solid weeks of testifying before Congressional committees if you're afraid you'll get your ears pinned back. John took over as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in January 1940. Within a few weeks, House and Senate committees asked him to defend the First Revenue Act of 1940. Right on its heels followed the Excess Profits Tax—and more testifying. He couldn't duck all the blows, but he acquitted himself gallantly and intelligently. When it was all over, the columnists, Alsop and Kintner, wrote that "he has remained popular with Republican and Democratic committee members, even though he has stuck to his theories .... one of the most respected and popular Treasury officials."

January wasn't a particularly happy month for me to call on John Sullivan. Not that he wouldn't talk—he couldn't. I wanted him to tell us how we were going to pay for the defense program. He wouldn't even give me off-the-record dope. It was not difficult to understand why. The President's Message on the State of the Union was in the offing, his annual budget message was just around the corner—it was no time for a lieutenant to be sounding off ahead of his captain. He did say something, however, with a broad sweep to it that I liked. It wasn't new, nor was it outstandingly brilliant, but it was catholic and democratic.

"Every ship, every plane, every tank, every gun we acquire for national defense is going to be paid for one hundred cents on the dollar. It's going to be paid for by you and me and the rest of the American people, and we are going to pay it eventually through taxes. In doing this, we will do it in a manner that least disrupts the economic life of the Nation.

"I believe that there can be in America no security, no lasting prosperity unless all types of people in all sections of America join in that security and share in that prosperity. That was the lesson and the moral of the thirties, and for the forties it will be well to remember them. If we forget them, we invite peril to the Nation and disaster to ourselves. There just can't be any brokers' yachts unless the customers have plenty of rowboats."

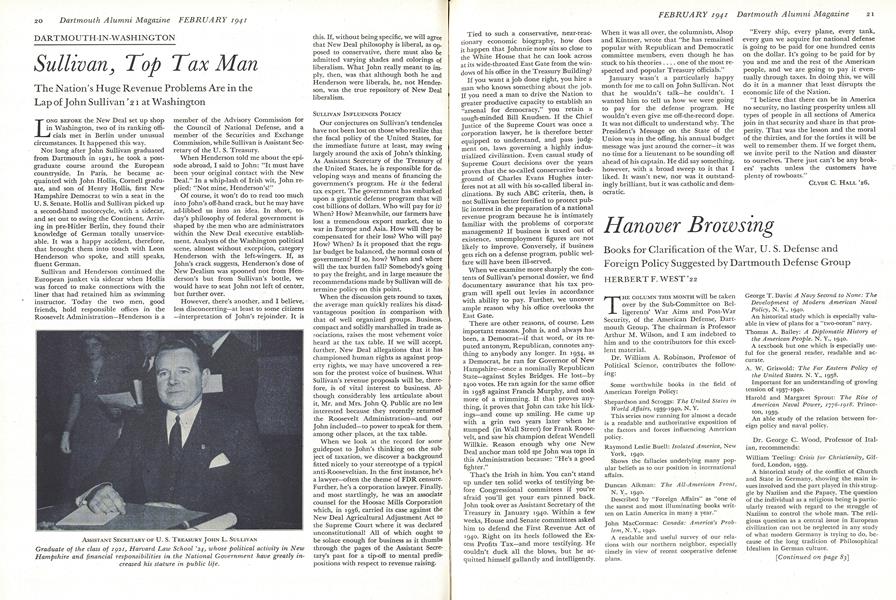

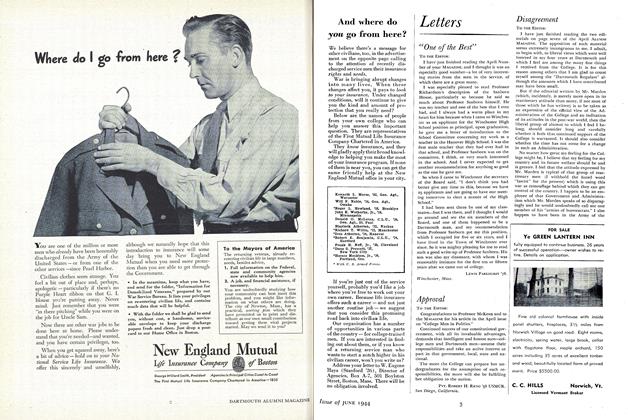

ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF U. S. TREASURY JOHN L. SULLIVAN Graduate of the class of 1921, Harvard Law School '24, whose political activity in NewHampshire and financial responsibilities in the National Government have greatly increased his stature in public life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleClassicist Not Without Honor

February 1941 By Donald Bartlett '24 -

Article

ArticleA Kind and Comfortable House

February 1941 By S. C. H. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1941 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924*

February 1941 By ALFRED A. ADAMS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939*

February 1941 By ROBERT W. GIBSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

February 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR.

Clyde C. Hall '26

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1944 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal Dartmouth in the New Deal

February 1934 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal

March 1934 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticlePreservation of Democracy

January 1941 By CLYDE C. HALL '26 -

Article

ArticlePresident Hopkins' Defense Work

April 1941 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal

June 1934 By Leonard D. White '14, Clyde C. Hall '26

Article

-

Article

ArticleGOVERNOR-ELECT BROWN MADE A LIFE TRUSTEE

December 1920 -

Article

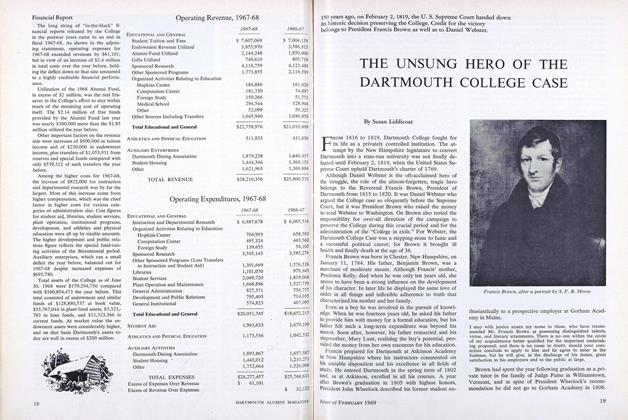

ArticleFinancial Report

FEBRUARY 1969 -

Article

ArticleA Grew Prize from England

May 1956 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleADDRESS AT THE OPENING EXERCISE OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SEPTEMBER 23, 1926

NOVEMBER, 1926 By Dean Craven Laycock -

Article

ArticleUndergraduate Lingo

April 1956 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Article

ArticleThe Butcker, the Baker, the Russian-Class Taker

NOVEMBER 1998 By Noel Perrin