An Interviewwith Fred Brown '03

Time: 1922. Place: City room of any Boston newspaper.

Characters: Cub reporter and old political dopester. Curtain.

Cub: Say, New Hampshire votes for a governor this year.

O.p.d.: (Stifling a yawn) Aw that's not news. New Hampshire's been doing that for a helluva long time, young fella, and they've changed their minds only once in sixty years. Except for one term they've returned a Republican ever since 1873. Take it from this old timer, your money's safe on Goodnow.

Cub: Is he the Republican?

O.p.d.: Who'd you think he was, the Democrat? Go out in the morgue and dig up a photo and biography of Goodnow, write the story—leaving space for the vote count, and forget all about New Hampshire. It's in the bag.

When the same piece of soil has been sown with a particular crop for several seasons, its vitality is drained, its product is starved. A different crop puts new life into the soil. This bit of husbandry hadn't occurred to the old political dopester. So the gullible cub dropped his prepared story into the wastebasket, hopped a train bound north where news was indeed breaking with the election of a Democrat.

It was about six o'clock in the evening when he walked down the main street in the home town of New Hampshire's new chief executive. Sidling up to an old inhabitant, he asked where he might find the governor. In that homely, nasal tone of voice—which makes anyone who loves New Hampshire homesick—the inhabitant, pulling out his watch, replied: "Wal, le's see. 'Bout six o'clock, haint it? I'll allow as how you'll find him over thar in thet lunch-cart eatin' his dinner." A few minutes later the leporter climbed up on a stool beside the first Democrat save one to be elected Governor of New Hampshire in sixty years. Particularly to you of '03 does it seem unnecessary to say that he was Fred Herbert Brown. Today he represents the Granite State in the United States Senate.

Had you told Fred, back at the turn of |he century when he was catching for the artmouth baseball team, that somewhere on» in the seventh inning of his life he would hang his hat in the Senate Office mlding, he might have left the imprint 0 a baseball's stitches on your hide. The game of politics was at that time as removed from, as the game of baseball was close to, his life. For nearly a decade he Played baseball to the exclusion of everything else. Until his throwing arm pained him to a degree which made him writhe on 1 e Br°und,8r°und, he was to wipe 'em off the base Paths for Springfield, Providence, and Jersey City in the Eastern, and Boston in the National League. Fred, however, got as much kick from college baseball as he did from the big time. He tells one story which should be made part of the record:

"We were playing the first of a two-game series with Williams. It was the ninth linning and Dartmouth was leading 6-4. They got the bases loaded when our shortstop picked up a liner and heaved it over my head. It went back into the Williams crowd, and when I attempted to retrieve it, they kicked it all over the lot. Williams won 7-6. We were stopping at North Adams, and driving over there on a buckboard that night, we were so damned sore we wouldn't speak to each other. I went to bed in a mood fit to have choked somebody.

"I was awakened sometime around five or six the next morning by the sound of loud music. Rubbing the sleep from my eyes, I went to the window. Talk about college spirit! Man alive! Down there in the street, under our windows, was the Dartmouth band and two or three hundred students yelling their heads off. I'll never forget that sight. Those fellows had pulled out of White River Junction at midnight with no more idea how or when they'd get back than the man in the moon. It was Dartmouth spirit in the raw. 'Boy,' I said to myself, 'We'll lick 'em today.' And we did—licked the pants off 'em! We piled up eleven runs, while Williams scored only twice."

RELUCTANTLY, Brown foresook the diamond when his pegging wing refused to respond. Between innings he had studied law at Boston University, and in 1907 he passed the New Hampshire bar. Soon thereafter he entered the law office of James A. Edgerly of Somersworth, about thirty miles down-state from Ossipee where Fred was born on April 12, 1879. He had played some town-team baseball at Somersworth and its folk knew him well—they not only knew him, but liked him so well that they elected him mayor in 1914 and kept him in that office every year until 1923. The town might have had him yet if the state hadn't decided to take him over. Winant, who defeated him in the gubernatorial race of '24, realized that his services were well-nigh indispensable to good government and appointed him to a six-year term on the Public Service Commission. Though defeated later, Winant returned in '31 and reappointed Fred for another six-year period.

Along came 1932. The soil hadn't been yielding any too well. It was the nation this time that decided it was time to plant a different crop. A new seed, called Roosevelt, was found. It sounded not unlike one they had tried before with good results. Tirelessly, Brown spread the Roosevelt seed over the length and breadth of New Hampshire. From the beginning he backed his man against the field. He tossed his own hat into the ring and defeated Senator George H. Moses '90 to keep alive a Dartmouth tradition instituted in 1827 by Daniel Webster.

UNLIKE HIS distinguished predecessor in the Senate, Fred is not conspicuous in the headlines. He doesn't say much, but anyone who knows legislative Washington knows that the work isn't done on the Senate floor. Shirt sleeves are rolled up in committee rooms. Fred's assignments are on the rather important commerce, manufactures, post offices and post roads, interstate commerce, and privileges and elec- tions committees. If he may be said to have any pet legislation it is in connection with the power and light business. His interest therein comes as a direct result of his work on the New Hampshire Public Service Commission. He believes rates to the consumer aren't just as they should be, and says: "If I get a chance, I'm going to do something about it."

Brown sidelights: When he was elected governor, the Eagle, swank Concord hotel and stopping place of New Hampshire's elite wrote him saying, in effect, that the gubernatorial suite would be reserved for him. In reply Fred thanked them, saying that the Phenix, Concord's other hotel, had served him well while he was United States District Attorney, and he thought it would be all right now that he was governor His fraternity: Delta Kappa Epsilon For several years Fred must have been something of an eligible bachelor. He didn't marry until 1925. When, however, Miss Edna McHarg of Colebrook, N. H., came along, his resistance broke down and they were married on May sixteenth of that year. They make their home in Somers-worth where he votes, and have a house in Concord where she votes. They have no children List, among avocations, fishing and watching baseball. He sees no team capable of licking the Senators in the American League Last time in Hanover, 1923—his twentieth Closest Dartmouth friend, William Nathaniel Rogers 'ls, Congressman from the First New Hampshire District Somers worth, Fred's home town, has been Democratic for the past 28 years without a break. . . . . Interesting fact about George H. Duncan, his secretary—awarded honorary Master of Arts degree by Dartmouth, June, 1932-

Finally, Fred stands about five feet nine inches, weighs over 200 pounds, and you'd never want to meet a more good-natured, unpretentious fellow. There are those who do not understand Dartmouth when she sings about her granite. But Dartmouth men understand. They have in mind men such as Fred Brown—sturdy, close to the soil, hard-headed Yankee—when they sing about ". . . . the granite of New Hampshire in their muscles and their brains."

New Hampshire Democrat

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1934 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1933

March 1934 By John S. Monagan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

March 1934 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

March 1934 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

March 1934 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleTRIBUTES TO PROFESSOR LINGLEY

March 1934 By Friends and Associates

Clyde C. Hall '26

-

Article

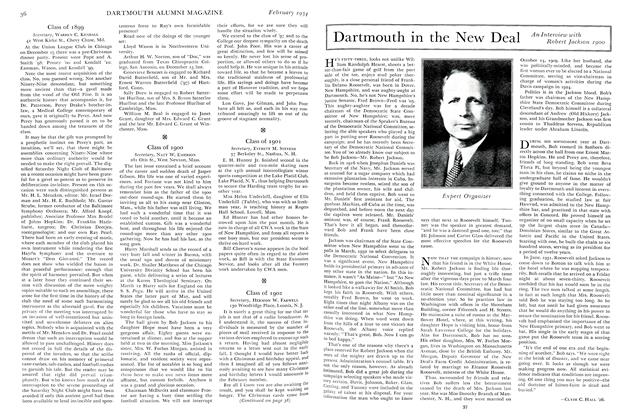

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal Dartmouth in the New Deal

February 1934 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal

May 1934 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticlePreservation of Democracy

January 1941 By CLYDE C. HALL '26 -

Article

ArticleSullivan, Top Tax Man

February 1941 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticlePresident Hopkins' Defense Work

April 1941 By Clyde C. Hall '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the New Deal

June 1934 By Leonard D. White '14, Clyde C. Hall '26