Webster Espoused the Cause of Greece in 1824 With Words of Strange and Notable Timeliness Today

CHURCHILL LATHROP PROFESSOR OF ART

This is an abstract of the importantspeech which Daniel Webster made in Congress on behalf of his own resolution thatrecognition and encouragement be givento Greece by the appointment of a Commissioner from the United States.

The speech deals not only with the struggle of Greece against a powerful oppressor,but also, and this is the real weight of thespeech, with "the great political questionof the age, that between absolute and regulated governments." Mr. Webster isgravely concerned over "new and dangerous combinations (of foreign States) whollysubversive of the liberties of mankind,"and he is forthright and far-sighted in stating the inevitable position on this questionof the United States as a nation of theearth.

With the march of the Axis Powers thisbasic question of absolute or regulated governments is again the vital political issue ofthe day. Mr. Webster's words have a timeliness that it would, indeed, be difficult toexaggerate.

IN DECEMBER 1823 President Monroe sent his annual message to Congress. One paragraph was as follows:

"A strong hope has long been entertained, founded on the heroic struggle of the Greeks, that they would succeed in their contest, and resume their equal station among the nations of the earth. It is believed that the whole civilized world takes a deep interest in their welfare. Although no power has declared in their favor, yet none, according to our information, has taken part against them. Their cause and their name have protected them from dangers which might ere this have overwhelmed any other people. The ordinary calculations of interest, and of acquisition with a view to aggrandizement, which mingle so much in the transactions of nations, seem to have had no effect in regard to them. From the facts which have come to our knowledge, there is good cause to believe that their enemy has lost for ever all dominion over them; that Greece will become again an independent nation."

A few days later Mr. Daniel Webster, Representative from Massachusetts, introduced in the House of Representatives the following resolution:—

"Resolved, That provision ought to be made by law, for defraying the expense incident to the appointment of an Agent or Commissioner to Greece, whenever the President shall deem it expedient to make such an appointment."

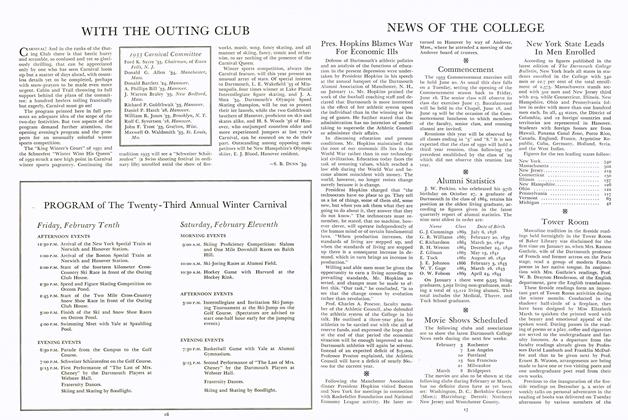

On January 19, 1824 Webster spoke at length to the House in favor of his resolution. An immense audience was present keyed to a high pitch of expectation due to the fame of the speaker and the popularity of his subject. It was a great speech and a great success. He said in part:—

"This free form of government, this popular assembly, the common council held for the common good,—where have we contemplated its earliest models? This practice of free debate and public discussion, the contest of mind with mind, and that popular eloquence, which, if it were now here, on a subject like this, would move the stones of the Capitol,—whose was the language in which all these were first exhibited? Even the edifice in which we assemble, these proportioned columns, this ornamented architecture, all remind us that Greece has existed, and that we, like the rest of mankind, are greatly her debtors.

"I wish to take occasion of the struggle of an interesting and gallant people, in the cause of liberty and Christianity, to draw the attention of the House to the circumstances which have accompanied that struggle, and to the principles which appear to have governed the conduct of the great states of Europe in regard to it; and to the effects and consequences of these principles upon the independence of nations, and especially upon the institutions of free governments. What I have to say of Greece, therefore, concerns the modern, not the ancient; the living, and not the dead.

"I wish to treat the subject on such grounds, exclusively, as are truly American. Let this be, then, purely an American discussion; but let it embrace, nevertheless, everything that fairly concerns America. Let it comprehend, not merely her present advantage, but her permanent interest, her elevated character as one of the free states of the world, and her duty towards those great principles which have hitherto maintained the relative independence of nations, and which have, more especially, made her what she is.

"The nation is prosperous, peaceful, and happy; and I should very reluctantly put its peace, prosperity or happiness at risk. It appears to me, however, that this resolution is strictly conformable to our general policy, and not only consistent with our interests, but even demanded by a large and liberal view of those interests.

"I take it for granted that the policy of this country, springing from the nature of our government and the spirit of all our institutions, is, so far as it respects the interesting questions which agitate the present age, on the side of liberty and enlightened sentiments. We are placed, by our good fortune and the wisdom and valor of our ancestors, in a condition in which we can act no obscure part. Be it for honor, or be it for dishonor, whatever we do is sure to attact the observation of the world.

"It cannot be denied that the great political question of this age is that between absolute and regulated governments. The main controversy is between that absolute rule, which, while it promises to govern well, means, nevertheless, to govern without control, and that constitutional system which restrains sovereign discretion, and asserts that society may claim as matter of right some effective power in the establishment of the laws which are to regulate it.

The spirit of the times sets with a most powerful current in favor of these last mentioned opinions. It is opposed, however, by certain of the great potentates of Europe; and it is opposed on grounds as applicable in one civilized nation as in another, and which would justify such opposition in relation to the United States, as well as in relation to any other state or nation, if time and circumstances should render such opposition expedient.

"Our side of this question is settled for us, even without our own volition. Our history, our situation, our character, necessarily decide our position and our course, before we have even time to ask whether we have an option. Our place is on the side of free institutions. From the earliest settlement of these States, their inhabitants were accustomed, in a greater or less degree, to the enjoyment of the powers of self-government; and for the last half-century they have sustained systems of government entirely representative. This system we are not likely to abandon.

"I will now, Mr. Chairman, advert to those pretensions put forth by the allied sovereigns of Continental Europe, which seem to me calculated, if unresisted, to bring into disrepute the principles of our government, and, indeed, to be wholly incompatible with any degree of national independence. I have a most deep and thorough conviction that a new era has arisen in the world, that new and dangerous combinations are taking place, promulgating doctrines and fraught with consequences wholly subversive in their tendency of the public law of nations and of the general liberties of mankind.

"I begin, Mr. Chairman, by drawing your attention to the treaty concluded at Paris in September 1815 between Russia, Prussia and Austria, commonly called the Holly Alliance. It was the first of a series and was followed afterwards by other of a more marked and practical nature. These measures taken together, profess to establish two principles which the Allied Powers would introduce as a part of the law of the civilized world; and the establishment of which is to be enforced by a million and a half bayonets.

"The first of these principles is that all popular rights are held not otherwise than as grants from the crown. Society, upon this principle, has no rights of its own; its whole privilege is to receive the favors that may be dispensed by the sovereign power, and all its duty is described in the single word submission.

"The second, and, if possible, the still more objectionable principle, avowed in these papers, is the right of forcible interference in the affairs of other states. I want words to express my abhorrence of this abominable principle. An offence against one King is to be an offense against all Kings, and the power of all is to be put forth for the punishment of the offender. Sovereigns may go to war upon the subjects of another state to repress an example. And what, under the operation of such a rule, may be thought of our example. Why are we not as fair objects for the operation of the new principle, as any of those who may attempt a reform of government on the other side of the Atlantic?

"Is it not proper for us at all times, is it not our duty, at this time, to come forth, and deny and condemn these monstrous principles? Where, but here, and in one other place, are they likely to be resisted? They are advanced with equal coolness and boldness; and they are supported by immense power. The timid will shrink and give way, and many of the brave may be compelled to yield to force. Human liberty may yet, perhaps, be obliged to repose its principal hopes on the intelligence and vigor of the Anglo-Saxon race.

"It may now be required of me to show what interest we have in resisting this new system. What is it to us, it may be asked, upon what principles, or what pretences, the European governments assert a right of interfering in the affairs of their neighbors? The thunder, it may be said, rolls at a distance. The wide Atlantic is between us and danger; and, however others may suffer, we shall remain safe.

"I think it is a sufficient answer to this to say that we are one of the nations of the earth; that we have an interest, therefore, in the preservation of that system of national law and natural intercourse which has heretofore subsisted, so beneficially for all. Our system of government, it should be remembered, is, throughout, founded on principles utterly hostile to the new code; and if we remain undisturbed by its operation, we shall owe our security neither to our situation or our spirit. The enterprising character of the age, our own active, commercial spirit, the great increase which has taken place in the intercourse among civilized and commercial states, have necessarily connected us with other nations, and given us a high concern in the preservation of those salutary principles upon which that intercourse is founded. We have as clear an interest in international law, as individuals have in the laws of society.

"There is an important topic to which I have yet hardly alluded. I mean the rumored combination of the European Continental sovereigns against the newly established free states of South America. Whatever position this government may take on that subject, I trust it will be one which can be defended on known and acknowledged grounds of right. The near approach or the remote distance of danger may affect policy, but cannot change principle. The same reason that would authorize us to protest against unwarrantable combinations to interfere between Spain and her former colonies, would authorize us equally to protest, if the same combination were directed against the smallest state in Europe, although our duty to ourselves, our policy, and wisdom, might indicate very different courses as fit to be pursued by us in the two cases. We shall not, I trust, act upon the notion of dividing the world with the Holy Alliance, and complain of nothing done by them in their hemisphere if they will not interfere with ours.

"In the history of the year that has passed by us, and in the instance of unhappy Spain, we have seen the vanity of all triumphs in a cause which violates the general sense of justice of the civilized world. There is an enemy that still exists to check the glory of these triumphs. It follows the conqueror back to the very scenes of his ovations; it calls upon him to take notice that Europe, though silent is yet indignant. "I shall not, Mr. Chairman, attempt to recite the events of the Greek struggle up to the present time. Its origin may be found, doubtless, in that improved state of knowledge which, for some years, has been gradually taking place in that country. The emancipation of the Greeks has been a subject frequently discussed in modern times.

They themselves are represented as having a vivid remembrance of the distinction of their ancestors, not unmixed with an indignant feeling that civilized and Christian Europe should not ere now have aided them in breaking their intolerable fetters.

"The whole force of the Ottoman empire, at the commencement of 1822, was in a condition to be employed against the Greek rebellion; and, accordingly, very many anticipated the immediate destruction of the cause. The event, however, was ordered otherwise. Where the greatest effort was made, it was met and defeated. Entering the Morea with an army which seemed capable of bearing down all resistance, the Turks were nevertheless, defeated and driven back, and pursued beyond the isthmus, within which, from that time to the present, they have not been able to set their foot.

"The powerful monarchies in the neighborhood have denounced the Greek cause and admonished them to abandon it and submit to their fate. They have answered them, that, although two hundred thousand of their countrymen have offered up their lives, there yet remain lives to offer; and that is the determination of all, yes of all, to persevere until they shall have established their liberty, or until the power of their oppressors shall have relieved them from the burden of existence.

"It may now be asked, perhaps, whether the expression of our own sympathy, and that of the country, may do them good? I hope it may. It may give them courage and spirit, it may assure them of public regard, teach them that they are not wholly forgotten by the civilized world, and inspire them with constancy in the pursuit of their great end. At any rate, Sir, it appears to me that the measure which I have proposed is due to our own character, and called for by our own duty.

"I cannot imagine that this resolution might possibly provoke the Turkish government to acts of hostility. There is already the (President's) message, expressing the hope of success to the Greeks and disaster to the Turks, in a much stronger manner than is to be implied from the terms of this resolution. There is the correspondence between the Secretary of the State and the Greek Agent in London, already made public. I might add to this, the unexampled burst of feeling which this cause has called forth from all classes of society, and the notorious fact of pecuniary contributions made throughout the country for its aid and advancement.

"As little reason is there for fearing its consequences upon the conduct of the Allied Powers. They may, very naturally, dislike our sentiments upon the subject of the Greek revolution; but what those sentiments are they will much more explicitly learn in the President's message than in this resolution. They might, indeed, prefer that we should express no dissent from the doctrines which they have avowed, and the application which they have made of those doctrines to the case of Greece. But I trust we are not disposed to leave them in any doubt as to our sentiments upon these important subjects. We do no more than to maintain those established principles in which we have an interest in common with other nations, and to resist the introduction of new principles and new rules, calculated to destroy the relative independence of states, and particularly hostile to the whole fabric of our government.

"I close, then, Sir, with repeating, that the object of this resolution is to avail ourselves of the interesting occasion of the Greek revolution to make our protest against the doctrines of the Allied Powers; both as they are laid down in principle and as they are applied in practice. I think it right, too, Sir, not to be unseasonable in the expression of our regard, and, as far as that goes, in a manifestation of our sympathy with a long oppressed and now struggling people. The Greeks address the civilized world with a pathos not easy to be resisted. They stretch out their arms to the Christian communities of the earth, beseeching them, by a generous recollection of their ancestors, by the consideration of their desolated and ruined cities and villages, by their wives and children sold into an accursed slavery, by their blood, which they seem willing to pour out like water, by the common faith, and in the name, which unites all Christians, that they would extend to them at least some token of compassionate regard."

The importance of this speech was immediately recognized. It was called "the best sample of parliamentary eloquence and statesmanlike reasoning which our country can show." It was translated into every continental language and was read in every capitol and court of Europe. To the Greeks it was a most moving and sustaining encouragement. Webster himself was very proud of it. Years later when writing a friend concerning this Greek speech, he said, "I think I am more fond of this child than any of the family."

In December 1940 President Roosevelt sent a message to King George II of Greece. One paragraph is as follows:

"As your majesty knows, it is the settled policy of the United States Government to extend aid to those governments and peoples who defend themselves against aggression, I assure your majesty that steps are being taken to extend such aid to Greece which is defending itself so valiantly."

the clear dry air. At least, there was nothing like it at Carnival this year.

The latest reunion of our entire Class (one thing you can say for our Class, we always turn out a hundred per cent for our Reunions) was held during Outdoor Evening, at the bottom of a large puddle on Rope Ferry Road just beyond Sid Hayward's driveway. By using a sort of dogpaddle, and occasionally hopping up and down a little, we were able to keep our head above water until somebody set out from shore in a small boat and rescued us. Later that evening a haggard group of survivors, paddling back from the Golf Course on a makeshift raft fashioned of broken skis lashed together, reported that Billy Rose had been seen bidding spiritedly for the rights to next year's Carnival, to be used as the basis for his new Aquacade with Weismuller and Eleanor Holm.

Our companion in the puddle on Rope Ferry Road was Mr. F. W. Bronson of Yale, editor of the Alumni sheet at the New Haven institution, who came north to get his first impression of Hanover. Mr. Bronson's impression will be published later in a small volume entitled "Three Years Before the Mast; or, Through Dartmouth with Water Wings."

To be sure, as I tried to tell Bronson, Carnival isn't always like this. Back in the good old days of Our Own Class, for example, Carnival was very different indeed. For one thing, it was always held indoors, inasmuch as skiing and other snow-sports were still unknown. As far as we're concerned, they still are.

As a matter of fact, snow itself had not been invented when I went to school. I remember that a member of our Class named Tom Edison (or, as he was known when he was a boy, Mickey Rooney) was working at the time on an invention which he called "fnow," owing to the fact that the oldfashioned "s" looked like "f." This "fnow" resembled our modern snow in many ways, except that it was drawn by horses; but it was scoffed at by the college authorities of that day because it took so long to cut out each flake with a pair of embroidery scissors. It was not until years later that people realized the possibilities of Edison's invention. The modern Dartmouth Carnival is the result.

This lack of snow proved to be an advantage in several ways. For one thing, the snow-sculptures back in my time were not made of ice, but were posed by members of the fraternities themselves, who dressed up in white and stood on the lawns in front of the various houses, dressed as Eleazar Wheelock or King Winter, during the entire Carnival week-end. Naturally, if the weather were cold, the brothers would sometimes get quite stiff, a Carnival custom which I understand has not entirely disappeared.

Moreover, we never had the problem of what to do with our snow-sculptures after Carnival was over.

P.S.: It has just been brought to the attention of our Class Secretary that one Frank Sullivan of Cornell has been writing letters to the editor of this MAGAZINE, belittling the loyalty of our Class and impugning its motives. This would be the same Frank Sullivan who still owes us five dollars as a result of an ill-advised wager at the time of the Cornell game; and we can only put down his letter to a caddish resentment at being dunned for the money. To show our superiority to such attacks, we are willing to offer Sullivan herewith a freshman membership in our Class, provided he'll be willing to carry cigarettes and beat rugs and tip his hat to us on the campus. After all, a strong Class organization should start building right from the bottom; and we know of no better way of starting at the bottom than with Frank Sullivan.

The dues will be five dollars, please, Mr. S.

PROFESSORS MCCALLUM AND MORSE WILL SPEAK AT HANOVER HOLIDAY THIS JUNE Professor James Dow McCallum of the English Department will speak of the historicchanges in Dartmouth to the present day, and Professor Stearns Morse, also English Deparment, will speak on the "Prospects of Democracy" during the week following Commencement (June 16-21), climaxed by reunions of the 5-, 10-, 15- and 20-year classes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

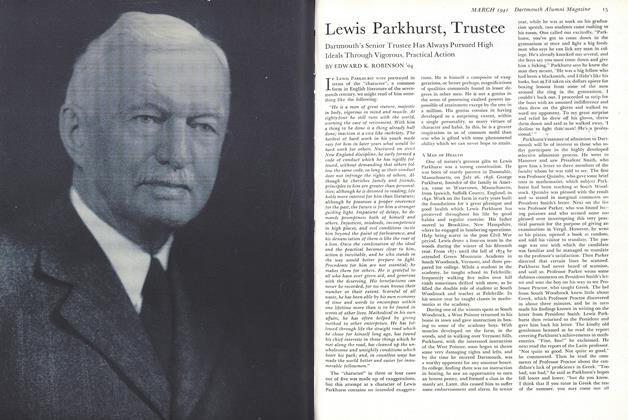

ArticleLewis Parkhurst, Trustee

March 1941 By Edward K.Robinson '04 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1941 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1941 By Charles Bolte '41. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

March 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. -

Article

ArticleA Generation Finding Itself

March 1941 -

Article

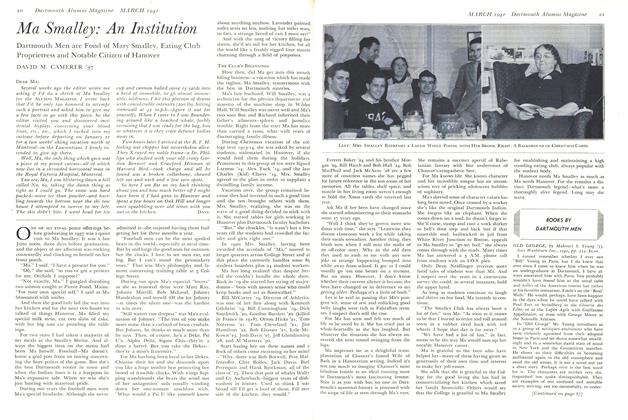

ArticleMa Smalley: An Institution

March 1941 By DAVID M. CAMERER '37, Dave.