The Transition from Undergraduate Life to the World Brings More Than Introspection: Self Discovery THOMAS W. BRADEN SECRETARY-CHAIRMAN, CLASS OF 1940

THERE IS NO PHRASE which is more annoying to the man just out of college than the one which goes, "process of adjustment, you know."

It is a phrase most often used by older alumni and whenever the subject of getting out of college is brought up by one of us who is doing so, the alumnus will bring it out and toss it lightly over the shoulder so to speak as though it settled the matter and on the subject of getting out of college there was nothing more to say.

Actually getting out of college involves the loss of friends, country, exercise, fellowship, sweatsocks, habits of thinking and something the sociologists call status, to say nothing of the clothes our roommates borrowed. Getting out of college is a malady in two phases, the gastric, which means standing outside the Bema and saying to a friend, "Well I'll see you in five years," and the cerebral, which means the introspective worrying peculiar to those who are homesick. It is an experience which is sad for some, a little terrifying for others, and difficult for everyone. And yet it is always referred to very casually as a "process of adjustment."

I do not mean to imply that the young men who graduated from Dartmouth last June are another lost generation, engaged in feeling sorry for themselves. I do mean that getting out of college is a job in itself —and quite enough for now.

I Sometime after graduation something happens to college boys which turns them into men. I think it is a sense of discovery.

Whether we would admit it or not, most of us who graduated from Dartmouth last June came out of college with a very definite idea that we were going to do something big to the world. The conception was partly adolescence, partly an exaggerated sense of our own self-importance, partly a class room training in Right and Wrong, in the devil and angel theory of society with a consequent vast ignorance about the importance of merely doing a job.

It is a peculiar method of learning—this sense of discovery. You would think we might have known that a job is a piece of interesting or dull routine which usually has very little to do with the large Right or the large Wrong. You would think we might have known that selling canned goods for example, is so remotely connected with Making Democracy Work that only a very expert advertising man can tie them up together on the same page of copy. You would think we might have known it, and probably we did, but there is some- thing about getting out of college and find- ing it out for yourself, something about making your own generalizations from your own experience which is a sharp and sometimes painful discovery.

There are some other discoveries and most of them we were warned about in the old aphorisms about small frogs, about college, from the standpoint of the many sidedness of living, being the Best Four Years, about College being easy, soft and undisciplined. But the most important discovery is the one which told us that sooner or later we must cease acting as though we had something we wanted to do with the world, and begin to find out what the world was willing to do with us.

It is a very important discovery to make, and most of us made it only after fighting it off—and sometimes losing a job. But we know now that if we develop a talent or skill and work at it hard enough then maybe somebody will be willing to use it, and fit us into the scheme for what we are worth. Since June we have succeeded in whittling ourselves down to size.

II Getting out of college in a time of war has been for most of us an experience in making up our minds and in discovering the things in which we believe.

There is supposed to be something wrong about this and about us for having had to go through the experience. College presidents, newspaper editors and the thinkpiece writers in the magazines have called us cowards, and wrong thinking, or have accused us of turning pro and becoming the youth with a capital Y.

The fact is of course that in matters of war and patriotism the Dartmouth man is as much of a cynic as any other college man. This is not the fault of our teachers or of our college. What makes us cynical is the fact of history, and no one man or institution can take the rap for that.

Unlike many of our professors who have hastened to deny and so obviously never believed what they taught us, the college product is perfectly willing to accept the facts about war which have made him cynical. He is not now saying that what Remarque said about what men look like draped over barbed wire is so much hokum. He is not trying to make himself believe that war is a glorious crusade, or that men never have made money out of others dying, or that the defeat of Germany will end war or spread democracy all over the world, or that there is not in the saga of men dying for ideals, a great deal of dirt, international politics and disillusionment.

These things were taught us by Hemingway and Millis and others and we accept them as facts. It is impossible for us to skirt them now by adopting some new and hastily prepared religion which men of little moral caliber have invented for the moment.

But if there is one difference between our generation and the one which got lost after the last war it is that we have been able to recognize the march of events, and from the hard, cynical factual background created for us by the experience of the last generation to come to the slow realization that if we are to maintain the things in which we believe, there is only one last resort, and that is fighting.

We shall not be fighting for nearly so much as we shall be fighting against. We will not go into this war with heads full of hokum, but with the recognition that all that another generation found out about war was very true, and that our generation, having gone beyond them, and found out something else, will fight and die not with disillusion but with the realization that that was the only thing left to do.

That isn't true of all of us. There are some of us who would in any time and any war follow the path of least resistence without thinking much about it. There are some of us unable to learn beyond the last war because they are too shallow and wellbred to learn anything from living. And certainly the process of discovering what we believe cannot be expressed in the one sided phrases of a newspaper editorial or an article on Youth. For us this has been a time of struggling with our convictions, of tying together our facts and our feelings, of tossing aside our prejudices, and recognizing our reservations, and coming face to face with the essence of our own beliefs.

It is true that we are cynics and the number of things we do not believe in is legion. It is true that we have a strong and healthy distrust for the fake and the insincere. But it is also true that most of us believe there is an actuality behind the old words which said that on this continent there is a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men shall have equal rights. Most of us would like to work to make that come true; most of us would kill or be killed to keep that idea from never having a chance to come true. And most of us have a strong faith that if after working or killing or being killed, this country we live in should have a new birth, it should be in freedom, and as usual, under some kind of God. That is about what we believe, and as a matter of fact, have all along. Only most of us never knew it before.

III Dartmouth is a kind of religion with most of the rites and some of the reaction which is part and parcel of all religions, and so coming back to Hanover, even after a short time away, is a sort of pilgrimage known to all alumni. For us, it has had a great deal to do with getting out.

As undergraduates most of us have watched the men of two or five or ten years out wandering aimlessly down Main Street, talking with members of the faculty or administration, or idling in a fraternity house or the Inn, thumbing through the pages of some old magazine. Sometimes we made the mistake of asking them what they were doing here and why, and nearly always we got some half embarrassed ansswer about just coming up and taking a look around.

Probably what they were doing was their own business, and different for all of them, depending upon what they'd been doing since they left, and how long they had been gone. But for those of us who are only six months out, coming back to Hanover is essentially, the same for all.

We walk across the campus or past a fraternity house and raise our arm to faces which should be there and aren't. We meet the underclassmen who formed a sort of inactive background for our four years, and find that after we have said, "How are you?" or "How are things going?" there is really not much more we have to say. And we walk into the office of the particular student organization to which we gave the most of our spare time and discover oddly that it seems to be getting along pretty well without us, and that the men who are working there now, though they are perfectly friendly and willing to gossip awhile, have a job to do which it would no longer be fitting for us to help them with, and really, if we stay much longer, we are going to be a little bit in the way.

There is some, but not very much consolation in reflecting that it was not very long ago we glanced across at the porch of the Hanover Inn, and wondered out loud what all those old guys were doing in town.

In a few years, looking back upon our first trip back to Hanover will probably be funny. Right now it is frankly a little sad. We have discovered that we are out of college, and that we can't go home again. From our standpoint this is important, and it is a good thing to find it out now.

Well, that is us. Nobody ever claimed that getting out of college is any fun, but it is just as valuable as getting in. We don't set ourselves apart, or ask anybody to be sorry for us because we are youth, and you would be surprised how little we worry about whose fault we are. We have discovered those three things at least, and we are trying to piece them together as well as we can, into the job of getting out of college.

Come to think of it, I guess you might call it a process of adjustment.

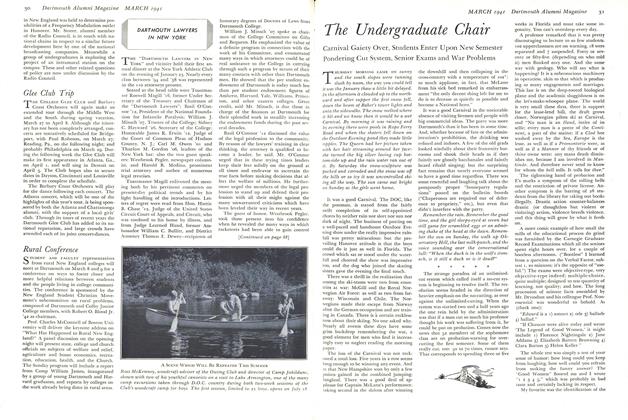

DARTMOUTH APPOINTS NEW TEACHERS TO POSTS IN DEPARTMENTS OF PHILOSOPHY AND MUSIC Left: Francis William, Gramlich, elected assistant professor of philosophy, was graduated from Princeton in 1933, and receivedhis M.A. and Ph.D. from the same institution. Right: William Raymond Kendall, new assistant professor of music, is a graduate ofOccidental College, has taught and studied at Whittier College and Stanford University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleLewis Parkhurst, Trustee

March 1941 By Edward K.Robinson '04 -

Article

ArticleGreece and Daniel Webster

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1941 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1941 By Charles Bolte '41. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

March 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. -

Article

ArticleMa Smalley: An Institution

March 1941 By DAVID M. CAMERER '37, Dave.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS TO HELP PICK NAMES FOR HALL OF FAME

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleLibrary Gifts

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleSenior Prizes

JULY 1959 -

Article

Article"Man of the Year" in St. Louis

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleForest Knowledge

January 1939 By Larry Lougee '29 -

Article

ArticleA CASE FOR THE CLASSICS

April 1933 By Richard J ackson '33