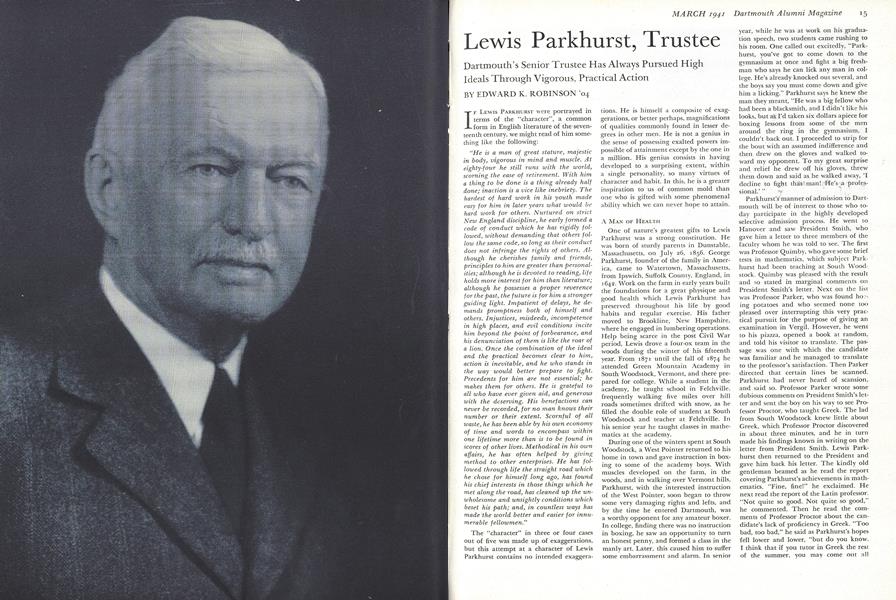

Dartmouth's Senior Trustee Has Always Pursued High Ideals Through Vigorous, Practical Action

IF LEWIS PARKHURST were portrayed in terms of the "character", a common form in English literature of the seventeenth century, we might read of him something like the following:

"He is a man of great stature, majesticin body, vigorous in mind and muscle. Ateighty-four he still runs with the world,scorning the ease of retirement. With hima thing to be done is a thing already halfdone; inaction is a vice like inebriety. Thehardest of hard work in his youth madeeasy for him in later years what would behard work for others. Nurtured on strictNew England discipline, he early formed acode of conduct which he has rigidly followed, without demanding that others follow the same code, so long as their conductdoes not infringe the rights of others. Although he cherishes family and friends,principles to him are greater than personalities; although he is devoted to reading, lifeholds more interest for him than literature;although he possesses a proper reverencefor the past, the future is for him a strongerguiding light. Impatient of delays, he demands promptness both of himself andothers. Injustices, misdeeds, incompetencein high places, and evil conditions incitehim beyond the point of forbearance, andhis denunciation of them is like the roar ofa lion. Once the combination of the idealand the practical becomes clear to him,action is inevitable, and he who stands inthe way would better prepare to fight.

Precedents for him are not essential; hemakes them for others. He is grateful toall who have ever given aid, and generouswith the deserving. His benefactions cannever be recorded, for no man knows theirnumber or their extent. Scornful of allwaste, he has been able by his own economyof time and words to encompass withinone lifetime more than is to be found inscores of other lives. Methodical in his ownaffairs, he has often helped by givingmethod to other enterprises. He has followed through life the straight road whichhe chose for himself long ago, has foundhis chief interests in those things which hemet along the road, has cleaned up the unwholesome and unsightly conditions whichbeset his path; and, in countless ways hasmade 'the world better and easier for innumerable fellowmen."

The "character" in three or four cases out of five was made up of exaggerations, but this attempt at a character of Lewis Parkhurst contains no intended exaggerations. He is himself a composite of exaggerations, or better perhaps, magnifications of qualities commonly found in lesser degrees in other men. He is not a genius in the sense of possessing exalted powers impossible of attainment except by the one in a million. His genius consists in having developed to a surprising extent, within a single personality, so many virtues of character and habit. In this, he is a greater inspiration to us of common mold than one who is gifted with some phenomenal ability which we can never hope to attain.

A MAN OF HEALTH

One of nature's greatest gifts to Lewis Parkhurst was a strong constitution. He was born of sturdy parents in Dunstable, Massachusetts, on July 26, 1856. George Parkhurst, founder of the family in America, came to Watertown, Massachusetts, from Ipswich, Suffolk County, England, in ) 642. Work on the farm in early years built the foundations for a great physique and good health which Lewis Parkhurst has preserved throughout his life by good habits and regular exercise. His father moved to Brookline, New Hampshire, where he engaged in lumbering operations.

Help being scarce in the post Civil War period, Lewis drove a four-ox team in the woods during the winter of his fifteenth year. From 1871 until the fall of 1874 he attended Green Mountain Academy in South Woodstock, Vermont, and there prepared for college. While a student in the academy, he taught school in Felchville. frequently walking five miles over hill roads sometimes drifted with snow, as he filled the double role of student at South Woodstock and teacher at Felchville. In his senior year he taught classes in mathematics at the academy.

During one of the winters spent at South Woodstock, a West Pointer returned to his home in town and gave instruction in boxing to some of the academy boys. With muscles developed on the farm, in the woods, and in walking over Vermont hills, Parkhurst, with the interested instruction of the West Pointer, soon began to throw some very damaging rights and lefts, and by the time he entered Dartmouth, was a worthy opponent for any amateur boxer. In college, finding there was no instruction in boxing, he saw an opportunity to turn an honest penny, and formed a class in the manly art. Later, this caused him to suffer some embarrassment and alarm. In senior year, while he was at work on his graduation speech, two students came rushing to his room. One called out excitedly, "Parkhurst, you've got to come down to the gymnasium at once and fight a big freshman who says he can lick any man in college. He's already knocked out several, and the boys say you must come down and give him a licking." Parkhurst says he knew the man they meant, "He was a big fellow who had been a blacksmith, and I didn't like his looks, but ais I'd taken six dollars apiece for boxing lessons from some of the men around the ring in the gymnasium, I couldn't back out. I proceeded to strip for the bout with an assumed indifference and then drew on the gloves and walked toward my opponent. To my great surprise and relief he drew off his gloves, threw them down and said as he walked away, 'I decline to fight that" man! He's a professional.'"

Parkhurst's manner of admission to Dartmouth will be of interest to those who today participate in the highly developed selective admission process. He went to Hanover and saw President Smith, who gave him a letter to three members of the faculty whom he was told to see. The first was Professor Quimby, who gave some brief tests in mathematics, which subject Parkhurst had been teaching at South Woodstock. Quimby was pleased with the result and so stated in marginal comments on President Smith's letter. Next on the list was Professor Parker, who was found homing potatoes and who seemed none too pleased over interrupting this very practical pursuit for the purpose of giving an examination in Vergil. However, he went to his piazza, opened a book at random, and told his visitor to translate. The passage was one with which the candidate was familiar and he managed to translate to the professor's satisfaction. Then Parker directed that certain lines be scanned.

Parkhurst had never heard of scansion, and said so. Professor Parker wrote some dubious comments on President Smith's letter and sent the boy on his way to see Professor Proctor, who taught Greek. The lad from South Woodstock knew little about Greek, which Professor Proctor discovered in about three minutes, and he in turn made his findings known in writing on the letter from President Smith. Lewis Parkhurst then returned to the President and gave him back his letter. The kindly old gentleman beamed as he read the report covering Parkhurst's achievements in mathematics. "Fine, fine!" he exclaimed. He next read the report of the Latin professor. "Not quite so good. Not quite so good," he commented. Then he read the comments of Professor Proctor about the candidate's lack of proficiency in Greek. "Too bad, too bad," he said as Parkhurst's hopes fell lower and lower, "but do you know, I think that if you tutor in Greek the rest of the summer, you may come out nil right." And thus did Asa D. Smith, in serving as a predecessor to Bob Strong in the capacity of admissions officer, save for Dartmouth a student whose loss to the institution would have been no small calamity.

Bound volumes of the Aegis of Mr. Parkhurst's time, indicate that he was enrolled among the members of the class of 1878 as an "Academical Student"; that he registered from Dunstable, Massachusetts, and that he roomed at Mr. Russell's. (The word "Academical" is replaced by "Academic" a year or two later.) There were seventy-five men in his class and a total of two hundred sixty-seven "academical" students in the College. The scientific students numbered seventy-seven, medical students seventy-eight, Thayer School four, and agricultural students thirty-three, making a total of four hundred fifty-nine listed in the General College Catalogue.

The faculty numbered thirty-five, quite a respectable ratio of instructors to students for those days. Among the faculty members who were still teaching in the early years of this century were C. H. Hitchcock, Robert Fletcher, C. F. Emerson, John K. Lord, Frank A. Sherman, and T. W. D. Worthen.

The College buildings then were Dartmouth Hall, Wentworth, Thornton, Reed, Conant, Bissell, South, Culver, the Observatory, and the Medical Building. The combined College libraries contained 51,820 volumes and new ones were being added at the rate of about one thousand annually. Daily and weekly papers from all large New England cities and New York were available in the College reading room, as well as numerous religious, scientific, and literary magazines.

Musical organizations included the Handel Society, made up of fourteen male voices, the Glee Club, then only a double quartette, and the College orchestra, of four instruments. Thirteen concerts were given by the musical clubs in different places in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts during the year. There were two literary societies, the Social Friends and the United Fraternity. Obviously the cultural life of the College even in those days offered more than the average student could absorb.

Among the athletic organizations the Dartmouth Boat Club came first. It was then engaged in intercollegiate competition. At the Saratoga meet the Dartmouth "University" crew of 1875 came in fourth, following Cornell, Columbia, and Harvard, ahead of Wesleyan, Yale, Amherst, Brown, Princeton and four other contestants. This crew was known as the Dartmouth Giants but the recorded height and weight of the members falls conspicuously below that of the big men on the Dartmouth teams of today; further evidence that the race is growing larger. The average age was twenty-two and one half years, the average height six feet, and the average weight one hundred sixty-six. Parkhurst was captain of the '78 class crew that year and later became a member of the university crew. A "college nine" represented Dartmouth in baseball and each class had its own team.

For entertainment there existed a Chess Club, a Shakespearean Club, several whist clubs, and three "telegraph companies", which we may suppose would have included the radio hams of today. Parkhurst appears to have been a member of one of these companies. Among the "Facetiae" listed in the frivolous pages of the Aegis were the Thornton Hall Squakette, the Knights of the Pasteboard, the Famous Mulligan Guard, the Quechee Trio, the Seekers after Forbidden Fruit, and the Grand Order of Haymakers. "Odds and Ends", a department of the Aegis, reveals that the first ringing of the College bell occurred at six A.M.; that the youngest student was fifteen years of age, the oldest, fifty; that "no health statistics have been kept, the purity and bracing quality of the air, together with the general participation in outdoor sports, tending to produce unexampled freedom from illness"; that for yearly expenses, $275 would suffice for the very economical student; the average student requiring $400, these estimates being exclusive of vacations.

With Shattuck '78, Lewis Parkhurst during freshman year roomed at D. B. Russell's house. He recalls that the room rent was $15 per semester. The bedroom was nothing more than an overgrown closet, without windows, in which stood a bed, presenting to view only interwoven ropes instead of mattress and spring. A large baglike piece of cloth lay on the ropes. "Take that ticking out to the barn", said Mr. Russell, "and fill it with oat straw. That'll make a good bed for you." And it did serve until later when Shattuck's mother sent the boys a feather bed from Woodstock. One reason why he chose Russell's house his freshman year, Mr. Parkhurst says, was that it offered him an opportunity to do his own washing and hang it on the roof where it could not be seen.

Parkhurst, like most good business men, has always believed in discounting his bills. A classmate appeared at the beginning of freshman year, and offered a tempting discount on the cost of board if paid in advance. Parkhurst scraped together enough to make the payment, and got the discount. That was about all he got, however, for the amount of food forthcoming in this big business deal was only enough to keep him from starving to death.

The beginning of Dartmouth track athletics occurred in Parkhurst's undergraduate years. In freshman year a field day was held, a band from Union Village or some other near-by town was employed, and track sports were organized informally and run off on the campus in picnic fashion. Parkhurst entered and won the threemile walk. The next year the track meet became a more formal affair and the records show that Parkhurst won the threemile walk in 29 minutes, seconds. At the spring meet on May 31 and June 1, 1876, he lowered this time to 28 minutes, 43 seconds, in winning the event, but the best he could do in the one-mile walk was to take second place.*

Soon after, a classmate invited Parkhurst to spend some time with him at his home in Springfield, Vermont, where there was a barber who had trained with Weston, a former national champion who retained his walking crown for many years. This barber walked with Parkhurst, showed him the fine points of the old square heel-and-toe walk, and lengthened his stride four inches. Thereafter, Parkhurst was not defeated in any of the college track meets, and the three-mile record he established, 25 minutes, 16 2/3 seconds, was never broken. It is recorded on the walls of the gymnasium as the best record ever made by a Dartmouth undergraduate in this event.

WAS HIS OWN COACH

There was no Harry Hillman in those days to watch faithfully over the track performers. The coaching and training each man received was what he provided for himself, or nothing. Parkhurst had a certain distance carefully marked off on one of the roads near town, and early on many mornings downed a glass of cider with a raw egg, and seriously square-toed and heeled it over the measured course.

In his sophomore year and until graduation, a room at "Mr. Blaisdell's" on Lebanon Street was Parkhurst's domicile in Hanover. He joined Delta Kappa Epsilon, and was president of his class the second term of freshman year, both terms of sophomore year, and the first term of senior year.

He would display righteous Republican wrath at being called the original thirdtermer, but such appears to be the case from an examination of the records. Furthermore, he seemed to be a kind of permanent football captain for his class according to the testimony of his class secretary, W. D. Parkinson, given in "Narrative of a Half Century and Somewhat More", a full report of the class published in 1932. A copy is in the College library, and for those interested in Dartmouth life in the seventies, it provides an abundance of rich material. Records of service in numerous other offices and on various committees prove that in undergraduate life as in later years, Parkhurst was a leader in good works and was well esteemed by his fellows.

Although an examination of the records reveals no evidence that he won any prizes in scholarship or was elected to Phi Beta Kappa (he was, however, elected to Phi Beta Kappa a few years ago, much to his surprise), his classroom performances must have been more than adequate, for he succeeded during his course in getting some of the best teaching positions available for Dartmouth students. Undoubtedly, scholarship suffered because he devoted so much time to the effort of earning his way. TheDartmouth of June 13, 1878, included the following under "TEACHING" in the statistics of the class of '78: "Lewis Parkhurst leads those who have completed their course in four years, he having taught sixty weeks." Imagine having to make up fifteen weeks of lost recitations each year!

Parkhurst taught in Weston, Vermont, (whence came Mrs. Parkhurst!) during his freshman year, and in Provincetown, Massachusetts, during his sophomore year. This was the highest paid teaching job filled by the Dartmouth students, and also the toughest. The class was made up of about fifty boys, of various races and colors, from fourteen to twenty-one, many of whom went whaling in the spring and summer months. Their heart's desire was to lick the teacher. In the case of L. P., they never did. And if any of them happen to be living and want to try again, I'd put my money on the teacher! In his junior year Parkhurst taught the village school in Hanover, the first man ever employed for that work. Of his record there let The Dartmouth of March 21, 1878, tell the story: "It is now two years since Lewis Parkhurst '78, assumed control of the village school. Since that time the school has continually advanced in scholarship, and in the estimation of the townspeople, so that at the beginning of the winter term just completed, Mr. Parkhurst was engaged at a higher price than he was paid the year before. As he will graduate in June and be obliged to look for employment that will keep him busy all the time, it is proposed to hire him by the year at a salary of $1.000 Whether the plan is carried out or not, the proceedings show in how high estimation Mr. Parkhurst is held by the parents of the district, which does not fall to the lot of every teacher."

The most cherished volume in Mr. Parkhurst's library, he will tell you, is a copy of Webster's Unabridged Dictionary with this inscription on the end-leaf:

"Presented to Lewis Parkhurst by his grateful Pupils in District No. 1, Hanover, N. H. as a token of their respect and love.

Hanover, N. H. March 8, 1878."

N. A. Frost, long-time jeweler in Hanover, was so much pleased with Parkhurst's work as a teacher in Hanover that he lent the money Parkhurst needed to complete his college course.

Evidently Hanover District No. I failed to hold him as its teacher, for his first and second years after graduation were spent as principal of the High Street Grammar School in Fitchburg, Massachusetts. The money Frost had lent him was used up for Hanover expenses, and Deacon Downing lent him 150 to get to Fitchburg and pay expenses until he received his first pay check. These two Hanover worthies were repaid many years ago, and we assume they have collected also whatever additional rewards the recording angel may have seen fit to pass out to them for these and many other good deeds they performed here on earth, but warm gratitude for their generous kindness to him still glows in the heart of Lewis Parkhurst.

MOVE TO WINCHESTER

After two years of teaching in Fitchburg, came one year as principal of the Athol, Massachusetts High School, followed by five years in the same capacity in Winchester, Massachusetts, where Mr. and Mrs. Parkhurst have made their home ever since.

Edwin Ginn, a Winchester resident, having been impressed with the work and personality of Lewis Parkhurst, induced him to join the sales force of Ginn and Company, then a young and growing firm of textbook publishers. Mr. Parkhurst's first activities for Ginn and Company were in the sales department. He became the high school and college representative of the firm for New England on January 1, 1887, and was so outstandingly successful that he was admitted to partnership in 1889. His initiative and vision became evident from the very first, for the records of the company show, that it was at his suggestion in 1887 that a separate editorial department was established. Justin H. Smith, Dartmouth '77, who two years before had joined Ginn and Company's New York branch, was then made co-editor with Edwin Ginn. Mr. Smith's career with the firm was a distinguished one, although comparatively brief. He later endowed a chair in history at Dartmouth, became a member of the faculty for several years, and wrote a number of notable volumes in history. Of one of these, "The Mexican War", the Neiv York Sun said, "It need never be done again."

Soon after Mr. Parkhurst became a partner, Mr. Ginn became increasingly interested in having his company make all the books which they published, and more and more the various processes of manufacture were brought under the control of the firm. In 1896 a site on the Charles River, in Cambridge, was selected for a new plant, which on completion was named the Athenaeum Press, and the work of supervising and planning its construction was given to Mr. Parkhurst. Later, he had the pleasure of making several substantial additions, which increased the daily production capacity of the press in case of necessity to 40,000 complete volumes.

It was but a short time after his employment by Mr. Ginn before Lewis Parkhurst rose high in the councils of Ginn and Company. His innate good business judgment, his keen discernment of the real fundamentals in any problem, combined with his high ideals, made him an invaluable co-worker for Edwin Ginn, whose ideals and visions, although essential to the building of a great enterprise, sometimes grew to almost impractical bounds and needed the balanced judgment of Parkhurst to hold them within workable limits. Mr. Ginn respected the ability and soundness of his younger partner and placed great dependence on him. After Mr. Ginn's death, in 1916, Mr. Parkhurst continued to be a great influence for strength in the days of the company's greatest growth, through the twenties, until it became one of the largest enterprises in the history of publishing.

Mr. Parkhurst's retirement from Ginn and Company in 1933 at the age of seventy-seven closed forty-six active and fruitful years with the firm. In addition to being treasurer, he was in charge of all manufacturing during most of these years.

As a citizen of Winchester, Mr. Parkhurst's services and benefactions have been so extensive that a complete recital of them would require many pages. He has served as a member of almost innumerable committees and has been chairman of many of them. He has a fondness for building and has been a member of the committees which built the Unitarian Church and two of the school buildings in town. He gave an organ to the Unitarian Church. He gave a library to the High School. He worked enthusiastically for a suitable War Memorial, which project, as any Winchester citizen could relate, dragged through seven years of vicissitudes and several committees, as such things sometimes do in the very best of towns. Finally, when the smoke cleared away, Winchester found itself in possession of a very beautiful piece of memorial statuary by Herbert Adams. Of the large cost of this, Lewis Parkhurst personally had contributed about four-fifths.

Winchester is one of Boston's most beautiful suburbs. It lies in the Mystic Valley, through a part of which flows the Aberjona River. Wooded hillsides shelter many beautiful homes, from which can be seen the lovely Mystic Lakes. As in most New England towns, the early settlers in Winchester were compelled to give first attention to things utilitarian. They had little time for the aesthetic side of life. Tanneries and mills were built along the shores of the Aberjona. Livery stables appeared. Shacks of one sort and another were built on the low land bordering the river. In time, as these buildings outwore their usefulness, the land surrounding them became a dumping ground for sewage, tannery waste, or anything else anyone wanted to throw away, the unsightliness and health menace became greater and greater. Many in Winchester wanted to clean up, but this was not easy, for there were the matters of power rights, flowage, and kindred things, which complicated the problem and made the cost seem almost prohibitive.

WINCHESTER CLEAN-UP CAMPAIGN

Working with Forest C. Manchester, a leader in Winchester affairs at the time, Mr. Parkhurst made the first efforts to clean up the center of the town along the Aberjona. The owner of the largest piece of property involved was a Mr. Whitney, and to him flowage and power rights seemed worth much more than the town could afford to pay. Endless negotiations were carried on, one obstacle after another was surmounted, various state and county commissions were satisfied, and Mr. Whitney, after a period in which Mr. Parkhurst called on him for twelve successive days, signed an option. He later said that no one else ever could have made him sign, but "Parkhurst was always pleasant and patient and at last I just had to."

This was the beginning of the rehabilitation of the Aberjona. A freight yard, tannery, livery stable, and other structures were removed, the ground was leveled off and planted, and named Manchester Field, a play area for the young people of the town. Much was still to be desired of the old Aberjona, however. Long stretches of shore were still pestilential spots ideal for mosquito breeding. Stagnant pools abounded in neighboring marshes. Mr. Parkhurst resumed his efforts to have the town eliminate the ugly places and danger spots, so that only "water and green grass would meet the eye." He was ridiculed in town meeting and told that the expense of what he proposed would run into millions. Now, unless a person wishes to incite Lewis Parkhurst to redouble his efforts, it is not a wise move to ridicule him. In this case, he proceeded quietly to buy one after another of the properties along the stretch of river he then wished to have improved, until he had acquired them all. He then had the river bed dredged, and filled in the swampy border lands. An expert helped in the landscaping, and the whole project, completed at a cost of only $23,000, was turned over to the town with Mr. Parkhurst's compliments as a demonstration of what could be done at a reasonable cost. Since then the town has continued the improvement and beautification of the river and the valley lands which border it, and those who know the story are everlastingly grateful to Lewis Parkhurst for his foresight, his determination, and his generosity, which as one citizen wrote, resulted in bringing to completion a set of plans which "will complete a park system making Winchester more beautiful than any of us ever expected it could be."

The Massachusetts Horticultural Society presented to the officials of the town an illuminated scroll, in which this statement is contained:

"In recognition of excellent judgment and rare good taste made manifest by town officials in the plan of the public parks, and in the beautification of its highways, Winchester has become outstanding among the Commonwealth's many beautiful communities."

This is the first time that this Society has officially given any town such a scroll.

In his services to the state of Massachusetts, Mr. Parkhurst has shown no less enthusiasm for what he has believed best and right than he has in his activities for his town. In 1908 he was elected to the Massachusetts General Court from his district. He served on the joint Senate and House Committee on Railroads. At the end of his term one of the Boston papers said, "None will be missed next year more than Representative Lewis Parkhurst of Winchester, one of the most valued members of the Committeeon Railroads Althoughhaving served but one year, Representative Parkhurst will not come back, declining a renomination. He consented to stand last year only after prolonged urging, and he has been obliged to sacrifice his business." Another paper said, "Mr. Parkhurst of Winchester is a new member who has risen to distinction. He has been on the railroad committee and has spoken but little. Yet at the end of the session, he stands forth one of the best speakers of the House, both in force and logic."

In 1917-1918 Mr. Parkhurst served as President of the Republican Club of Massachusetts.

In 1921-1922 he was a member of the State Senate, in which he took his seat just eighty years after his grandfather, Henry Parkhurst, had entered the Senate as a member from Dunstable.

During his term as Senator a report on conditions in the old Charlestown State Prison, built in 1805, which forty years before had been condemned as unsuitable for modern use, attracted Mr. Parkhurst's attention. He introduced a bill for a new prison, which was defeated. He continued his efforts through the remainder of his term, and thereafter by written articles, large paid advertisements in newspapers throughout the state, and by personal addresses, until the sentiment throughout the community was largely with him. Commissioner of Correction Bates supported his campaign.

An excellent example of Mr. Parkhurst's incisive and logical style is to be found in the literature on the State Prison campaign. It is doubtful if Mr. Parkhurst ever wrote or spoke a sentence of which the meaning was not clear. Directness and simplicity were as effective in his speech as in his thinking. Concerning a new prison he wrote:

"Can the State of Massachusetts longer afford to use nearly ten acres of land in Charlestown—in the midst of the business and transportation section of the city, valued at one dollar per square foot by the assessors of Boston—when it owns about a thousand acres of land in Norfolk, worth, unimproved, not more than $15.00 an acre?

"Can it afford longer to pay the overhead charges of four state institutions, at Charlestown, Concord, Rutland, and Norfolk, when two would be sufficient?

"Can it afford to use a prison with buildings so crowded inside the walls, and with buildings and freight cars so near outside the walls that in order to be reasonably safe nine men are required to man the walls at Charlestown whenever the inmates are out of their cells, while four can give a greater measure of safety at Norfolk?

"Can it afford longer to pay 28.9 cents per day for food at Charlestown while it costs only 13.6 cents per day at Concord (See annual report of Commissioner of Correction for the year 1931, page 154)? There is no reason why the expense for food at Norfolk, when the plant is properly equipped and the farm lands developed, need be any greater than at Concord."

Not only was the Parkhurst Prison Bill defeated while he was a member of the legislature, but it failed to pass when presented for four successive years thereafter. But temporary defeats never knocked out Lewis Parkhurst. He had the great satisfaction in 1927 of seeing the legislature make an appropriation for $100,000 for the beginning of a new prison colony at Norfolk. The work was continued from year to year, very much along the lines advocated by Mr. Parkhurst after studies made by him in many states, and in a few years' time Norfolk was developed into one of the best modern penal institutions in the country.

His interest in this project has been sustained until the present time, and has been manifested in various ways, one of which is the fine library he gave for the prisoners. It included all the books recommended by a professional librarian, with special regard for the interest and education of the potential readers. The library was completely catalogued and classified, and its listing and index required thirty-four pages of printed text. The gratitude of the prisoners led them to raise contributions among themselves for a portrait of Mr. Parkhurst. This was hung in the library, much to the surprise of Mr. Parkhurst when he first viewed it. In a contribution to a periodical issued by the state's prisoners, one of them wrote:

"It is to the Senator, therefore, that we owe our library, its fine facilities, and many of the new books that constantly replenished it. And this is not all we owe him. He has given us an even richer gift—his confidence. And this confidence makes us feel that he has accepted us not for what we were, but for what we are and what we may become with a little encouragement. We also feel that our one steadfast friend is intent not upon our faults but upon our efforts to correct them, and hence the books."

This is one of the numerous heartfelt statements which have been made by prisoners in appreciation of Mr. Parkhurst's gifts. At one time, he stated, "Probably for what I have put into that prison in the way of work and money, perhaps a larger return has come to me than from anything else that I have ever done."

An intense love for his Alma Mater has long been a trait of the Dartmouth alumnus. Few are able to materialize this devotion to any conspicuous extent and to supplement it with years of service. Lewis Parkhurst has done both. Although of necessity his greatest energies have been andevoted to Ginn and Company, Dartmouth has been the constant beneficiary of his talents and his donations for many years. In 1908 he was elected an Alumni Trustee of the College. In 1913 he was honored with another term, and in 1915 was made a Life Trustee. His selection for service as Trustee tee was a careful and deliberate one. President Tucker and others wished at that time to add to the Board a man with imagination and courage, who also could provide the kind of systematic constructiveness which Mr. Parkhurst had so fully demonstrated in his career with Ginn and Company. It was not long after his election to the Board before Mr. Parkhurst established a careful system of budgeting and brought about a planned orderliness in the financial affairs of the institution. He and others since then have efficiently expanded and reorganized the methods of business administration of the College to meet its enlarged needs.

No better characterization of Mr. Parkhurst's services to Dartmouth can be written than that of President Hopkins in 1928, when conferring on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws:

"For two decades vital contributor tothe strength of Dartmouth's governingboard and wise collaborator with three administrations; deviser of the Collegebudget system and conservator of its financial affairs; generous donor, commemorating here the life and character of a belovedson; first among the Trustees insistent inemphasizing the need of a new Library andfrom the beginning active cooperator in allplans to this great end; whose interest inand participation in public affairs of yourstate have been associated with keen senseof responsibility for the welfare of yourhome community; practical student ofpenology, I confer upon you the honorarydegree of Doctor of Laws."

Recently the President has also said of Mr. Parkhurst:

"Over a period of many years the College has been indebted to Mr. Parkhurstfor his spirit of cooperation and his selfsacrificingloyalty in any matter which hadto do with College affairs. Financially, hehas been a far more generous contributorthan appears in any public record. Forinstance, throughout the period since hisfar-sightedness saw the desirability of having administrative offices centralized in asingle building and provided the funds forsuch a building, he has insisted on providing for its maintenance, both in the overhead of its upkeep and in the very considerable and expensive remodelings of thebuilding from time to time to give increased space. Always his advice and counsel have been available to any College officer when these could be given to himhelpfully and always he has been not onlythe official supporter but the personalfriend and confident of the three presidents with whom he has been associated."Whether personally or officially, Icould not overstate my own sense of obligation to him for the generous help which hehas made available to me at any time andunder any circumstances, and this I knowwould have been the testimony of Dr.Nichols or Dr. Tucker."

Most Dartmouth alumni will understand the above reference to the administrative offices of the college. In 1912 Mr. and Mrs. Parkhurst gave to the College the building which bears their name, in memory of their son, Wilder, who died at the beginning of his sophomore year in Hanover. His freshman record had been a brilliant one. He had led his class in both mathematics and Greek. The inscription of the donors on a bronze tablet in Parkhurst Hall beautifully commemorates the gift:

L. P. W. L. P. 1878 1907 TO WILDER LEWIS PARK HURST WHO DURING A SINGLE YEAR OF COLLEGE LIFE REALIZED HIS HIGH IDEALS OF LEARNING FRIENDSHIP DUTY AND ATTAINED THE GOAL OF HIS AMBITION TO BE A WORTHY MEMBER OF HIS FATHERS COLLEGE MAY THIS BUILDING STAND AN ENDURING MEMORIAL OFFERED FOR THE SERVICE HE MIGHT HAVE RENDERED THE COLLEGE WHICH GAVE OF ITS BEST TO FATHER AND SON 1911

Richard Parkhurst, another son, was graduated from Dartmouth in 1916. He then entered the employ of Ginn and Company, demonstrating such competence and administrative ability that he was soon made assistant manager of the Athenaeum Press, a position he very successfully filled for several years. His health, however, finally required a prolonged absence in the West, after which he returned to Winchester. Soon after, he became one of the Commissioners of the Port of Boston. He has met with marked success in advancing the interests of Boston as a seaport and is still continuing this work. He married Catherine Ryder, a daughter of H. D. Ryder of the Class of 1876. They have three children, John Wilder, 16; Margaret, 11; and Stephen Ryder, 10. To say that Lewis Parkhurst esteems his grandchildren no less than he does Dartmouth is no belittlement of the College.

Although the Administration Building undoubtedly represents Mr. Parkhurst's greatest benefaction to Dartmouth, he has said in the past that a contribution of which few ever heard was his greatest service to the College. When a young agent for Ginn and Company, he visited Hanover for the purpose of persuading some of the professors to use Ginn books. Professor Parker told him he would find many of the faculty in attendance at a meeting that evening to consider the establishment of a new system of waterworks for the town. Professor Arthur Sherburne Hardy, an engineer with West Point training, advocated the damming of Mink Brook, and the pumping of water to the height required to supply the village. All other plans that were submitted also required the use of power. Professor Parker asked Lewis Parkhurst to tell the meeting how Winchester managed its water supply. Parkhurst told how pasture land had been cleaned off and fenced in, a dam constructed, and the resulting reservoir filled with water from springs and rainfall. Gravity was the only power used. Professor Hardy ridiculed the idea. Ridicule has always stimulated Mr. Parkhurst, and he went into action at once. He urged the town to send a representative to Winchester as his guest. This was done, with findings so favorable, both in the practical demonstration and in the conference with the Winchester engineers, that the same system was adopted in Hanover, and with enlargements, has ever since been used to supply the town with water.

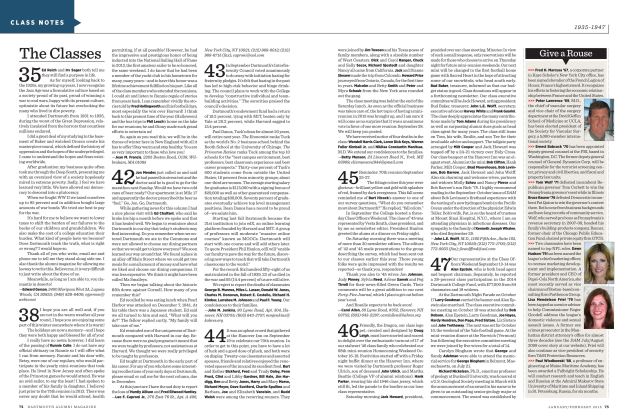

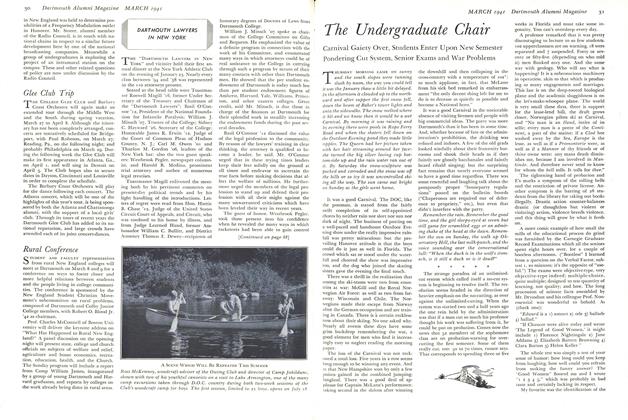

When teaching in the winters of 1874 and 1875 in Weston, Vermont, Mr. Parkhurst became acquainted with one of the other young teachers in town, Emma J. Wilder. Evidently the two were congenial, for Parkhurst invited Miss Wilder to attend his graduation in 1878 Sixty years later the secretary of '78 said in his report of his class reunion, "Parkhurst was accompanied by the same girl who was his guest at graduation, and he and she were our host and hostess at the Inn." This "girl" has now accompanied Parkhurst through sixty years of married life and has shared many of his benefactions and good deeds.

The little town of Weston, Vermont, has benefited greatly because once a young student at Dartmouth taught there to earn money for his college expenses. It has re- ceived for a Community Club an old tav- ern which was restored by the Parkhursts and one of their relatives. Its old cemetery has been renovated and replanted. The brook running through the center of the town has had its banks cleared of dilapidated buildings and has been made a thing of scenic beauty. A library building has been provided, together with annual contributions for maintenance and for the purchase of books. An old church has been rescued, just as it was about to be rebuilt into tenements; its historic pews and stained glass windows have been preserved, and the edifice is rented at $1.00 per year by Mrs. Parkhurst to the community church society of Weston. A parsonage has been provided. A playground next to the school has been donated for the use of the pupils and young people of the town.

pupils aim young people of the town. The benefactions of these good people seem to be endless. And they are the more meritorious, for the Parkhursts' means, although ample, are not measured in terms of great wealth. They have preferred to share their good fortune with others, rather than to lay up for themselves great treasures on earth. And now, in the richness of their years, in their home on Oak Knoll, overlooking much of the town they have so greatly benefited, with children, grandchildren, and many friends living near their little hill, they may if they choose to listen, hear a voice which says, "Well done!"

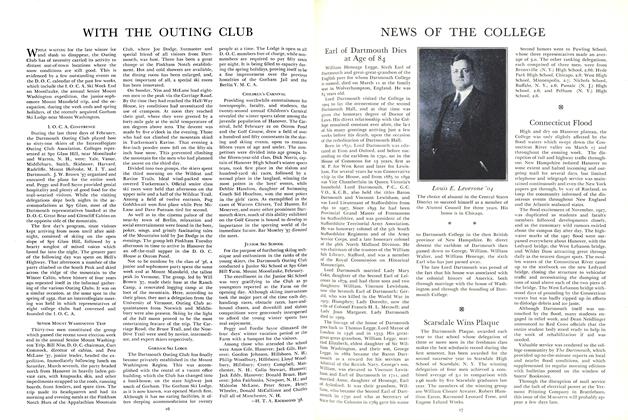

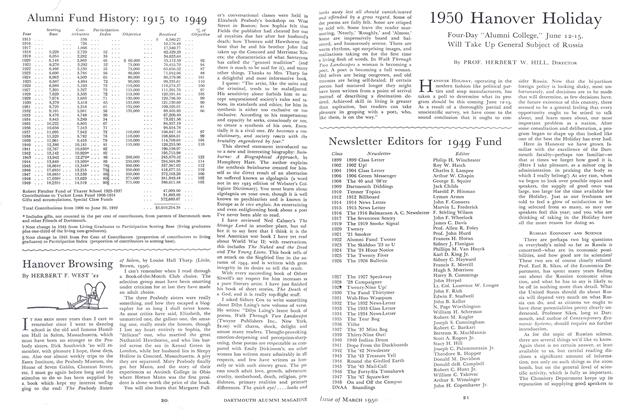

ATHLETES OF THE CLASS OF 1878 Parkhurst, the champion walker, stands resplendent on the left in a suit lent by a Springfield, Vermotit barber. Others in the group standing left to right: Gove, Gerould, Dana,Templeton, Pettibone, Rice. Seated: Cloud, Vittum, Hayt, Caverly. Reclining: Paul.

THE WINCHESTER WAR MEMORIAL, LARGELY THE GIFT OF LEWIS PARKHURST

MR. AND MRS. PARKHURSTThis photograph was taken on the occasion of their sixtieth wedding anniversary.

* The records given here are not exactly the same as those recorded in the gymnasium. These are taken from volumes of the Aegis published at the time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGreece and Daniel Webster

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

March 1941 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1941 By Charles Bolte '41. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

March 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. -

Article

ArticleA Generation Finding Itself

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleMa Smalley: An Institution

March 1941 By DAVID M. CAMERER '37, Dave.