LAWYERS AND THE CONSTITUTION: HOW LAISSEZ FAIRE CAME TO THE SUPREME COURT

October 1942 Robert K. Carr '29LAWYERS AND THE CONSTITUTION: HOW LAISSEZ FAIRE CAME TO THE SUPREME COURT Robert K. Carr '29 October 1942

SUPREME COURT, by Benjamin R. Twiss'34. Princeton University Press, 1942, 271 pp. $3.00.

I I ITS THIS REVIEWER NEVER had the privilege of knowing the late Ben Twiss who at the time of his tragic death at the age of a 8 was teaching political science at Hobart College. Judged by the uniform comment of those who knew him socially, his was a rare type of friendship to be highly prized. Judging by a reading of Mr. Twiss' posthumous volume it is apparent that the Dartmouth fellowship has lost a brilliant scholar who possessed a talent that was both solid and imaginative.

Lawyers and the Constitution is an exposition of the thesis "The development of law, whether written or unwritten, is primarily the work of the lawyer. It is the adoption by the judge of what is proposed at the bar." More specifically, Mr. Twiss has taken the work of the United States Supreme Court between 1890 and 1935, one of the most strongly conservative periods in the Court's history, and examined it in the light of this thesis. Analyzing in much detail the speeches, legal treatises and case briefs of some eight or ten of the most influential lawyers of the period Mr. Twiss first shows the close association that existed between the ideas held by these lawyers and the dominant conservative business philosophy of the day, and then proceeds to prove the considerable extent to which the Supreme Court drew upon these ideas in the rendering of the great constitutional decisions of the period.

Professor E. S. Corwin, the great professor of constitutional law at Princeton, prepared the volume for publication and also wrote a foreword for it. Dartmouth men will appreciate the high praise he bestows: "Ben's was a rare, an exhilarating nature, one which combined great gifts of mind and character with unusual charm of personality. As student, athlete, companion, and friend, he had won the love and admiration of hosts of his elders and of his contemporaries alike. In the presence of the world tragedy, so much of the weight of which falls upon the inexperienced shoulders of our young men, it is consoling to realize from this example that length of life is not always essential to completeness of living. Short as his life was, Ben Twiss lived successfully."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

October 1942 By John French JR. '30 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Tom Braden '40

October 1942 -

Article

ArticlePresident's Address Opens 174th College Year

October 1942 -

Article

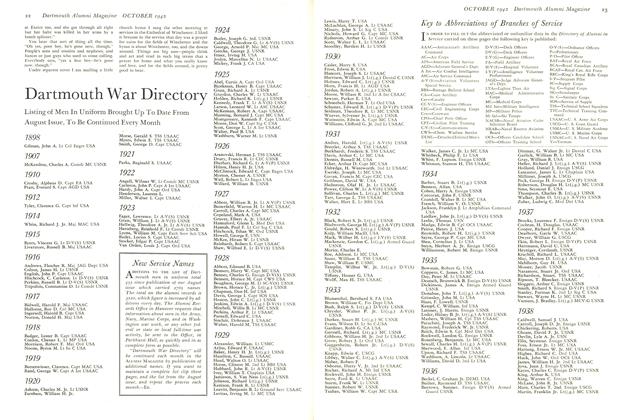

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1942 -

Article

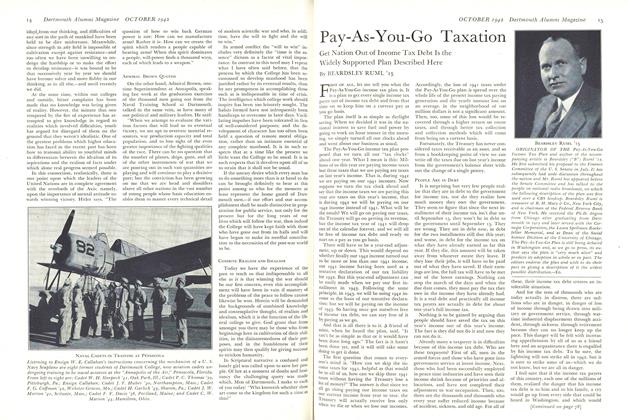

ArticlePay-As-You-Go Taxation

October 1942 By BEARDSLEY RUML '15 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

October 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

Robert K. Carr '29

Books

-

Books

BooksCONSTITUTION AND HEALTH.

June 1934 By Colin C. Stewart Jr. -

Books

BooksCONTRABAND

June 1936 By Henry M. Dargan -

Books

BooksCOPS OR CORPSES,

November 1948 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksLE HIBOU ET LA POUSSIQUETTE.

January 1962 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Books

BooksBLACKS IN THE INDUSTRIAL WORLD: ISSUES FOR THE MANAGER.

February 1975 By ROBERT MUNRO MACDONALD -

Books

Books87 MILLION JOBS.

JUNE 1963 By ROGER H. DAVIDSON