by Francis E. Merrill '26, (Editor), Ralph P.Holben, Robert E. Riegel, Earl R. Sikes andElmer E. Smead. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1946, pp. 660, xvii. $3.50.

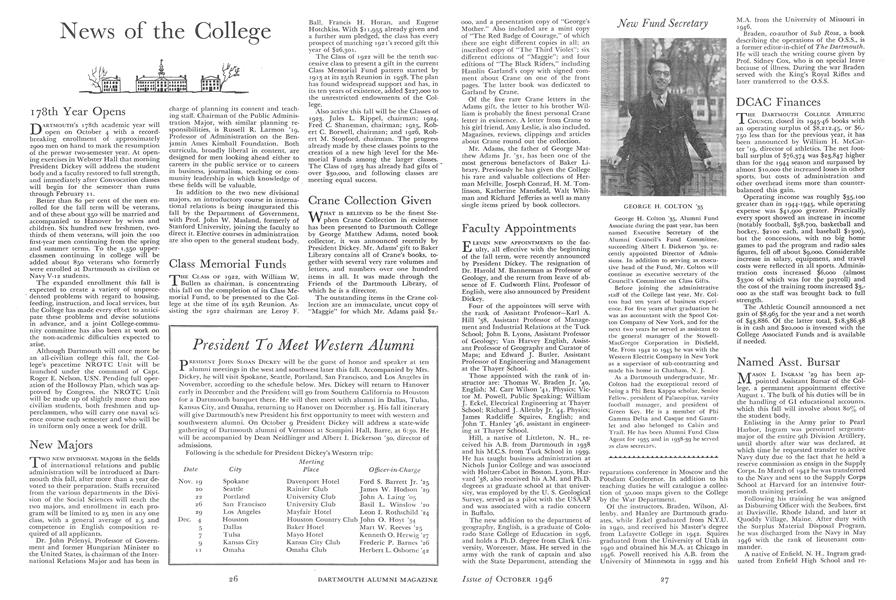

This is a one-volume edition, completely revised and rewritten, of the two-volume Introduction to the Social Sciences by the same authors, which was published in 1941. Both books were written by members of the Dartmouth faculty who taught in the sophomore Social Science course which was a part of the College curriculum between 1936 and 1945. This course, in turn, was part of the very notable program of orientation work in the social sciences which Dartmouth developed during that period. In view of the present tendency of the great liberal arts colleges to turn in the direction of such survey courses it is both ironical and regrettable that our own pioneer effort should have been a war casualty. Fortunately, this and its parent volume remain as permanent reminders of the successful courses once available to Dartmouth freshmen and sophomores.

The present volume contains thirty-seven chapters. Professor Merrill, who is the general editor of the volume, is the author of six chapters on Social Organization and the Family; Professor Riegel has eight chapters on Population, Race Problems, Business Organization, and Labor; Professor Holben has five chapters on Crime and the Criminal; Professor Smead has nine chapters on Government and Politics; and Professor Sykes nine chapters on Price, Credit and Public Finance. Thus the volume ranges widely over the subject-matter of social science and its comprehensive character is readily seen. The writing is on a uniformly high level. Without exception, each author shows a thoroughgoing technical proficiency in his own field, and yet each is also adept at making his material interesting and understandable to the introductory student. Textbook writing has of late been ridiculed by academic sophisticates who for some strange reason seem to feel that to systematize knowledge in a well-organized, readable book is to commit a crime. This volume illustrates the shallowness of that position. Textbook it is, but it is an effort in which Dartmouth may well take great pride. The social science faculty of no other American educational institution has produced a sounder or abler book. It is certain to be widely read and used, and in that process to bring great credit to the name of Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

October 1946 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS, SUMNER B. EMERSON -

Article

ArticleOPERATION CROSSROADS

October 1946 By WILLIAM J. MITCHEL JR. '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Coming "Boom and Bust"

October 1946 By BRUCE W. KNIGHT -

Article

ArticleCan We Achieve Economic Stability?

October 1946 By JAMES F. CUSICK, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1946 By ERNEST 11. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

Robert K. Carr '29

-

Books

BooksLAWYERS AND THE CONSTITUTION: HOW LAISSEZ FAIRE CAME TO THE SUPREME COURT

October 1942 By Robert K. Carr '29 -

Books

BooksTHE BATTLE AGAINST ISOLATION.

January 1945 By Robert K. Carr '29 -

Books

BooksON THE TEACHING OF LAW IN THE LIBERAL ARTS CURRICULUM.

June 1957 By ROBERT K. CARR '29 -

Books

BooksWhat Went Awry in Miami

May 1975 By ROBERT K. CARR '29

Books

-

Books

BooksHardy Rye

MAY 1927 -

Books

Books"Week-day Religious Education in America" is the title of a paper read before the Contemporary Club in Davenport, Iowa,

JUNE, 1928 -

Books

BooksTHE BIRDS OF MASSACHUSETTS AND OTHER NEW ENGLAND STATES

MAY 1930 By B. B. Leavitt -

Books

BooksFAREWELL TO FOGGY BOTTOM.

DECEMBER 1964 By HON. ROBERT CHARLES HILL '42 -

Books

BooksSOMMETS LITTBRAIRES FRANÇAIS.

June 1957 By HUCH M. DAVIDSON -

Books

BooksTHE DREAMER OF DEVON

November 1932 By John Hurd Jr.