It is hard at this time of year, in this outpost of the civilized world, not to think about Nature and life and the state of things in general. Partly it's due to this special place called Hanover, and partly it's a state of mind brought about by the inexorable progression from summer to fall. As usual, the Bard of Avon had something relevant to say about all of this-and as usual, an inimitable way of saying it. His 73rd sonnet begins: That time of year thou may'st in me behold When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

It has always been one of my favorite passages, focusing, as it does, on the evanescence of life, the swift passage of time; and Shakespeare does it with a nostalgic reverence for the past and a sense of what Henry James called "the felt life." What is perhaps most striking here apart from the sheer beauty of the language is the ex- traordinary brilliance of the images, particularly the way they describe a complex web of interconnected ideas. The movement in the second line from perceptible objects ("yellow leaves") to barrenness ("none") back to the reality ("few") hints at the narrator's own mental journey from youth, when objects seem to have little symbolic value, to a terrifying awareness of death, and back again to a more tenable vision of reality. The subsequent shift to the boughs brushing against the "bare ruin'd choirs" a reference to the many deserted English churches built in an earlier, less secular age and the embellishment "where late the sweet birds sang," refer obliquely to the untutored joys-of Nature as well as to the more structured discipline of choirboys and the music they once created. There are of course other layers of meaning here, but the point is that Shakespeare uses the natural world as a point of departure for examining the narrator's inner thoughts.

Here, where the demarcation of the seasons is severe, where late in summertime you will get a blast of cool air as if to warn you that winter weather is just around the corner, the passing of time finally nips you at some point in life. It is something like driving along one of those glorious stretches of New England pavement where a spectacular vista lays itself out before you and as far as you can see there is nothing but a symphony of green foliage played out against a patchwork of neatly hewn fields. And then you notice one rebel tree which has jumped the gun on nature and turned red too early in the season. Thoreau delighted in this sort of anomaly a tree, dancing so to speak, to the music of a different drummer, defying the prescribed course of things.

Nature's moods and contrariness have intrigued American writers, artists and common folk from the beginning. And some of our best writers Dickinson, Emerson, Thoreau, and Frost among them tried to "read" human relationships against the backdrop of Nature. It is almost as if the attractions of this rugged stretch of the universe were embedded if not in their muscles then surely in their minds and souls.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

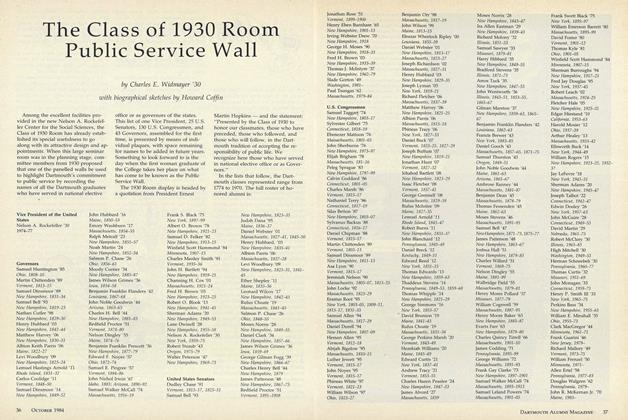

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

October 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Cover Story

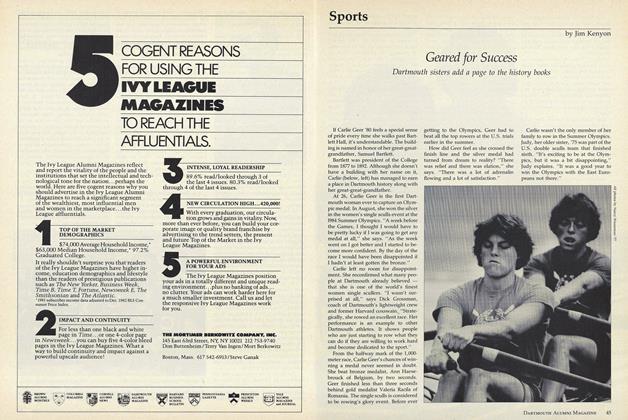

Cover StoryGeared for Success

October 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

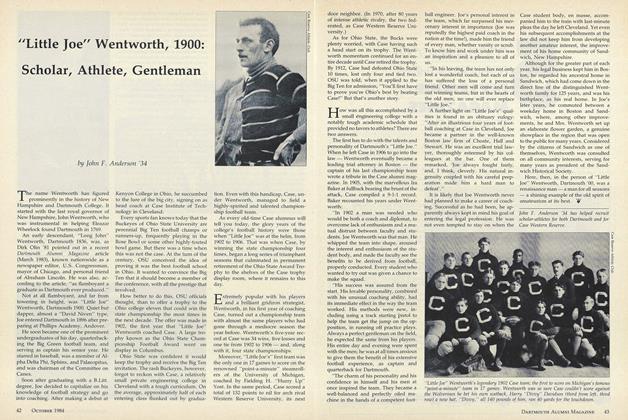

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

October 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

Feature"The Computer Revolution" Revisited

October 1984 By George O'Connell -

Article

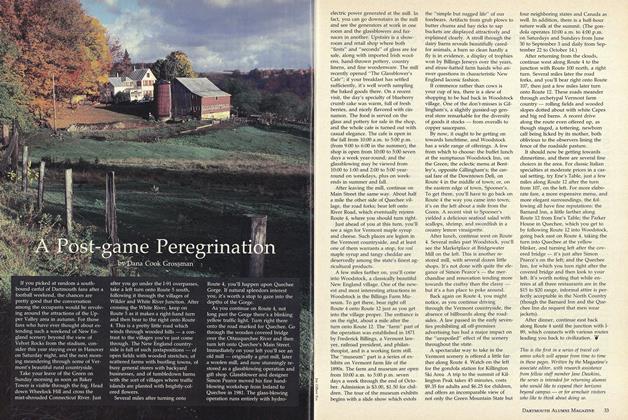

ArticleA Post-game Peregrination

October 1984 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Article

ArticleGetting Better with Age

October 1984 By Gayle Gilman '85

Douglas Greenwood

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorSettling in in Hanover

JUNE 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPassages

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorOn Being No. 1

MARCH 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorBetween the Lines

DECEMBER 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

MARCH • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Article

ArticleFootnotes on an Annual Report

MAY 1985 By Douglas Greenwood

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA SecondLetter, Dated May 9

June 1924 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

MARCH, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

January 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorBetween the Lines

DECEMBER 1984 By Douglas Greenwood