A Glimpse at the Magic of Good Writing By a Doctor of Particular Distinction

WHEN, IN JUNE, 1935, I returned from Dartmouth with the honorary degree, and plumage appertaining thereto, received with still unsubsided amazement at the hands of President Hopkins and counted among my most prized possessions, to the little village in the Helderbergs where I lived at that time, one of my farmer neighbors, hearing that I might now be addressed as "Doctor," came to me with the hope that I could tell him what was the matter with one of his cows. Yes, he was quite serious—if a doctor, why not?

"No, I'm not that kind of a doctor," I said. "I'm not a Doctor of Medicine—not even a veterinarian. The degree Dartmouth gave me is that of Doctor of Humane Letters."

His eyes opened wide and his jaw fell as he demanded: "What the hell is a 'humane letter'?"

I could not even tell him that!

Yet his question went to the roots of a subject that has been puzzling me all my life. Ever since I was a little boy I have been writing; the impulse to do it seems irresistible and incurable; no doubt I shall continue an addict until the end, as Whitman says, "garrulous to the very last." And to that "very last" I shall be wondering, as I wonder now, what it is that I am doing, with these arbitrary marks on paper. Right now, stringing them along in groups, here in Florida, in hope of making something happen in other fellows' minds a thousand miles and more from here. For twenty-five years I have been trying to put together an essay, under the caption, "The Magic of Writing"; I find the task increasingly baffling. "For nothing short of magic it is; instead of Doctor of Humane Letters I might better have been granted the "M.A."- Magician's Apprentice—for lam still trying to figure out the real nature of my trade.... like the psychologist having some slight aptitude for processes and techniques but completely in the dark as to the essential nature of the susbtance around whose edges he bushwhacks gropingly.

I hear a lot of precious twaddle from writers and professors of English about "self-expression," "style," and whatnot else of the abracadabra of our cult; but it leaves me cold—when it doesn't make me laugh. "Self-expression"? To whom? "Style"? What does that mean? The more "style" you have the more it interferes with the thing you are trying to do. The more peculiar and "individual" it is, the more you are obstructing with your own posturing self your ostensible purpose of getting your Idea over to the Other Fellow—which is the only excuse for writing; or talking, or painting, or sculpturing, for that matter.

But even that statement is fallacious; for you are not trying to get your Idea over. You can't do it, unless the Other Fellow already has it, latent and unrealized perhaps, but there in all its elements. In a very real sense, you cannot tell anybody anything that he doesn't already know. In other words, you can work only with and upon the material of his experience. Your writing, your procession and arrangement of words—and above all they must be words meaningful to him—must incite him to scrabble about in his memory for scraps from his experience, and newly arrange them into a pattern as nearly as possible like the one in your mind. If his experience is in no respect like yours, you have no material to work upon and can tell him nothing. That is why the farmer said upon seeing the dromedary, "They ain't no such animal!" Not a fraction of the beast existed in his mental experience—he couldn't even imagine him, though there before his eyes.

WRITING FOR THE READER

So, in human—or, let us call it humane- communication, it is more important for the writer to know and write in the vocab- ulary and the terms of the reader's experi- ence than in those of his own. As Henry Clay Trumbull said of teaching, unless something is learned, nothing is taught. The success of the writer, and his ability as such, is measurable absolutely so far as con- cerns his communicating anything, by the degree in which the reader gets him. A veteran missionary told me of a group of Swedish Christians convinced that the Sec- ond Coming of Christ would be deferred until every man, woman and child in the world was informed of its approach. A del- egation of them came through the Chinese village where this missionary lived, up and down every street and alley, punctil- iously declaiming, "Christ is coming! Christ is coming!". . Informing their politely amazed auditors of—nothing whatever; they heard only meaningless funny noises.

Lots of writing is like that; the authors, literary snobs, proudly displaying their vocabularies, juggling their ostentatiously queer idiosyncrasies of construction alias "style," do their stuff complacently, imagining that they are imparting something momentous momentously; but their projectiles are duds. As Frank Tinney used to say of his piccolo-playing, "I blow it so sweetly; and it comes out so rotten!" The proof of any pudding is not in the self-conscious technique of the cook, but in the enjoyment and benefit of the eating.

Upon a certain day in November, 1863, one Edward Everett spoke for more than three hours; one Abraham Lincoln spoke for two-and-a-half minutes. You would have difficulty in finding the text of Everett's speech; every school child knows by heart what Lincoln said; his Gettysburg address is immortal. Why? I do not know. Simplicity, brevity—yes; but it is something more than that. Tell me what it is about Keats, about the Twenty-third Psalm, about—any other of the writings with marks on paper that grip the hearts of men —that makes all the difference. It's magic, I tell you.

I do not know what it is, though all my life I have been searching for it, as one with a microscope might search for the secret of the beauty of a flower, with a telescope for the poignant charm of a landscape, with a scalpel dissecting for the secret of a great man's greatness.

One thing I have found out; that is that the art of it abides not in the tools, the vocabulary, the etymology and syntax, important though they be; but in the writer's understanding of and sympathy with the reader, with him to whom he speaks. By sheer magic, effortless as the movement of a reciprocating engine—better still as the song of a meadowlark—he must enter into and command the spirit of his auditor, compelling him to attune his resources of mind and memory and imagination in response. St. Paul said it: "Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not sympathy, understanding, love . . . sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal."

JOHN PALMER GAVIT received the honor-ary degree of L.H.D. (Doctor of HumaneLetters) at the hands of President Hopkinsin 1935- His journalistic career has been along and notable one. He was managingeditor of the N. Y. Evening Post for severalyears, head of the Washington bureau forthe Associated Press during another pe-riod, and more recently an author on edu-cational and international affairs, andassociate editor of The Survey. He has al-ways been active in social welfare work.His book College, published in 1924, isread today as a keen analysis of Americanhigher education. He describes therein hisfirst visit to Hanover.In conferring the honorary degree onDr. Gavit, President Hopkins said in hiscitation, in part: "To all hypocrisy andsham you are a bitter foe; of all arroganceand self-righteousness you are a revealingcritic; but to the downtrodden, the op-pressed, and the defenseless you are afriend beyond compare The diversityof your interests, the variety of your ex-perience, and the versatility of your talentsdefy classification."

DOCTOR OF HUMANE LETTERS, DARTMOUTH, 1935

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

February 1939 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleA Freshman Writes Home

February 1939 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

February 1939 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

February 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

February 1939 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

February 1939

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA LETTER FROM ED STOCKER

January, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters

June 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

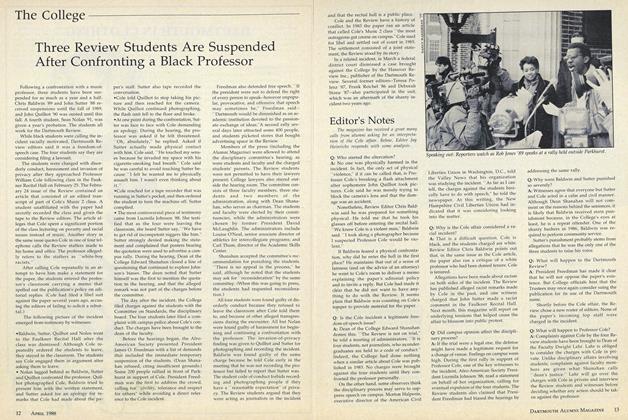

Lettter from the Editorthe magazine has received a great many calls from alumni asking for an interpretation of the Cole affair.

APRIL 1988 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorVisions and Revisions

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Douglas Greenwood