Sidney C. Hazelton '09 Has Taught Red Cross Course To More Than 1,000 Enthusiastic Volunteers

IT MIGHT BE the fireman's drag when the teacher is willing to do the dirty work himself, getting down on his knees, getting his trousers dusty, using a lot of strength, and making himself look a trifle silly, or it might be the nicety of the demonstration of the traction splint when he remembers every detail as a little work of art. There is something about the way Sidney C. Hazelton '09 teaches first aid which has fascinated his classes from 1936 through 1942.

He has the ability to rivet attention on himself from the outset. One way is to tell the story of a Hanover man whose automobile careened off the road over in Vermont and catapulted him through the roof into a field. "I'm hurt something dreadful," he said to the would-be rescuers, who, untrained in first aid, had consternation on their faces and ignorant willingness in their hands. "O. K.., Don't worry," they said. "We'll get you to the hospital all right. And pronto." And so they yanked him into a sitting position, dragged him over a stone wall, propped him up in the car seat, bumped him at teeth-chattering speed over rough roads, stumble-walked him into the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, and poured him into a chair.

"It was a classic case of what not to do in first aid," says Sid Hazelton, as the class, horrified, listens to the words they never forget and to the ending they always remember. "Try to recall every action and how you should never imitate it. You see, the man had serious internal injuries and a broken spine. He was 'hurt something dreadful.' Before the doctors even looked at him, he died in the waiting room."

Human beings love to tell about accidents. Sid Hazelton's first-aid classes want to talk about the man over Etna way who drowned and recovered by being stood on his head, the baby at Lyme Centre who burned himself somewhat by falling into deep fat, the girl in West Lebanon who was almost run over by a train and threw a fit, and the white-bearded grandfather who drank Paris green and turned black. Sid is polite, but he dominates his class in a firm and gentlemanly way, lets the stories come out if they are terse and pointed, and chokes off the irrelevant details.

And he takes just about the right attitude towards blood. It is so easy to be sensational about gore. Consider the poor man with his throat cut. You can approach the problem of what to do in terms of a geyser of blood spurting up and over you, the slipperiness in trying to check it, the noise in the gullet of the dying unfortunate, and your clothes covered with clotted drench. That is one way of doing it. After all, we are in the war, and the world is no longer one for the squeamish and the finicky. First aid deals with violence and terror and tragedy. But Sid is nice and kindly and wholesome in his realism. He describes the difficulty a first-aider has to face in handling a severed jugular vein in terms of a pressure point that can be controlled about as easily as a piece of cooked macaroni that you just can't get your fingers on and hold fast to.

The ability to use the vivid phrase which shocks but does not revolt is part of Sid Hazelton's technique. The American Red Cross First Aid Textbook and the one for Advanced First Aid emphasizes facts. As a former member of the Department of Romance Languages at Dartmouth, Sid Hazelton knows a thing or two about the inability of persons to absorb facts unless they are made dramatic. So in his first-aid teaching he has the neat trick of coining phrases and making associations with letters that help his pupils to remember.

This is how his system works. Supposing you want to remember what are the symptoms of a man suffering with severe internal bleeding. "He's RAPT," says Sid. "Restless, Apprehensive, Paler and Paler, and Thirsty for air and water." (The first letters spell the word.)

Unforgettable is the sentence to give learners the right answer about symptoms of infected wounds. Under the teacher's guidance they chant, "Poor Sid ripped his pants, rear seat torn." Translated for use on the examination, the sentence reads, "Pain, Swelling, Red, Heat, Pus, Red streaks, Swollen glands, Tenderness."

Think of how SAD it is to have a man "unconscious," says Sid. And so one remembers why the condition may have arisen, from skull fracture, apoplexy, or drunkenness.

Raise the question of a sufferer from frost bite and a member of Sid's class will cry, "Aha, one of the CCC boys." This means that the proper treatment is Contact (the frozen hand held against you), Covered, Cool (in air or water about 40 or 55 degrees).

These devices are the tricks of the trade. Equally valid is the picturesque comparison. Slightly forgetful, you might not remember why you should not rub frost bites too hard. Sid tells you that tissue is like cream on top of a quart milk bottle when a cold night comes and the cream freezes and pops up. Something analogous happens to frozen tissue. It's more than cream that you will be skimming off'if you rub too hard.

Sid Hazelton did not plan to become the first-aid teacher he has. He first got interested in 1936 at South Hanson, Massachusetts, where he took a course himself in connection with the aquatic school there. Somehow he got asked to instruct the Dartmouth Outing Club Heelers who are always running into the need for first-aid, the Hanover Fire Department, the Medical Students, and, of course, the Red Cross members. When the war came and the Hanover Office of Civilian Defense set up an elaborate pattern of interlocking committees to serve in planning against possible air raids, Sid found himself very busy. In six years more than 1,000 men and women of all sorts and conditions, professors, storekeepers, mechanics, farmers, factory workers, housewives, from Hanover, Woodstock, Croyden, Lebanon, Norwich, and Wilder have taken courses under him.

He could not handle so much work alone, and qualified instructors have assisted him: Ross McKenney, Albert P. Stewart, Wilson B. Dunham, Mrs. Bertha Waite, Mrs. Winifred Hadlock of Lewiston, Mr. and Mrs. G. William Cossingham of Norwich, Mrs. Bessie Rogers, Mrs. Constance Trachier, Hannah Croasdale (the technician in Silsby), Elliot B. Noyes, John Rand, William Danforth, Everett Johnson, and Alice Cox.

Asked how many of the thousand have failed under him, Sid's answer is, "The number who have failed can be counted on the fingers of one hand. College professors are not quicker to learn than others; they are no cleverer with their hands and have no better judgment. Women are smarter than men especially with their fingers and their intuition in the care and handling of the wounded. The hardest task facing me is to teach how to handle fractures and the proper application of splints, when and how to apply them. It is not easy to calm people down in a crisis and to teach them proper ways of transporting one who has been in an accident. Skilful artificial respiration is difficult, and so are pressure points."

One of Sid's slogans which he coined himself and repeats to this day with the same pleasure as when he first thought of it is: "Better to do nothing intelligently than to do something stupidly." Sometimes conserving breath, he says, "No bluffing."

Classes last two hours. During the first, Sid talks from the textbook to which he sticks very closely though once in a while he will let an aside creep in, how some hospitals don't use the Red Cross method of making persons suffering from severe nose bleed lie down, which may lead to nausea, but prefer the basin or the salt pork method. He may explain the refusal of the Red Cross to allow water on wounds arises from the fear of contaminated wells and rivers in rural communities. During the second hour, people watch him doing his demonstrations and then try a cravat bandage of the ear, a traction hitch of the hand, or board splints for a fracture of the forearm. Occasionally difficulties arise that need Sid's advice such as the location of pressure points on a very fat man.

The classes like the dramatic interludes Sid enjoys introducing such as pictures of snakes and a photograph of a man's hand which has been bitten by a poisonous variety and the way a knife should cut the flesh to insure proper bleeding which will carry away the poison. What with the war, the blackouts, and the numerous bombers that do belly rolls while roaring a dozen feet above the campus elms, Sid finds that people get a mild shudder when they sniff poison gases to distinguish which smell is deadliest: garlic, new-mown hay, geranium, coal gas, mustard, or appleblossom.

It is no wonder that persons stay not only for the entire two hours but also even hang about for a quarter of an hour afterwards to ask questions or to air their knowledge. They like Sid, they say, for he has tact and kindliness and enthusiasm, and, never hurting feelings, he spurs people on to answer better than they really know. On his part, even after six years he finds classes invigorating. "Time after time when I have been so tired I felt I could hardly go out, the class would pep me up and make me feel fine," he says. It may be that he is motivated by the love of teaching and the desire of being useful, for the job carries no salary and the hours are wearing and what with tires and gas these days, Sid may be losing on the expense money returned to him by the Red Cross in Washington.

His students praise him for a variety of skills, but they agree that he shows himself to be particularly adept in doing artificial respiration, more difficult to learn than most people realize, for the tendency is to squeeze too hard, to fail to get the little finger tucked in just right below the last rib, and to exert pressure so strongly in wrong places that the insides get compressed with the possibility of injury. And he is adaptable. Alice Cox, for example, devised a stretcher with poles, a blanket, and a shutter, whereas the book omitted the shutter. Sid saw the improvement and told about it enthusiastically at the next class. Once he had to transport an injured person at a lake when there was nothing to move him with except a rope. He managed to knot it together as a sort of hammockstretcher capable of being used when persons held the rope ends along the side.

The courses in first aid led to Sid's career in the Fire Department where he is Assistant Chief under Chief Carlton Nott, who says of Sid that when it comes to joking, he is good. "He's a corker. Fits right in with the boys," is Carl Nott's way of putting it. Another member of the Department describes Sid as follows: "All of us like him and want his respect, for he is a real man with a deep sureness of himself, his hands, and his technique." In exciting moments his voice is steady and reassuring and deep; he does not raise it and blow the men off balance.

Asked what the most spectacular event in Sid Hazelton's career as Assistant Fire Chief, Carl Nott smiled his slow and deliberate smile and spoke in his slow and deliberate way, "Well, I should say that it was when Sid climbed a fifty-foot ladder."

If you know the man, you see the picture. Six feet two and a half inches tall, he weighs 220 pounds and looks not fat but massive. The sight of the giant who has been down on his knees to illustrate the fireman's hitch and to crawl along with the unconscious victim now hauls up his own powerful body on puny rungs 50 feet up into the air and provides a spectacle more arousing than any ordinary fire.

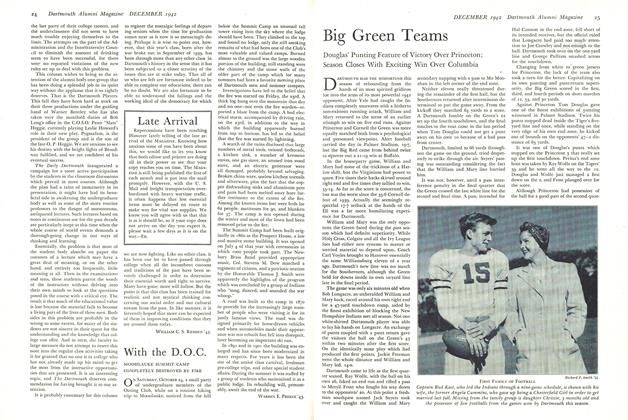

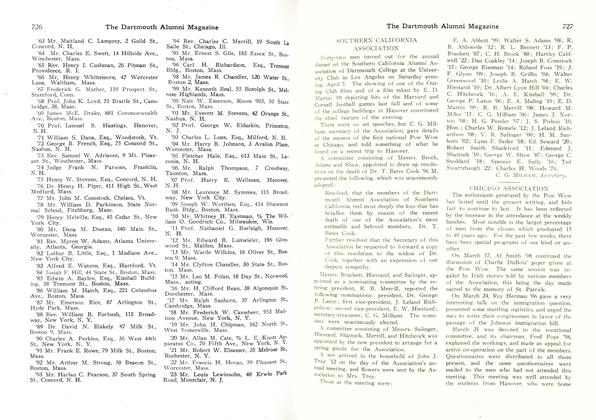

SID HAZELTON GIVES HIS CLASSES A REAL WORKOUT Everybody hits the floor for traction splint practice and they do all right too. About1,000 volunteers have taken Sid's Red Cross courses in Hanover and neighboring towns.Note that coeds are liberally enrolled in his instruction groups.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

December 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Five Maries

December 1942 By WILLIAM CARROLL HILL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1942 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

December 1942 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1942 By Elmer Stevens JR. '43 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

December 1942 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS

JOHN HURD '21

-

Books

BooksALEXANDER POPE'S EPISTLES TO SEVERAL PERSONS (MORAL ESSAYS).

MAY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksSHEAF OF OATSTRAW.

JUNE 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksDOUBLE TAKE.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFLAUBERT IN EGYPT: A SENSIBILITY ON TOUR. A NARRATIVE DRAWN FROM GUSTAVE FLAUBERT'S TRAVEL NOTES & LETTERS

December 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBIG BUSINESS – YOUR LIFE WITHIN IT.

October 1974 By JOHN HURD '21

Article

-

Article

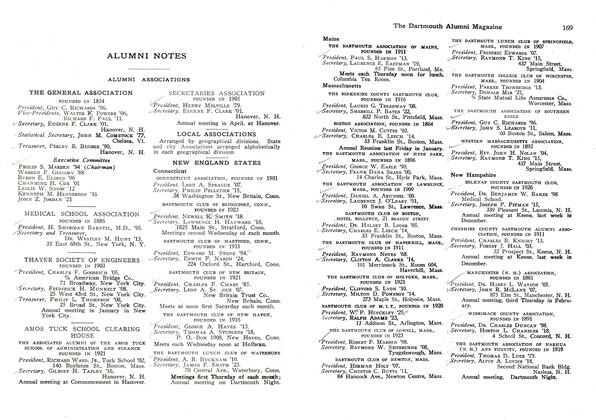

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

December, 1925 -

Article

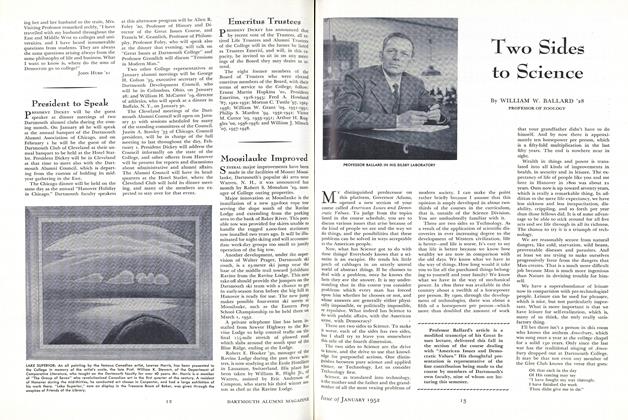

ArticlePresident to Speak

January 1952 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE AND PHYSICAL FITNESS

February 1925 By Dr. William R. P. Emerson '92 -

Article

ArticleNathaniel Fuller '67: Back to Center Stage

MAY • 1987 By K.E -

Article

ArticleThe Review's Competition

MAY 1989 By Sarah B. Meyers -

Article

ArticleCHICAGO ASSOCIATION

June 1924 By Warren D. Bruner