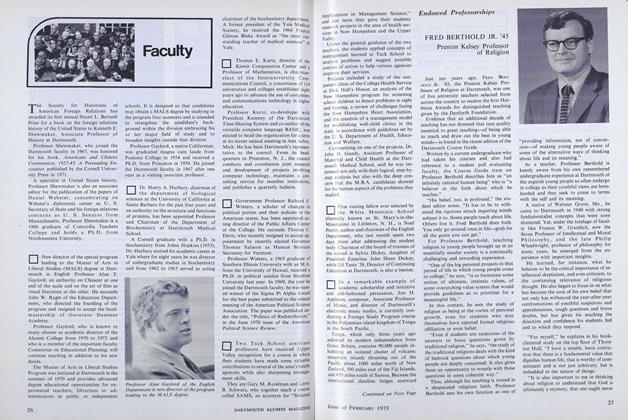

Professor of Physiology

In the world of medical science, the name of Dr. Heinz Valtin is inseparably jinked to that of the "Brattleboro Rat" - but as a compliment and with the respect that special achievement merits.

From Prague to Palo Alto, Valtin is recognized as a leading authority on the physiology of the kidney, especially the genetic determinants of the complex mechanisms by which that vital organ regulates the conservation or release of body water.

He made one of his big breakthroughs in the study of renal functions when early in the sixties he managed to breed a special strain of hooded rats with a hereditary disease called diabetes insipidus. The term, which comes from the Greek, is literally translated as "the passing through" (diabetes) of "tasteless fluid" (insipidus) and simply describes any mammal's in- ability to hold or conserve life-sustaining water in the body.

Development of the strain was important because it provided medical scientists a significant new tool for studying kidney functions. The study of this strain of rats with a critical kidney malfunction can produce - indeed has produced - measurable reference points for advancing knowledge about normal renal functions. As a result, Brattleboro rats - now many generations old - are in medical research laboratories all over the world, wherever work is going forward on the kidney. That organ has had a special importance ever since life left the sea to develop on land because it preserves in the body the vital balance of water and salt.

In naming the Brattleboro Rat, Valtin nought to honor Brattleboro, Vt., where the "great, great, great grandmothers" of the strain were born. There Dr. Henry A. Schroeder of the Dartmouth Medical School Department of Physiology maintains an isolated mountainside laboratory. Then, as now, he was raising a colony of normal rats in connection with studies of the role of trace metals in causing heart disease.

An alert animal keeper noticed in 1960 that the drinking bottles in one of the cages, where a rat had just had a large litter, always seemed to be empty. It was then noted that six of the young rats were drinking excessive amounts of water and immediately passing it through. That clue led to the discovery that those six rats had hereditary hypothalamic diabetes insipidus - the first time, as far is known, that the rare disease had been found in a common laboratory animal. Until then, it had been described only in man.

Schroeder, recognizing that the diseased animals offered a unique opportunity for studying that malady, gave the four surviving females to Valtin. For long-range research purposes, it was necessary to breed more diabetic rats, and for several frustrating months, Valtin and a collaborator, Dr. Hilda Sokol, fought against failure. The rats initially tended to produce litters which were either sterile or suffered 100 per cent mortality. Finally, after nine months of trying, Valtin and his colleagues made a surprising discovery: The rats needed a secluded, quiet environment. Then the right combination was found and the strain started.

Although his research has been mostly with rats - now joined in his laboratory by several strains of mice from Edinburgh, Scotland - Valtin is currently studying two area families afflicted with the hereditary problem.

For such persons, his work has already provided some relief. In collaboration with Dr. William O. Berndt, associate professor of pharmacology; Dr. William M. Kettyle, a former medical student and research fellow, and Dr. Michael J. Miller, a graduate and medical student from Kingsford, Mich., Valtin has, for instance, confirmed the value of a drug called chlorpropamide in the treatment of hypothalamic diabetes insipidus and established clues as to how the drug worked, after it almost accidentally was found to be helpful to sufferers of the disease.

The significance of his early research was recognized in 1964 with a Research Career Development Award, spanning 10 years, from the National Institutes of Health.

In more recent years, Valtin has reinforced his studies with the Brattleboro rats and Edinburgh mice by developing computer models to simulate certain kidney functions and test theories about actual kidney behavior as one or another variable is altered. Valtin was assisted in this work at the Kiewit Computation Center by Dr. John Stewart, a postdoctoral fellow from the British Medical Research Council.

Alongside his research concerns, Valtin regularly teaches in the M.D. program and works closely with the post- and predoctoral students. Conscious of the changing nature of M.D. curricula, yet concerned that basic medicine continue to be soundly taught, he has written a textbook for first-year medical students entitled "Renal Function: Mechanisms Preserving Fluid and Solute Balance in Health." And now a sequel for second-year M.D. students is in the typewriter.

He is currently director of a training program in renal function and disease sponsored by the National Institute of Arthritis, Metabolic and Digestive Diseases. He also serves as a clinical consultant in kidney diseases for the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital and as medical adviser to the ABC (A Better Chance) Program in Hanover.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, 47 years ago, Valtin and his two brothers were brought to this country in 1938 by their mother, who was allowed to take only $40 with her as capital to start a new life in America for her small family.

After studies at Hamilton and Swarthmore, Valtin received his M.D. degree from Cornell Medical School in 1953. He was an intern and resident at the Strong Memorial Hospital of the University of Rochester Medical School.

But it was a year (1955-56) at St. Andrews University, Scotland, that was critical for him. There, he met a Scottish physician, Dr. Kenneth Lowe, who was a specialist in kidney diseases. Valtin worked closely with Lowe, who encouraged Valtin to try his hand at academic medicine by enlisting his help in preparing three different research papers. When the year was over, Valtin had given up his early plans to go into practice in some remote area like the Ozarks and had decided to engage in medical research and teaching.

With that decision made, he began to think of men with whom he could associate to get further training in research. For Valtin, the choice was clear. It was Dr. Marsh Tenney '44, whom he had known and admired on the faculty at Rochester. And when Tenney moved to the Dartmouth Medical School to begin a long process of its "refounding," Valtin followed in 1957 in what he regards as one of the "best decisions of my life."

The Vail Professorship was established at the Dartmouth Medical School last year through a $500,000 endowment gift from Mr. and Mrs. Foster G. McGaw of Evanston, Ill., in memory of Mrs. McGaw's grandson, Andrew C. Vail, who died of kidney disease at the age of eight. The boy's father, James D. Vail III of Lake Forest, Ill., is a member of the Dartmouth Class of 1950, and his grandfather, the late James D. Vail Jr., was graduated from Dartmouth in 1920.

The gift to the medical school is the most recent of many benefactions in support of health care and education by Mr. McGaw, founder and honorary chair of the board of American Hospital Supply Corp., and his wife, the former Mary Wettling Vail. They were major contributors to Dartmouth's new $7.5 million James D. Vail Medical Building now nearing completion, which will double the research and teaching facilities of Medical School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

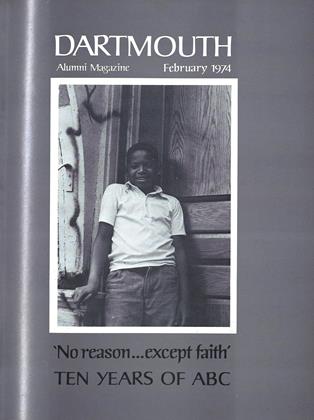

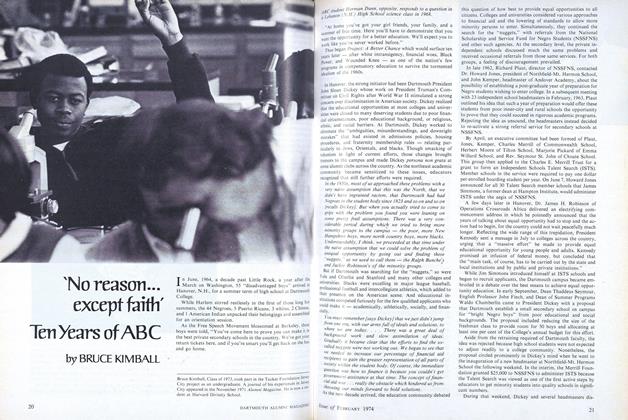

Feature‘No reason... except faith' Ten Years of ABC

February 1974 By BRUCE KIMBALL -

Feature

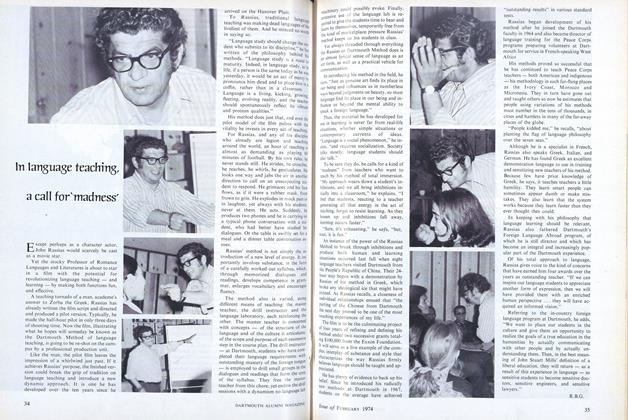

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

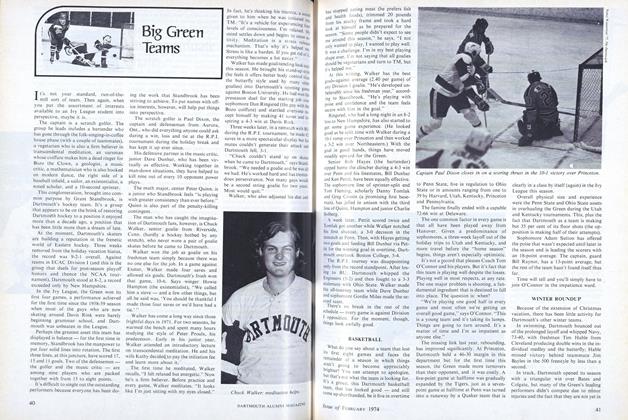

ArticleBig Green Teams

February 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

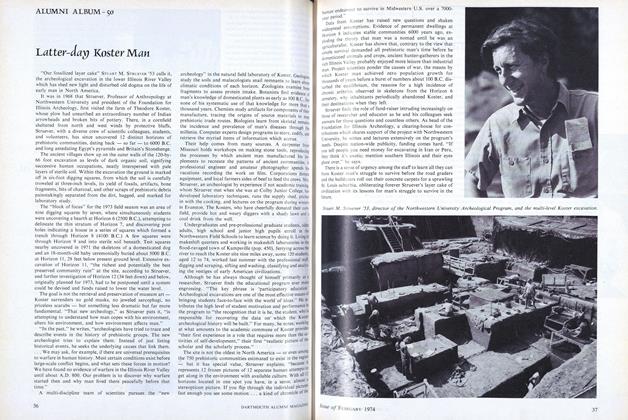

ArticleLatter-day Koster Man

February 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1974 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Article

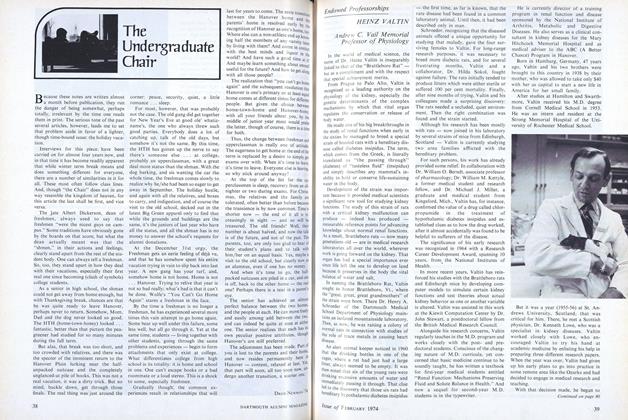

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1974 By DREW NEWMAN ’74

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleEndowed Professorships

FEBRUARY 1973 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleGORDON J.F. MACDONALD

October 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleERNST SNAPPER

January 1974 By R.B.G. -

Feature

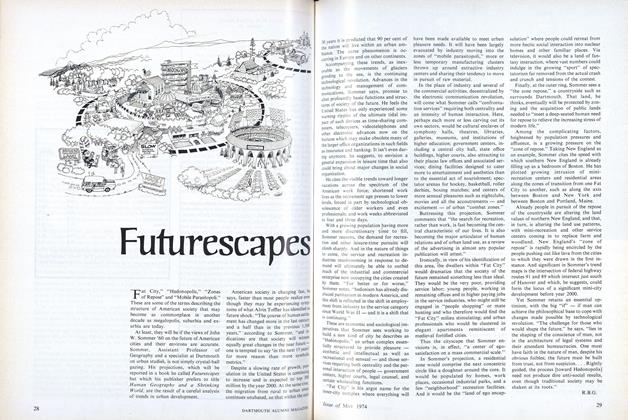

FeatureFuturescapes

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleS. MARSH TENNEY

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

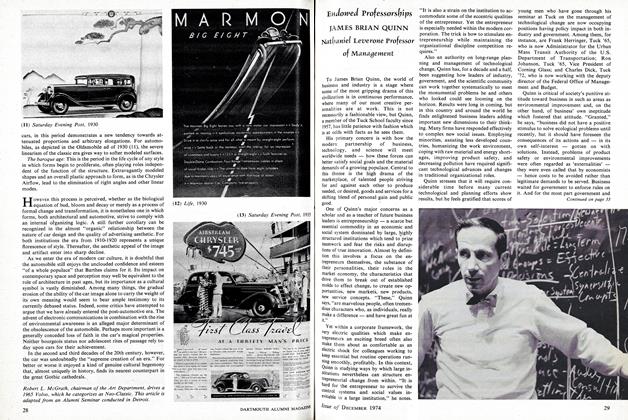

ArticleJAMES BRIAN QUINN

December 1974 By R.B.G.