Boswell called Fanny Hill "licentious and inflaming." Others extolled it as "a paradise of erotic fantasy." Or condemned it as a hell "too infamous to be particularized." "Best forgotten," the author was "an unfortunate and worthless man of letters." But since 1748 John Cleland and Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. its original title, have proved popular throughout the Western World. Pretending a cold, an aristocrat would lie in bed to read it. Shipping out to India, Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington, secreted it in his luggage. Benjamin Franklin and Governor Samuel Tilden of New York are reputed to have owned it. Clasping it, young women suddenly matured, and older women enjoyed rejuvenation.

Epstein has consulted the best American and British scholars and ransacked libraries, public and private. In a book of only 284 pages, his appendices, notes, lists of works cited, and index run to all of 101. The times emerge vividly; the man, less so, "a haphazard series of flickering images." Epstein "confesses" that he does not know what John Cleland looked like and whether he married.

The Cleland background is clearer. "His father dined with the Duchess of Marlborough, battled the 'dunces' with Pope, carried secret messages for the Earl of Mar, played host to Steele...; his mother enjoyed Horace Walpole's conversation, entered Chesterfield's correspondence, and willed Lady Hervey's picture." The son, creator of Fanny Hill. was educated in prestigious Westminster; aged 17, sailed to Bombay as a common foot soldier; and there in 12 years rose to power in the East India Company. Back in London, he was thrown into jail for 376 days on charges of trespass and non-payment of debt. Decade after decade he wrote novels, plays, newspaper articles; cultivate Garrick, Foote, and Smollett; and played around in medicine, deism, and antiquarianism. With echoes from Eliot, Epstein suggests that, old and dreamy, Cleland had "known them all already, known them all"; though now, after these many years, they were probably "voices with a dying fall."

The voice of Fanny has a living fall. Epstein relates "the situational hazards of a young penniless girl adrift in the turbulence of London" to those of Defoe's Moll Flanders and Hogarth's harlot. There are allusions to Fanny's bawd, Mrs. Cole; "Mother Needham, a pious procuress"; "Mother" Douglas, London's most notorious woman of pleasure; and Colonel Francis Charteris whose "method of seduction was to post agents in inn yards to spot newly arrived girls from the country."

Though to some Fanny Hill may be licentious and inflaming, too infamous to be particularized, Epstein makes clear Cleland's sensitivity to the style of the great and the near-great. Indeed, country-girl and penniless, Fanny condemns them as "superficial and unnatural, unable to appreciate 'the art of living.' " The question of why Fanny of her own free will joyfully offers her youthful body to "veteran voluptuaries" may inveigle some discriminating readers to turn against "a sallow, washy painted dutchess" and towards "a ruddy, healthy, firm-fleshed countrymaid."

But, finally, Fanny's voice is muted in a dying fall until she lives again in sackcloth and ashes. Now chaste, she is induced, so she says, to "paint Vice in all its gayest colours" only "to make the worthier, the solemner sacrifice of it, to Virtue."

IMAGES OF A LIFE. By WilliamH. Epstein '66. Columbia, 1974.Illustrated. 484 pp. $9.95.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

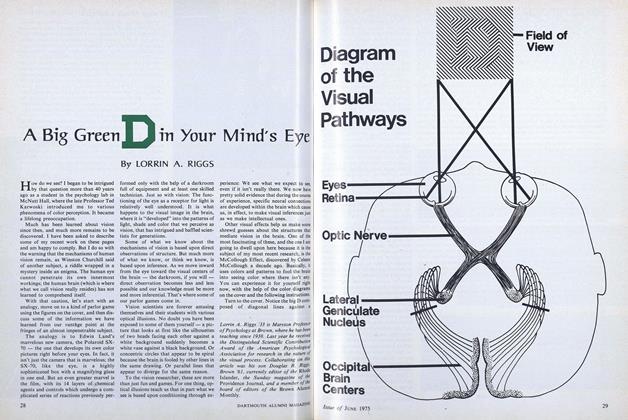

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975

JOHN HURD '21

-

Feature

FeatureSoldiers As Policy Makers

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE MOST AMAZING BUT TRUE.

JUNE 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

OCTOBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLAUGHTER AND TEARS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksQUICK GUIDE TO SPIRITS.

OCTOBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

JANUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE CONSTITUTION AND THE MEN WHO MADE IT

January 1937 -

Books

BooksTHE KING'S STILTS

January 1940 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksSUPERIOR: PORTRAIT OF A LIVING LAKE.

FEBRUARY 1971 By C. E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Books

BooksTHE TRANSPORTATION ACT OF 1958.

APRIL 1970 By MARTIN L. LINDAHL A.M. '40 -

Books

BooksCOMPARATIVE ANATOMY AND EMBRYOLOGY.

JANUARY 1965 By THOMAS B. ROOS -

Books

BooksWATER FOR THE CITIES.

April 1956 By W.R. WATERMAN