All Snug for the Blow

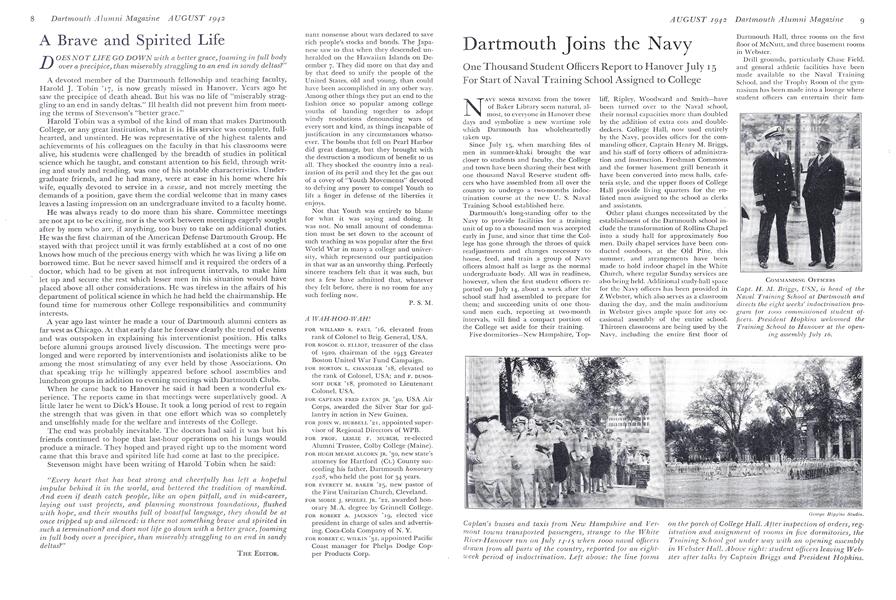

FROM NOW UNTIL THE END OF THE WAR it is obvious that every human concern is going to be more or less tinctured by the war, the colleges of the country quite as surely as any other interest. Indeed the war probably causes more problems to arise for the educational institutions of the United States than for most others in civilian life; problems which relate to the future even more vitally than to the present. One may find all sorts of predictions concerning the future of the American colleges, most of them pessimistic, based less on war-time conditions than on underlying economic trends which were alarming enough before the war broke, but which have been intensified since a thousandfold.

For the moment one may as well push aside the latter aspect of the case with the remark that it will be time to cross that bridge when we come to it. There's quite enough to do now which cannot be evaded. With the creation of an army of men ranging in age from 20 to 45 or so, there is inevitably to be a decimation of the collegiate ranks which normally include the young men of the country from 18 to 22. Some of these will be found unsuitable for active military service and many will be left free to pursue civilian studies. Others will be deferred in their induction to enable them to engage in intensive study along lines leading directly to active life afield or afloat. In other words, the colleges are not going to be entirely deserted, come what may, but at best are going to find their student bodies cut in half, or more than in half, despite all that so-called "streamlining" can do to accommodate existing facilities to greatly diminished numbers.

Meantime there must be faced a drastic curtailment of income, alike from tuition fees and endowments, coupled with the probability that expenditures cannot be decreased, if indeed they are not considerably augmented. Already every college administration has cut every corner that it can, within the limits of reasonable feasibility; but those limits are soon reached and what one prays for is ability to ride out the storm after making all snug for the blow.

THE 1942 ALUMNI FUND

In Dartmouth's case this seems the more certain to be accomplished because of the barometric indications afforded by the current Alumni Fund, which at the moment of writing has yielded a total of $195,000. It would be natural to expect it to fall short of last year's total of $196,000, because in that year there was the added incentive of the observance of President Hopkins' 25th anniversary in office, but is a very close service.

The amazing showing is reassuring. It is evidence (if any were needed) of the unswerving devotion of the Dartmouth alumni, which may be rated the College's most precious and indestructible asset. The efforts of hard-working class agents, under the inspiring leadership of Harvey P. Hood ad '18, chairman, and Albert I. Dickerson '30, executive secretary of the Fund committee, have been spectacularly successful. They provide a mark for future campaigns to strive to reach in the trying years that lie ahead. It is inconceivable that the Alumni Fund shall ever go backward. In the face of the need imposed by war and economic conditions it is imperative that it go forward to new heights. Who shall say that $200,000 is an unreasonable goal for the future?

Outstanding features of this year's campaign clamor for comment which space for the moment precludes—such as the contributions from friends and parents who are not Dartmouth men, and the extraordinarily good showing made by the contributions from men in active service—but these may better be taken up later in detail. For the moment suffice it to say that in making all snug for the blow Dartmouth can rely on the enthusiastic co-operation of all hands.

The Bubble Pacifism

ONE THING MUST HAVE STRUCK the Casual reader of newspapers and magazines, particularly the college magazines, since the shock administered to all Americans at Pearl Harbor, and that is the manifest change of attitude on the part of young men who will do most of the fighting.

The propensity to indulge in flaming outbursts of obstructive pacifism or lachrymose orgies of self-pity would seem to have dwindled toward the vanishing pointthough it would certainly be untrue to say that it has entirely disappeared, and unreasonable to expect it to do so.

There is, however, less to be heard of conscientious objectors, vaporing indig- nant nonsense about wars declared to save rich people's stocks and bonds. The Japanese saw to that when they descended unheralded on the Hawaiian Islands on December 7. They did more on that day and by that deed to unify the people of the United States, old and young, than could have been accomplished in any other way. Among other things they put an end to the fashion once so popular among college youths of banding together to adopt windy resolutions denouncing wars of every sort and kind, as things incapable of justification in any circumstances whatsoever. The bombs that fell on Pearl Harbor did great damage, but they brought with the destruction a modicum of benefit to us all. They shocked the country into a realization of its peril and they let the gas out of a covey of "Youth Movements" devoted to defying any power to compel Youth to lift a finger in defense of the liberties it enjoys.

Not that Youth was entirely to blame for what it was saying and doing. It was not. No small amount of condemnation must be set down to the account of such teaching as was popular after the first World War in many a college and university, which represented our participation in that war as an unworthy thing. Perfectly sincere teachers felt that it was such, but not a few have admitted that, whatever they felt before, there is no room for any such feeling now.

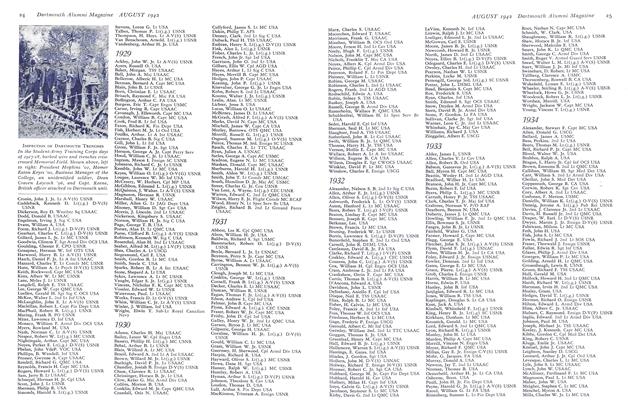

DARTMOUTH REGIMENT ON REVIEW IN WORLD WAR I

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

P. S. M

Article

-

Article

ArticleWINTER FIELD MEET

-

Article

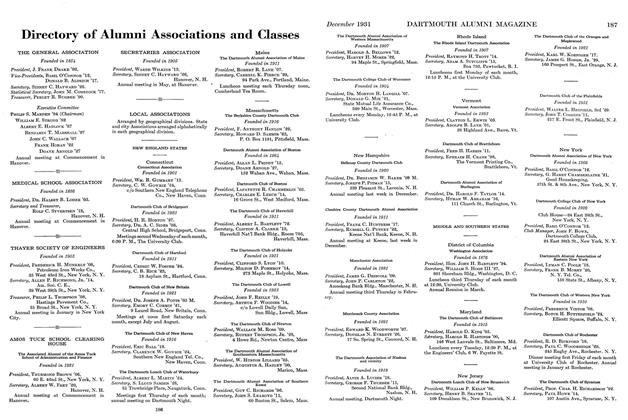

ArticleDirectory of Alumni Associations and Classes

DECEMBER 1931 -

Article

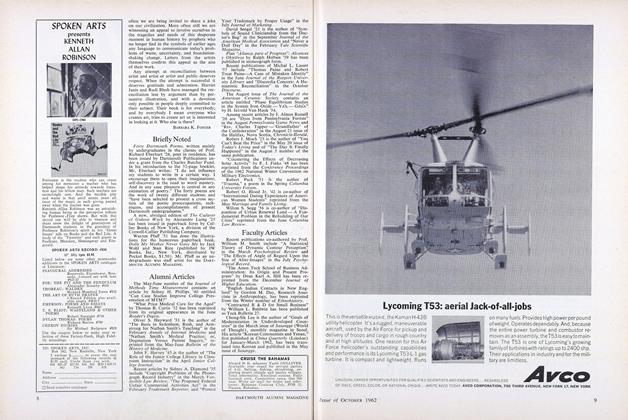

ArticleBriefly Noted

OCTOBER 1962 -

Article

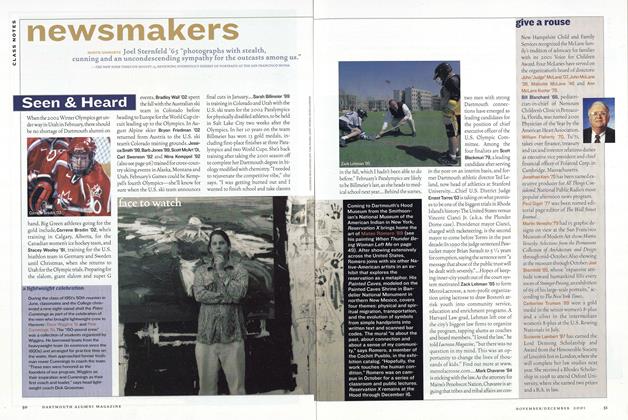

ArticleGive a rouse

Nov/Dec 2001 -

Article

ArticleFraming the Discussion

May/June 2006 By Mark Sweeney '05 -

Article

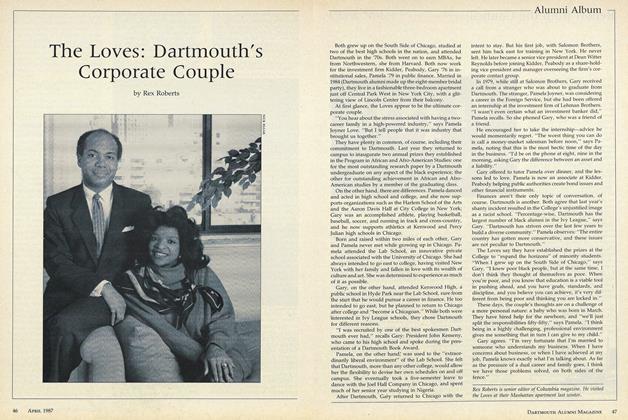

ArticleThe Loves: Dartmouth's Corporate Couple

APRIL • 1987 By Rex Roberts