A Review Confirming Webster's Long-Questioned "Small College" Quotation

MANY SCHOOLBOYS, at least most Dartmouth graduates, know the story that the above words were spoken by Daniel Webster in his peroration in defense of his college before the Supreme Court of the United States. Perhaps they know also that the time was March 10, 1818, and that the occasion was what has become the leading case of Dartmouth College v. Woodward.which began as a terrific local fight between the original Dartmouth College and the legislative Dartmouth University, and no more a "leading case" than the initial wanderings of Mr. Dred Scott. They probably do not know that those words would have been lost to posterity but for the letter of a Yale professor of rhetoric and oratory, written over thirty-four years thereafter.

Did Daniel Webster actually say those words?

Let us examine the evidence of 1818. The argument (and favorable decision) "made" Webster as a constitutional lawyer. That there was a peroration thereto is evident, as will appear; but no contemporary account of these words, or of anything like them, seems to have survived.

First, the newspapers. All but a complete blank. But this is not to be wondered at. The country had not yet learned the power of "nine old men," then seven.' This very Dartmouth College case, establishing, when decided a year later, that no state may pass a law impairing the obligation of any class of contract', was to be the source of much of that power. No special newspaper, no many-volumed "Services," no other legal aids, then broadcasted daily, or at any other interval, to business men or lawyers pronouncements of the Court which might make or break them. Even the official reports of decisions were almost a year behind.

Furthermore, the Capitol at Washington, destroyed by fire in 1814, had not been rebuilt by 1818. The Court held its session that winter, as the Yale professor puts it, "in a mean apartment of moderate size," and the "audience was therefore small, consisting chiefly of legal men.'" There probably weren't any reporters there. Only four newspaper accounts of the argument have been discovered, two in Boston and two in New Hampshire—this last poverty the more remarkable, on account of the violent interest. The lone New Hampshire repercussion of Webster's eloquence of any length is an "Extract to the editor," dated from Washington March 13, 1818, in the New Hampshire Patriot (Concord) of March 24th: The cause was introduced by Mr. Webster in a handsome, elaborate and lengthyargument of several hours.... He closedhis speech with a very pathetic address tothe court, apparently too much affectedwith apprehension of the certain and inevitable ruin of his institution, to expresshimself without tears of sorrow and regret.

Boston was a day ahead of this. The Daily Avertiser of March 23d says: Mr. Webster opened the case in thatclear, perspicuous, forcible and impressivemanner for which he is so much distinguished, and for two or three hours' enchained the Court and the audience withan argument which, for weight of authority, force of reasoning and power of eloquence, has seldom been equalled in thisor any Court.

The Columbian Centinel (Boston) of March 24th is equally brief, vague and dull. I quote it merely for the record: Our friend Webster never made a happier effort. To a most elaborate and lucidargument he united a dignified and pathetic peroration which charmed andmelted his hearers.

Obviously there were no Richard Harding Davises or Mark Sullivans about Washington in those days. It just wasn't the style to send snappy bits like "the horse and buggy age" back to the editor's desk. Let us get on to something better, but noting, as we do get on, that the reading public learned nothing in 1818 about small colleges and those who love them. Unless a decent amount of research has gone wrong, there is nothing more in print in that year.

The closest evidence in time as to what happened in March, 1818, comes from one Salma Hale, a trustee of Dartmouth University, the state-created usurper which had won in the New Hampshire courts (though with a hopeful hint to the college to appeal), and was now the appellee in Washington. Hale was in Washington to assist William Wirt, Attorney-General of the United States, whom the University had called in at the last moment—and who had to sit up "almost the night" to cram his argument, like any schoolboy. (He had argued six cases before the Court since February 2d). "I have been occupied day and night during the week, in searching for facts & documents & am almost exhausted. Mr. Wirt could riot find time to reflect on his argument until Monday eveing" (March 9th), the active Mr. Hale wrote Governor Plumer of New Hampshire on March 12th.5

To return to the question of what Webster said. Writing probably to William Allen, president of the University, on March 10th, Hale is very brief: "Mr. Webster has delivered his speech, which made no little impression." Writing, certainly to Allen, on the nth, he says: "Yesterday Mr. Webster was very disingenuous." On April 2d he tells Allen a bit more:

Mr. Webster did declare that if the decision should be in our favor, the institution would be ruined, as surely said he asthat I now address you. His character, hismanner & artful statement of the case, introduction of political remarks had greatweight on some of the judges.

This is far too general; we are hunting for a specific phrase; but it is all we have in 1818.6 Let us go on to what was printed in Webster's lifetime.

George Ticknor, in his Remarks on theLife and Writings of Daniel Webster, Philadelphia, 1831, gets closer, but not close enough. He says:

As he [Webster] advanced, his heartwarmed to his subject and the occasion.Thoughts and feelings that had grown oldwith his best affections, rose unbidden tohis lips. He remembered that the Institution he was defending was the one wherehis own youth had been nurtured. ...Many betrayed strong agitation, manywere dissolved in tears.

Mr. Justice Story, who, contrary to his usual custom, took no notes (quoted in Wheeler, Daniel Webster, etc., New York, 1905), prepared, probably in 1830, a review of the volume of Webster's speeches then published. This review, which (fortunately) he allowed to remain in manuscript,7 contains the following euphonious ramblings:

And when he came to his peroration,there was in his whole air and manner, inthe fiery flashings of his eye, the darknessof his contracted brow, the sudden andflying flushes of his cheeks, the quiveringand scarcely manageable movements of hislips, in the deep guttural tones of his voice,in the struggles to suppress his own emotions, in the almost convulsive clenchingsof his hands without a seeming consciousness of the act—there was in these thingswhat gave to his oratory an almost superhuman influence. There was solemn grandeur in every thought, mixed up with suchpathetic tenderness and refinement, suchbeautiful allusions to the past, the present,and the future, such a scorn of artifice, andfervor, such an appeal to all the moral andreligious feelings of many, to the lover oflearning and literature, to the persuasiveprecepts of the law, to the reverence forjustice, to all that can exalt the understanding and sensify the heart, that it wasimpossible to listen without increasing astonishment at the profound reaches of thehuman intellect, and without a deep senseof the divinity that stirs within us. Therewas a painful anxiety towards the close.The whole audience had been wrought upto the highest excitement; many were dissolved in tears."

If any fact can be extracted from these expletives, it is that there was no reference to love for a college. The quotation we are hunting is neither moral nor religious, .neither learning nor literature, and has nothing to do with the "persuasive precepts of the law," or justice, or exaltation of the understanding, or profound reaches of the human intellect. If Story had remembered the "small college" incident in 1830, I should have expected a flood of even warmer and more lachrymose adjectives. Perhaps that is what was meant by "pathetic tenderness and refinement," perhaps these were the "scarcely manageable movements of his lips"; but I decline to ratiocinate from an unpublished manuscript of such character.

George S. Hillard, it should be noted, quotes his friend Story much more serenely (A Memorial of Daniel Webster from theCity of Boston, 1852):For the first hour, we listened to himwith perfect astonishment; for the secondhour, with perfect delight; for the thirdhour, with perfect conviction. and does not go on to any fourth hour sensifying the heart, or with convulsive hand clenchings, or flying flushes of the cheeks.

Rufus Choate, who in 1853 gave to the world the Yale professor's letter to him of November 25, 1853, which will appear in a moment as the source of our familiar quotation, had on October 28, 1852, given a memorial address on Webster before the Massachusetts Circuit Court. He then said:

One would love to linger on the scene,when, after a masterly argument of thelaw, carrying, as we may now know, convictionto the general mind of the court, andvindicating and settling for his life time hisplace in that forum, he paused to enterwith these words on his peroration: "Ihave brought my Alma Mater to this presence, that if she must fall, she may fall inrobes, and with dignity" and then brokeforth in that strain of sublime and poeticeloquence, of which we know not muchmore than that, in its progress, Marshall,the intellectual, the self-controlled, the unemotional,announced, visibly, the presence of the unaccustomed enchantment

With this preamble from newspapers, eye-witnesses and friends, let us look for some evidence from Webster himself. The Dartmouth College case made Webster's legal reputation. His argument was repeatedly printed in his lifetime, but you will look in vain for the small college and its lovers in the one-volume gathering of 1830, in the two-volume collection of his speeches and forensic arguments in 1835, in the like three-volume collection of 1848, in his six-volume collected works of 1851, or in any of the other myriad books published by and about him while he was living

Contemporaneously, he does not seem to have immediately appreciated the tears of the apparently exiguous audience, or the "astonishment, delight and conviction" of the bench that Story tells about. Hearsay evidence has Webster characterizing the audience as "small and unsympathetic."" Direct evidence is Webster's letter to President Brown of the college the next day, March 11 th—curiously enough, his only account, on the spot, of his own argument: Our case came on yesterday. I openedthe argument, and occupied almost thewhole sitting in stating the burden of OUTcomplaints.... Mr. Wirt is to follow Mr.Holmes. .. . Mr. Hopkinson is to reply,and will make up for all my deficiencies,which were numerous

A little later Webster woke up to the fact that his argument was perhaps better than he had thought. He decided to print it. Indeed, it was printed three times in 1818," by Webster privately in Boston, by President Brown in Hanover, and by the NewHampshire Patriot, which got hold of one of these private copies. None of the three has any peroration at all. This, of course, is readily explicable in a legal document. As Webster wrote Mason, his New Hampshire associate, April 23, 1818 (emphasis mine):

These copies are and will remain, exceptwhen loaned for a single day, under myown lock and key. They are hastily writtenoff, with much abbreviation, and containlittle else than quotation from the cases. All the nonsense is left out. There is notitle or name to it.13

At this point one Timothy Farrar, of Portsmouth, New Hampshire enters the scene. The Dartmouth College Case was a constant bone of contention in New Hampshire, and the cause was still in the bosom of the law—obviously material for A BOOK.14 There is evidence that at first Webster thought little of the idea, but somehow he came around. Finally he had a large share in its preparation, and was most careful to get it absolutely accurate. And in 1819 (preface dated "August") appeared over a Portsmouth, New Hampshire imprint: Report of the case of theTrustees of Dartmouth College againstWilliam H. Woodward. Argued and Determined in the Superior Court of Judicatureof the State of New-Hampshire, November,181 J, and on error in the Supreme Courtof the United States, February, 1819. ByTimothy Farrar Counsellor at Law, 400 pages in blue boards, uncut, tan boards back, fawn label reading "The Case of Dartmouth College."15

This is the first public printing of Webster's argument. "The arguments have in most instances been taken from the original minutes of their authors, and corrected by themselves," says Farrar's preface. (Heaven knows how he got Wirt's.) We instantly turn to the end of Webster's argument. Has it a peroration? It has. Six lines of Latin—a quotation from Cicero, without a word about smallness or love, or the rest of it.16 And we can guess that Farrar got the Latin from Webster, because the privately printed copy of his argument in the Boston Athenaeum contains the Cicero quotation in Webster's hand—or, rather, so much of it as has escaped the binder's knife. Even for New Hampshire consumption, the moving peroration, and the memorable phrase, are not put into print.

What, then, is the source of the quotation? We must come forward no less than thirty-four years, to the fall of 1852, when Rufus Choate, the great orator who has already delivered one eulogy of Webster, has been asked to give a second at Dartmouth at the next Commencement exercises. The manuscript of that second address is in the Boston Public Library; fortunately for us, the part we are interested in is not in Choate's completely indecipherable handwriting, but is the actual letter he received from Chauncey Allen Good-rich of Yale University, a gentleman, as Choate says in the oration, "with whom I had not the honor of acquaintance."

The beginning of the letter" is pasted face down onto Choate's manuscript, and all that we can now determine is that the date is "Yale College, Nov. 25, 1852," one month after Webster's death, and that Goodrich is sending Choate a copy of his British Eloquence, just published. What induced Goodrich to write we shall never know. Perhaps some report of Choate's Circuit Court speech, perhaps some announcement that Choate was to give the "official" Dartmouth eulogy, perhaps just one orator to another.

One can almost see Choate jump for joy when he got this letter. He had already agreed to give the Dartmouth oration. Less than a month before, at the Circuit Court, he could only give a vague account of the matter; "We know not much more," he says, than that Marshall broke down. "Often since I have heard vague accounts, not much more satisfactory, of the speech and scene," he writes in the pamphlet next to be mentioned. He supposed the peroration to be "lost forever." Here, out of the blue, from a gentleman unknown to him, comes a long, circumstantial, persuasive narrative of an eye-witness, full of moving oratory. Choate inserted almost the entire letter into his oration,18 and it appeared at pp. 35-40 of A Discourse delivered, beforethe Faculty, Students, and Alumni of Dartmouth College, on the day preceding Commencement, July 27, 1853, commemorativeof Daniel Webster, by Rufus Choate, a 100-page pamphlet18 published in tan paper wrappers by James Munroe and Company, Boston and Cambridge, 1853, the first edition of our "familiar quotation."

"ORATORICAL PICNIC"

Yale was obviously just as much interested in the legal question as Dartmouth, and Goodrich, then in his twenty-eighth year, says that he went to Washington chiefly to hear Webster argue this case. It was also more or less his business as a professor of oratory; furthermore, Webster in his New Hampshire (unreported) argument, "had left the whole court-room in tears at the conclusion of his speech,"20 and one can read into Goodrich's letter a hope that Webster would do it again before the august seven at Washington, and a sort of schoolboy determination that, if Webster did, he was not going to miss any such oratorical picnic. His account of the case is familiar—and is the sole source used by all biographers of Webster and Choate, and by such historians as Beveridge and Lodge. The climax comes at p. 38: "Sir, you may destroy this little Institution; it is weak; it is in your hands! I knowit is one of the lesser lights in the literaryhorizon of our country. You may put itout. But if you do so, you must carrythrough your work! You must extinguish,one after the other, all those great tights ofscience which, for more than a century,have thrown their radiance over our land!

"It is, Sir, as I have said, a small College.And yet, there are those who love it

Here the feelings which he had thus farsucceeded in keeping down, broke forth.His lips quivered; his firm cheeks trembledwith emotion; his eyes were filled withtears, his voice choked, and he seemedstruggling to the utmost simply to gain thatmastery over himself which might save himfrom an unmanly burst of feeling. I willnot attempt to give you the few brokenwords in which he went on to speak of hisattachment to the College. The wholeseemed to be mingled with the recollections of father, mother, brother, and allthe trials and privations through which hehad made his way into life. Every one sawthat it was wholly unpremeditated, a pressure on his heart, which sought relief inwords and tears.

This is straightforward reporting, even for a professor of rhetoric and oratory, and only the fact that the report is thirty-four years after the event justifies any examination of its accuracy.

One thing we clearly may not do, and that is to question the truthfulness, in the sense of believing that what one says is true, of the Rev. Chauncey Allen Goodrich. He had just become professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Yale, in 1817, and was offered the presidency of Williams in 1821 at the jittery time when President Moore left the Berkshire Hills to become the first president of Amherst, and took most of the college with him. (Too bad that Goodrich didn't accept; it would improve the story so, for a president of Williams to have given Dartmouth its best quotation.) Goodrich held his oratorical chair until 1839, when he became professor of Pastoral Theology, and so remained in 1852. He compiled works on eloquence, wrote Greek and Latin text-books, edited an enlarged edition of Noah Webster's dictionary, and was responsible for a magazine called the Quarterly Christian Spectator. No one could be more upright or more veracious.

But thirty-four years is a long time to remember accurately, much less to remember verbatim,121 and there is one part of the story that Mr. Goodrich apparently got wrong. At the end of the portion of the speech last quoted, after the "relief of tears," comes Choate's interpolation as to the eager intentness of Court and spectators. The Goodrich letter then goes on that Webster "recovered his composure," "fixed his keen eye" on poor Marshall (who just before, teste Choate—not Goodrich—had "the deep furrows of his cheek expanded with emotion, and eyes suffused with tears"), and concluded with this blast: "Sir, I know not how others may feel,"(glancing at the opponents of the collegebefore him), "but for myself, when I see myalma mater surrounded, like Caesar in thesenate house, by those who are reiteratingstab upon stab, I would not, for this righthand, have her turn to me, and say, Et tu quoque mi fili! And thou too, my son!"

And with this lofty Latin—which, parenthetically, scarcely needed translationsWebster, says Goodrich, "sat down."

Intrinsically, one might doubt if this happened. Choate, in his 1852 speech, says Webster "paused to enter on his peroration" with somewhat similar words (omitting the stabs and the catch-phrase), which at that point would be proper and dignified. Dartmouth was "in the senate house" for judgment. John M. Shirley, in TheDartmouth College Causes, St. Louis, 1879, says Webster "closed" at Exeter before the New Hampshire Court with the same peroration, but cites only "tradition, public prints and old letters" (unspecified). But it would seem almost unthinkable that Webster gave the Shaksperian tag which Goodrich says he did. The deathless words about the college have been spoken. The Court is deeply moved—more so according to Choate's interpolation than according to Goodrich's original. People were in tears. Marshall almost was. It was a good time to stop. No one was then "reiterating stab upon stab," particularly since Webster, as appellant, spoke first. Of what possible legal or histrionic help was it to his argument to say that he speaks on the side he does because he is a loyal Dartmouth man, and not such as the representatives of the University? Merely being a Dartmouth man doesn't win cases. With all deference to orators and constitutional lawyers, such balderdash is no way to end a four-hour speech on a vital question.

Extrinsically, also, we have one strong piece of evidence that Webster stopped where he should have, and never talked stabs and Latin. The man who really took Shakspere as a legal precedent was William Wirt, his opponent, who finished his argument the next day. Going back to the University Trustee, Salma Hale, who had to sit up all night on Monday, March gth, or perhaps the 10th, or both, to cram his distinguished but unprepared counsel, we find him writing on March 12th, presumably to President Allen, since he had written to Governor Plumer the same day:

About two hours ago Mr. Wirt closed avery able argument. His peroration waseloquent. The ghost of Wheelock was introduced, exclaiming to Webster "Et tu,Brute!"

It strains my credulity to have both lawyers use this Shakspere tag. Which did? Wirt's job was to answer Webster's arguments and, even if it was bad taste to do it, one can imagine him, after riddling, or thinking he had riddled, some Websterian point, conjuring up the ghost of Dartmouth's founder, Eleazar Wheelock, crying "Et tu, Brute" that a Dartmouth graduate had made so poor a case.23 The phrase can fit Wirt's argument, and it fits Webster's very badly. And, probabilities aside, we simply must accept the evidence of the man writing two hours after the event as against that of the man writing thirty-four years afterwards.

Of course, in fairness to Goodrich, there is just the possibility that both Webster and Wirt used the Latin tag. The bitterness that raged between the partisans of College and University is today unbelievable; it was New Hampshire's major political issue. And in 1815 there had been the little matter that Webster, then retained and consulted by John Wheelock, Eleazar's son and Allen's father-in-law, as representing the University faction, had walked out on Wheelock a day and a half before an important legislative hearing, and next turned up as counsel for the College. The University people never forgave this—and Webster never had a satisfactory explanation. Now John Wheelock had died in 1817. Salma Hale's cramming might have extended to such local scandals; if it did, and Webster had in fact used this Latin as the phrase a then unassailed Dartmouth would have said if her son hadn't defended her, it was just too pat for Wirt to retort that the real person to say "Et tu, Brute" Was John Wheelock's ghost, contemplating his turncoat lawyer.

All this, however, is not very important. The important thing is that, having caught Mr. Goodrich in one error (if we have), we must stop precisely at that point. "Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus" is one of the most ridiculous proverbs ever used as a basis for serious conclusions. It is particularly silly when applied to a professor of Pastoral Theology who had gone "to Washington chiefly for the sake of hearing Mr. Webster," and whose whole business in 1818 was to attend carefully to great oratory so that he could teach it to little Yale orators-to-be. No, there will always be the lingering doubt that we may not have the quotation exactly as Webster said it, but we should have no doubt whatever that we have Webster's substance. The marvel is that, after complete silence in newspapers, official documents, correspondence, biography and reports of speeches, throughout Webster's long life, the quotation comes to light, thirty-four years after the event, almost through fortuity, from a source that is unimpeach- able. Darmouth College, as, thanks to Webster, it still remains, should erect a tablet to the Reverend Chauncey Allen Goodrich.

STOP PRESS NEWS

I have decided to leave the above just as it was written, as a good example of the dangers o£ incomplete research, particularly by lawyers, too apt to trust to their alleged reasoning power.

After this article had been typed for TheColophon, it became apparent that letters of some of the University faction might be found in a certain distant library. They were there, but they were either immaterial or merely corroboratory. But a chance reference in the papers led to a second library, the New Hampshire State Library, at Concord. Forthwith research, as often. momentarily became exciting. Divine grace had prevented an enthusiast from stubbing his scholastic toe. A piece of evidence appeared which proves that reason, however lucid (to the reasoner), should never stray too far from, facts. In short, a nugget.

Goodrich was right about that "Et tu." Salma Hale was right, also, (He just had to be right—evidence only two hours old.) Both Webster and Wirt said it. Webster was more banal than I thought, and Mr. Hale a better crammer. Salma Hale wrote to William Plumer Jr., son of the governor, on March 24, 1818 (emphasis mine):

... The two speeches of Wirt and Webster, in the college cause, were as good asany I had. ever heard. Webster was unfairin his statement, for which he deserved andreceived castigation, but his argument wasable and his peroration eloquent. He appearedhimself to be much affected—andthe audience was silent as death. He observed that in defending the college he wasdoing his duty—that it should never accusehim of ingratitude—nor address him in the words of the Roman dictator.

Wirt in his peroration spoke of the longperiod during which Wheelock was president—of his many services—of the proof ofhis eloquence just displayed in his pupilof his cruel persecution, dismissal, b deathof a broken heart—he then introduced his ghost exclaiming to Webster "Et tu Brute."

It was a real mental thrill to find that the Reverend Chauncey Allen Goodrich was not even falsus in uno. There is no more any "lingering doubt," as I said in the last paragraph of my article. If Mr. Edward S. Corwin could have had access to the Hale letters, I am quite sure that, on any decent evaluation of evidence, he would not have writen, at p. 163 of John Marshall and theConstitution, 1919: "Whether this extraordinary scene, first described thirty-four years afterward, by a putative witness of it, ever really occurred or not, it is today impossible to say." To me at any rate, at the end of this investigation, the scene described and the words used in Goodrich's letter to Choate of November 25, 1852, should be taken as gospel.

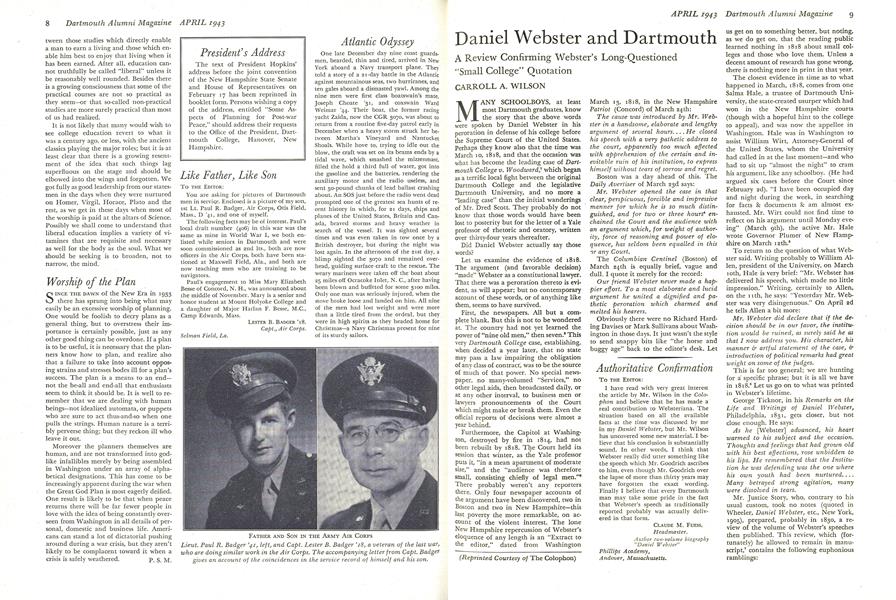

"BLACK DAN" PORTRAIT OF WEBSTER BY FRANCIS ALEXANDER, 1835

(Reprinted Courtesy of The Colophon)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1943 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

April 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

April 1943 By ROBERT DICKGIESSER, J. MOREAU BROWN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1943 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CHARLES A. GRISTEDE -

Article

ArticleFrom the Mailbag

April 1943

Article

-

Article

ArticleADMINISTRATION INCREASES DORMITORY ROOM RATES

May, 1922 -

Article

ArticleA WAH HOO WAH!

May 1944 -

Article

ArticleClass of 2022

SEPTEMBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleFever and Febrifuge

April 1949 By John Hurd '21. -

Article

ArticleScientists in Public Affairs

May 1948 By ROY P. FORSTER -

Article

ArticleThayer School

November 1948 By William P. Kimball '29.