Foreign Correspondent of New Yorker Tells All

THERE IS AN OLD SAYING that a girl can sleep with one man and still not be a trollop, but let a man cover one little war and he's a war correspondent. I am strictly a one-war correspondent, just as a lot of other Dartmouth men are onewar soldiers, and any resemblance between me and Vincent Sheean is purely accidental. Dashing is the pulpwriter's word for war correspondent, but I have never dashed any place except when impelled by extreme fear.

The way I got to be a war correspondent, I think, is that I was working on The NewYorker when the Germans invaded Poland and everybody else on the staff was in drydock in Dr. Riggs' sanitarium or in Hollywood writing a picture. I was writing pieces about jockeys and prizefighters and heels who run nightclubs, and Harold Ross, our esteemed editor, probably thought that would give me a good approach to a war, which is likely to be unrefined too. So I got fitted out with a passport and a Clipper ticket and arrived in Paris early in October, 1939. I stayed in France until Petain and Laval rigged the Armistice, came home, went to England early in the summer of 1941, got back to the United States a month after Pearl Harbor, shuttled back to England in 1942, went from there to Africa and from Casablanca home again after we took Bizerte. I feel like a commuter now; war correspondence is becoming a habitual state.

Pretty soon I hope to begin writing authoritatively. Every day I scan my copy closely for signs of authoritativeness, as a boy looks at his chin in the mirror for the advent of the first hair. I have a numbered card from the War Department that says I am a war correspondent, and who am I to call the War Department a liar? But correspondents are supposed to be either dashing or authoritative, and I am neither. I guess I am in a class by myself, like old Sanborn House, the ruptured dormitory where I nested in 1922-3, brooding above the Bete house and the graveyard. I looked for the old joint when I was up in Hanover in August. It is gone; there is nothing to mark the site. I do not know where they are going to put the tablet to say I lived there.

I am inclined to the thought that the war correspondent has passed the high point of his usefulness in this war, in this resembling the magnetic mine. Before the United States became a belligerent, American correspondents served a purpose beyond the gratification of curiosity. Our despatches pointed out a grave danger, a danger which the ostrich-conks in the United States tried to minimize. Straight news despatches were more effective than editorials could be in marking the advance, the methods, and the purpose to world conquest of the Axis Powers. You didn't have to be a prophet, or even intelligent, in France in May of 1940 to know that the Germans were out to take all, and that it was just a question of whether the United States would fight while there were still allies in the field or wait and go down alone. But it was a hard concept to get across to people at home. People who wanted their comfortable world to continue indefinitely, even though it couldn't (and they included a certain Harvard whodunit writer turned novelist) rather resented the correspondents. It was the old, illogical business of smiting the messenger of ill tidings. I wrote a note for The Twenty-four Hour Notice, the bulletin of my class (fuller explanations dep't: Class of Twenty-four) saying "This is a case of take or be took." It duly appeared, but it looked exotic and hysterical down among the items about how good old Cy Blupp had been made third assistant district personnel manager of the Jam Joint Merchandise Corporation of Fond du Lac. When I got back from Lisbon at the end of June, just after the Petain armistice, people in New York used to wonder why I seemed preoccupied.

So the correspondents' corps shouted in the filthy wilderness, as it says on the College shield, and felt it was doing something useful. But it was the Japs and not the correspondents who got us into the war. That left me and my colleagues at a loss, like a bunch of missionaries whose sales prospects for salvation have all gone Christian at once, leaving them without any excuse for pulling down a salary check. There's only one reason I remain a correspondent now. I've gotten to like this curious trade, which means that I must be going slowly insane. You put up with a lot of red-tape and general nonsense from base-wallahs whom you wouldn't drink over the same stick with in civilian life, and you go to battles that frighten hell out of you, and you make friends with nice kids many of whom you subsequently see hurt, and then you write a couple of pieces. Presumably somebody reads them, although you seldom get to see them in print for six months after their appearance. Then when you come home and somebody in a bar and grill tells you your stuff was swell, it soon turns out he has you mixed up with Drew Middleton or Helen Kirkpatrick.

I am sometimes tempted to stay home and live in a house in Connecticut like Westbrook Pegler, a man of great moral courage, who risks being morally wounded at any moment of the day and always knows exactly what the boys in the foxholes think of any domestic problem. It always turns out that they think his boss is right.

I don't know why I got to thinking of Pegler, but that last paragraph clarifies my theme for me. Now I do know why I like to be a correspondent. When you are a correspondent you never see the newspapers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

October 1943 -

Article

ArticleTHE GIFTED CROSBYS

October 1943 By L. B. RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

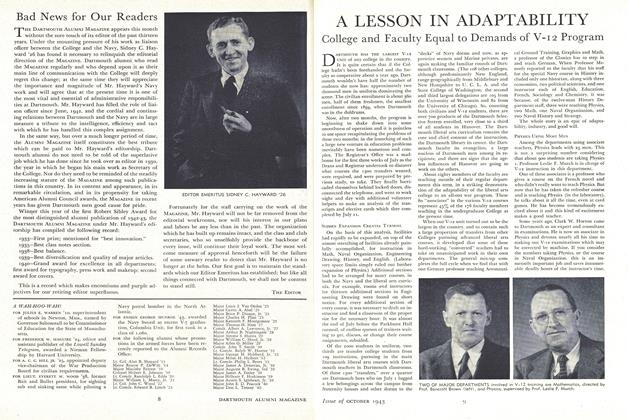

ArticleA LESSON IN ADAPTABILITY

October 1943 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

October 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN, JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1943 By EARNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1943 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS

Article

-

Article

ArticleTRUSTEES HOLD SPRING MEETING

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleSummer Meetings

July 1947 -

Article

ArticleNew Orleans

NOVEMBER 1969 By BRUNSWICK G. DEUTSCH '35 -

Article

ArticleCross Country

OCTOBER 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleGetting Ahead on the Mommytrack

OCTOBER 1990 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleAn Academic Volte-Face

December 1942 By P. S. M.