THE student usually shudders when March rolls around. The slush, mud, treacherous duckboards and dreary days paint a rather dismal picture as the days crawl by toward the mirage of spiing vacation, but this year the College found itself right in the middle of the nation s first 1952 Presidential primary which was held on March 11. As far back as January political interest began to show itself when General Dwight D. Eisenhower's name was placed on the state primary and he admitted that Senator Lodge had given an accurate account of the general tenor of my political convictions and of my Republican voting record." There was indeed much amateur speculation as to what the General actually meant when he declared that "in the absence ... of a clear-cut call to political duty I shall continue to devote my full attention and energies to the performance of the vital task to which I am assigned."

Because of Eisenhower's uncertain status there was little concrete support of the General by any student group, but it was obvious that a large part of the student body favored his candidacy. An Eisenhower-for-President Club was formed in the middle of February, but as yet the appearance of "I Like Ike" buttons is its only sign of activity. Two active Republican aspirants, Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio and Harold E. Stassen, had a lot more to say_even to Dartmouth students.

Senator Taft showed up in nearby Lebanon on March 7 and spent most of his half-hour discussing foreign policy. He soon sensed that a large part of the audience consisted of Dartmouth men and shifted his speech accordingly; he attempted to brush away the Eisenhower myth by declaring: "My views on the various issues are known. But General Eisenhower hasn't taken a stand on a single issue." Some students came away convinced, but generally the Dartmouth men disagreed with his reasoning—especially on foreign policy.

That same evening Mr. Stassen arrived on the college campus, sponsored by the Young Republican Club, and spoke before a packed crowd in Dartmouth Hall. Greeted with sincere applause, the President of the University of Pennsylvania briefly outlined his platform of four planks: (1) a modern gold standard, (2) an honest administration of the national government, (3) a profit-sharing plan for labor and (4) "a new up-to-date foreign policy." He devoted the remainder of his time to receiving questions from the audience which he answered fairly and in detail. A good speaker with a friendly smile, Mr. Stassen was impressive, but his "middle-of-the-road" policy left many a student dissatisfied. Faced with appraising Senator McCarthy and McCarthyism, he would only say that judgment must be postponed until "all the facts were in."

The plank which puzzled many of the students, his plan for a gold-backed dollar, was largely avoided by the former Governor of Minnesota. Frankly, there were many students who were not well-versed enough in economics to challenge his plan for the first gold standard since the days of McKinley, but they did believe that such a radical economic theory deserved more attention than it received. Mr. Stassen stood at the side door shaking hands with each member of the audience after the session was over; political interest on the campus had certainly received a shot in the arm.

The mystery man of the primary stumping campaign was Senator Estes Kefauver, Democrat from Tennessee, who breezed in and out of Hanover twice in three weeks without so much as a day's advance notice. Up to that time the Democrats had remained relatively quiet, confident that Truman would win the Democratic state primary; Kefauver apparently stirred up some enthusiasm in his own quiet, unassuming manner, but you couldn't prove it by the reaction in Hanover. The Senate Crime Investigator drifted into the Inn on February 20 for a short half-hour of questions before dinner. With only a group of approximately thirty listening to him, it was sorely evident that his machine needed wheels.

Senator Kefauver's second visit to Hanover was even more unheralded than the first. On March 6 the Senator slipped into Alumni Gymnasium to watch the last quarter of the Big Green's basketball game with Holy Cross and "visited" briefly with the spectators after the game in the Trophy Room. The Dartmouth mentioned in passing: "The tall Tennessean answered all the questions briefly, but pleasantly, and then asked his audience to help spread the gospel."

As a result of the increased political interest on campus, a group of students formed to consider the possibilities of opening a Students-for-Douglas (William O. Douglas, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court) campaign. Making a detailed examination of his views and his availability as a Presidential candidate, the students hoped to organize an actual group to draft the Associate Justice. Tentative plans for the future, if the students decided to proceed with the movement, would include a petition and information circulated among the rest of the student body, a straw poll to test preferences toward Presidential candidates and perhaps a radio panel in which students would discuss the different candidates.

In fact, it was reassuring to note the generation of a political atmosphere at Dartmouth. Earlier in the year the United World Federalists had disbanded leaving only two semiactive political organizations on the campus—the Young Republicans and the Dartmouth Human Rights Society. There was absolutely no comparison with the political activity which reached its zenith in the late thirties and early forties when such groups as the National Students' League, the American Students' Union and the Junto were in active operation. The present near-vacuum of political interest was explained away by Dean Morse and Dean Neidlinger in two different ways in an article in The Dartmouth last year. Dean Morse believed the present stagnation was due to student indifference toward the general field of politics and a general lethargy in our society today, while Dean Neidlinger felt that students showed as much, if not more, political interest, but that "they just aren't excited by torchlight parades." He stated at the time that radio and the College Lecture Series had taken the place of campus organizations whose main purpose was to sponsor political speakers. "Besides, students today just have too many other things to do." At any rate, it was nice to see a few campaign buttons pinned on lapels, whether they were "I Like Ike" or "Win With Taft."

A case in point emphasizing the current stigma against any new political groups was the red tape which the founders of the Dartmouth Liberal Forum ran into when they attempted to form an organization dedicated to sponsoring "the broad principles of liberalism by encouraging discussion from many points of view," including views "which might not otherwise be heard on the Dartmouth campus." Tentative plans for the formation of such a group were made two weeks before Christmas vacation, but the Forum did not finally receive campus and administrative recognition until the first week in Marcha delay of over ten weeks.

When a proposed constitution was handed to the Dean, he returned it shortly with his approval—provided that several constitutional changes were included: "No official meeting shall be held unless all members of the Forum have been notified in advance by mail and a quorum is present." Protest quickly arose since neither the Young Republican Club nor the Dartmouth Human Rights Society had any such attendance regulations tacked on to their constitutions.

The Undergraduate Council rejected the Dean's suggestion, but it passed, by a close 19-18 vote, an amendment of its own stipulating that the organization would become an official group only when its membership included 20 or more voting members. Actually, this requirement was no hardship for the DLF, but again it was a questionable clause since neither of the other two political groups had membership restrictions added to their constitutions. The Undergraduate Council announced, however, that this 20-man membership requirement would set a precedent for all future organizations at the College—thus hoping to clear up the situation and alleviate any hard feelings. Summing up the situation, The Dartmouth declared:

"One Council member explained to us that the questionable amendment had been tacked on and passed because people were afraid. He further explained that the Council was merely reflecting the political views and emotional tenor of the student body. Ideally, of course, the UGC is a perfectly representative body. It should, however, be something more than that. And that something more is not hard to point to—it is a quality of rising above emotion, a quality of intelligent leadership."

Although politics had diverted the attention of most of the student body, work was still continuing on the Honor System Constitution, proposed by the Academic Committee of the UGC. Following the stipulation by the Faculty that the "reporting clause" in the constitution be changed before being recommended to the student body for approval, the Academic Committee, in conjunction with the Faculty Council's Committee on Examinations, revised the clause to allow "a student to use his own judgment in maintaining the principle of academic honesty." The constitution must now be returned to the Faculty for approval before it goes to the undergraduates for a referendum.

COMMUNITY SPIRIT: Students, townspeople, and faculty helped dig Main Street out on February 24, following the record snowfall. Fraternities, working their men in shifts, played a large part in turning Main St. back to a two-way thoroughfare. The town supplied the trucks; coffee and doughnuts were dispensed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Makes Strong Start in Its 1952 Campaign

April 1952 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1952 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, HOWARD A. STOCK WELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

April 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III, GLENN L. FITKIN JR. -

Article

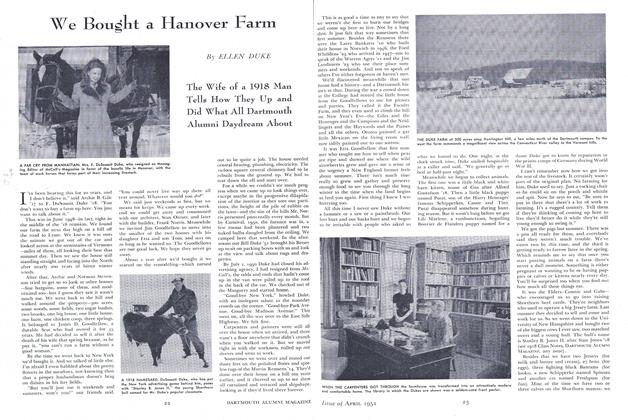

ArticleWe Bought a Hanover Farm

April 1952 By ELLEN DUKE

Conrad S. Carstens '52

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1951 By Conrad S. Carstens '52 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1951 By Conrad S. Carstens '52 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1952 By Conrad S. Carstens '52 -

Article

ArticleFreshman Orientation Studied

January 1952 By Conrad S. Carstens '52 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1952 By Conrad S. Carstens '52 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1952 By CONRAD S. CARSTENS '52