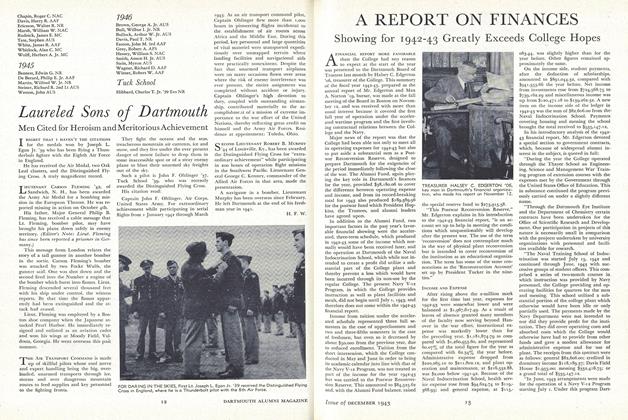

LIEUT. JOHN F. BRISTER '41 KILLED TWO HOURS BEFORE TRANSFER COMES

A BATTALION OF A famous British organization that originally was an American regiment is fighting with Montgomery's Bth Army.

It was before the Revolutionary War that the British Crown organized a regiment of green-shirted Americans to fight Indians. They were known as the 62d Royal American Rifles. Today they are known as the King's Royal Rifles, but, symbolic of their origin, they wear green caps. Anthony Eden was a member during the World War.

I have heard it said that the K. R. R. holds more battle honors than any other British organization save the Royal Marines, and I wouldn't doubt it, for I was attached to them as an ambulance driver of the American Field Service during part of the fighting in Tunisia. I heard them talk of Knightsbridge, Tobruk, Bir Hacheim and Alamein. I saw them die at Akarit. I became as jealous of their reputation as they were. And like any good K. R. R. I wouldn't have been caught dead with a member of the King's Dragoon Guards, who are their ancient rivals. Other Americans felt about them as I did.

KNEW WHAT WAR WAS ABOUT

One such American was a young sixfoot Pennsylvanian. He was a son of "old Dartmouth" who had the foresight to see what this war was about and do something about it. He and several other Americans joined the British Army long before Dec. 7, 1941. Probably because of the history of the K. R. R., the Americans were assigned to that unit. Infantry officers they were.

This is no hero story. Jack Brister, the Pennsylvanian, would have been embarrassed even to have it hinted that there were any heroics in him. It was just that he was restless. Things were happening that he felt were a threat to things that meant something to him. So Brister joined a foreign army. It was that simple.

When I joined the battalion right after the break-through of the Mareth line, Brister was the only American officer in the outfit who had not been killed or wounded. He had been waiting for months to be transferred into the American Army; he'd been in a foreign army a long time and now he wanted to be back with his own people. It wasn't that Brister was unhappy with the British. Far from it. He learned, as all of us did who were with the Bth Army, how simple, warm-hearted and courageous the Tommies and their colonial troops are. And the men in Brister's company simply idolized him. It was enough for them that a young American had come thousands of miles to get into their fight, but Brister has an infectious grin and a quiet sort of courage that the Tommies understood too. "He's fine. And a cheeky bloke, too, 'e is. Takes a dim view of wars, but 'ere 'e is fightin' 'is blinkin' 'eart out."

April passed. Then the battalion received orders that indicated it would be in on the kill. They were going up to the ist Army front at Medjez el Bab. The petrol truck driver in Brister's company was so elated he jumped around like a madman. "Bags and bags of booty," he screamed in a wild frenzy. Brister smiled. They could have their booty. He was waiting for a piece of paper that would tell him he had been transferred. The days went by. Then one day it came through.

It was a couple of hours late; Brister had been killed in action.

Brister could have appreciated the irony of the whole thing. He had got a far different transfer than he had expected, I think. Yet, I wonder; for I often had detected a puzzled look in his eyes. Maybe he was asking himself then why he was still alive when all of his American fellow officers had been killed or wounded. Maybe he suspected he was living on borrowed time.

Somewhere in Pennsylvania today a family is grieving over the loss of a son. But let them know that in the hearts of Englishmen, in the hearts of the men and officers of his battalion, Brister is alive and stalking across the desert with his binoculars bumping against his chest, his hands on his hips, and shouting words of encouragement to his men—Lt. Jack Brister, business.

New York Herald Tribune

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

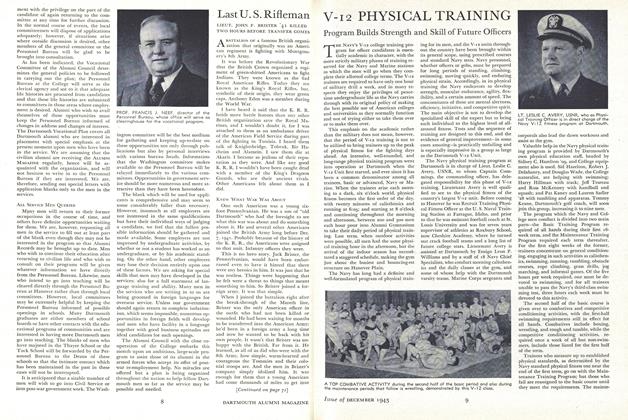

ArticleV-12 PHYSICAL TRAINING

December 1943 By C. E. W. -

Article

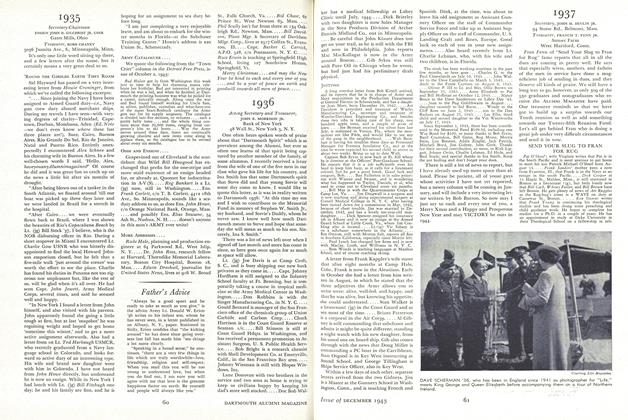

ArticleA REPORT ON FINANCES

December 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

December 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN JR. -

Article

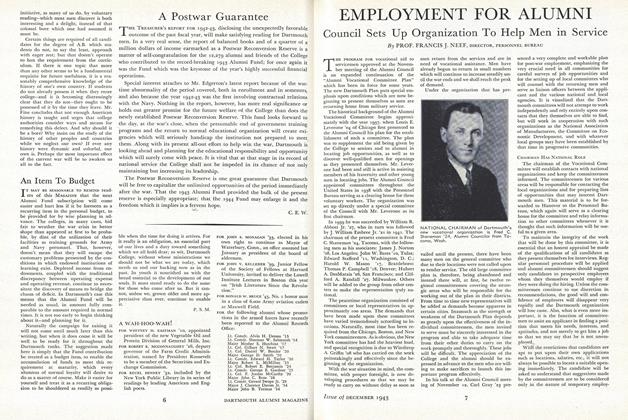

ArticleEMPLOYMENT FOR ALUMNI

December 1943 By PROF. FRANCIS J. NEEF -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

December 1943 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Article

ArticleSHATTUCK OBSERVATORY

December 1943 By L. B. RICHARDSON '00