BILL CUNNINGHAM RECALLS EPISODES FROM LIFE OF FRANK CAVANAUGH '99

THEY'RE ABOUT TO LAUNCH the Frank Cavanaugh picture and some of us who knew and played for the celebrated Iron Major held a sort of memorial service for him last night over a big radio hook-up synchronized with the official release of the film. I haven't seen the picture, but the publicity releases on it say that Pat O'Brien has done a memorable characterization.

Photographs of O'Brien as Cav look like photographs of O'Brien as O'Brien, but that won't make so very much difference to millions. A beauteous young lady billed as Ruth Warrick plays the part of Mrs. Cavanaugh, and they say that the Cavanaugh boys, six of them in the army, had a hard job getting oriented when they visited the studio while the picture was being made. They couldn't quite straighten out the sight of a pretty girl younger than they are playing the part of their mother.

The printed synopsis of the picture seems to say that the script holds pretty faithfully to the old coach's life story with the football emphasis upon his post-war career. A man who never knew him, and who never even saw him, wrote the scenario but he did a faithful job of researching and it could be possible that he did a better job because he never had come in personal contact with the subject he was handling.

Because of this, he could at least see the whole story objectively. Those who knew Cav mostly have the memory of some experience or experiences so deeply burned into them that the rest wouldn't get its honest chance. Cav wasn't a person you met and forgot.

The memories may be funny or serious. Sometimes they are of no particular importance, even, perhaps, in a story of his life, and yet it suddenly strikes the rememberer that they add up to something, that they do belong, and belong hard to any record of the man.

Psychology, for example—morale, they call it in war time. I don't know what he called it, or whether he called it anything. But there was almost nobody who more skillfully knew how to play on the emotions of young men faced with a hard physical chore. The following incidents, for example, add up.

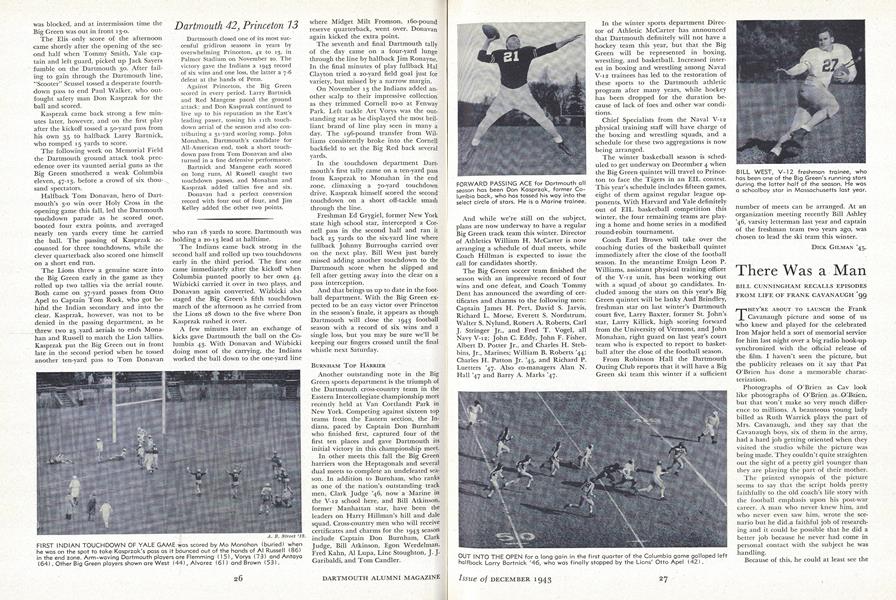

I was a member of the last squad Cavanaugh coached at Dartmouth, and he was keying us for the Princeton game. We were to take the train next morning, and he had assembled us after supper for a last blackboard talk, a final mental rehearsal of plays and plans. We were in what I suppose you'd call the lobby of the big gymnasium. I remember the air outside was clear and frosty cold.

Cav went through the technical part of the talk, and then he digressed into how much this game meant to the prestige of the college, what we owed the college, and what we owed ourselves. Cav always spoke in a deep organ tone.

As he developed this theme, you could have heard a pin drop in the place. Finally he was telling us what the game meant to the alumni, and in proof of this, he drew a big sheaf of telegrams from a brief case and began to read them. Whether on the level or not, we never knew, but nobody thought to question their authenticity then. They came or so he read from all over America, from this alumni association and that from this famous alumnus and that historical athlete.

We were as tense as kids could be as he came to the end. Knuckles were white, faces were strained. It wouldn't have taken much to have broken us into tears. In fact there were tears on some cheeks.

"And now," our coach concluded, "this final message is from that great football enthusiast, Mrs. Frank W. Cavanaugh. It reads, 'You forgot to pay the rent. Please send $25.' That's all, boys. See you tomorrow."

In other words, he took us right up to the line, drew us tight as fiddle strings, and then skillfully snapped the tension with a laugh.

I never thought much about that passing incident until years later when a man told me what seems to me to be one of the great stories of the last war. It was of Cav's coming up to take command of a hard driven outfit that had been holding a bleak and bloody sector for many days without relief. Long overdue for a rest, they were ordered, instead to dig in for some more. Life was all mud and misery and clock-round danger. Cav suddenly arrived as their new commanding officer.

He evidently looked the situation over and it didn't take him long.

"Listen," lie growled at his new command, "you soandsos came over here to die. I'm going to make sure that you get the chance. I don't want to hear any more belly-aching. What do you think you rate? The Waldorf-Astoria? You're going to dig up those guns and you're going to move 'em to the top of that hill. And you're going to hold that hill come hell or high water. And if it's a little too muddy or a little too tough for some of you sissies up there step over into my dugout and maybe I can fix you up a cup of tea."

The man telling the story was a member of this dogged outfit. They had really been fighting like tigers. He said Cavanaugh promptly became the most hated man in France. Some of them even said they'd shoot him if they got an honest chance. All of them expressed the hope that he'd get it first.

But they moved, he said, and hate or no hate, they noted that Cav took for himself the most dangerous dugout. He also took for himself the most dangerous jobs. At regular intervals up with the supplies came generous rations of Cognac. Nobody knew who ordered it, or who was paying for it. A long time afterward, they found out that Cav did. A long time afterward they remembered that for all the hard words, he was gentle with the wounded, certain of their food, that he worked relentlessly for their relief and finally got them out of there.

It was after the war at a reunion that they saw Cav next. He'd been wounded, decorated and had almost died, in the interim, but here he stood upon a platform before those same men again.

"The hardest thing I ever had to do," he said, "was to try to play the bully to great soldiers, and great Americans such as you were in France. The words burned my throat. I didn't dare look you in the eyes for fear you'd see that I was lying. But when I joined you, your nerves were raw, your fighting spirit had lost direction. You'd been left in there too long. You'd taken more than any human beings should be asked to take. You hated the job. You hated the war. You were hating everything in general and nothing in particular. I gambled on the chance that if I could concentrate your hatred upon me, could give you something definite and personal and present to hate, that you'd hate the job less and would proceed to do it better.

"It almost killed me, and I've been waiting all these years to tell you that I didn't mean it, that I couldn't have meant it, that you were really great soldiers and that it was an honor to serve with you, even if I couldn't tell you so at the time. If apologies, gentlemen, aren't too long overdue "

The man said the ovation almost tore the building apart, that Cav cried as they swarmed up to wring his hand, that they finally got him up on their shoulders and I don't know what all.

But, shucks, don't get me started upon the subject of Cav. Whatever the movies did, it would be impossible to get it all. There was a man.

The Boston Herald.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleV-12 PHYSICAL TRAINING

December 1943 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleA REPORT ON FINANCES

December 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

December 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN JR. -

Article

ArticleEMPLOYMENT FOR ALUMNI

December 1943 By PROF. FRANCIS J. NEEF -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

December 1943 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Article

ArticleSHATTUCK OBSERVATORY

December 1943 By L. B. RICHARDSON '00

Bill Cunningham '19

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

June 1935 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleAND WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

December 1935 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

SportsRIGOROUS DISCIPLINE

December 1937 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Sports

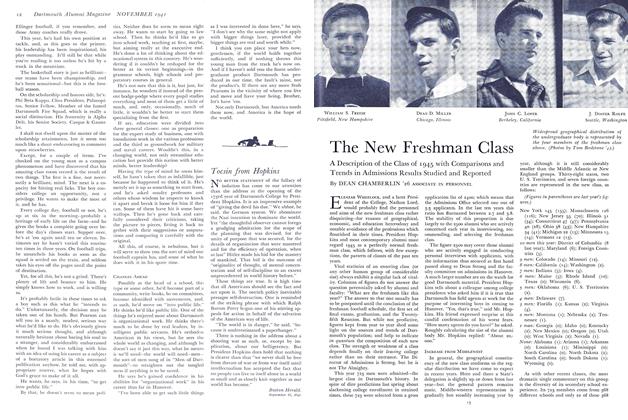

SportsBig Little Green Team

December 1939 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19 -

Article

ArticleDistinctive Student Achievement

November 1941 By BILL CUNNINGHAM '19