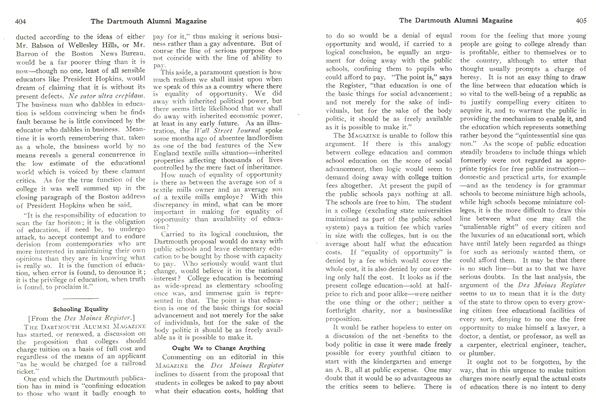

Even those skeptical commentators in Washington, who cannot seem to feel that the American people as yet realize that they are in a war, must admit that if any class of citizens has every reason to realize it the colleges of the country must. The depleted numbers of students and the presence in many cases of troops of young men in active training for Army or Navy must make it impossible to ignore the situation—let alone the curtailed income and the shrunken budgets. Nor is there any complaining, though it is fashionable to assume that the American people bitterly resent every sort of sacrifice that the government demands, as an incident to their blindness. It is doubtful that this official view of the public's attitude does justice to the American public.

The fact is that there has been surprisingly little protest against the demand for rationing of essential articles which in normal times can be bought anywhere as a matter of course. Indeed there has been virtually no protests at all where the public has been convinced that curtailment is vitally necessary to implement the country's war effort. What grousing there is may be ascribed to a failure to show this necessity clearly to those affected. Nothing has hit much harder than the restriction of the use of automobiles; but the obvious necessity of conserving tires and the vastly increased requirement of gasoline as fuel for multitudes of planes, tanks and motorized equipment can be seen by any one. Such things need no explanation. They are self-evident, and by so much the amount of grumbling is reduced to a negligible minimum. It isn't quite the same with other shortages, the imperative need for which is not so apparent. It is with respect to these that official explanations too often appear insufficient, with the result that complaint does arise, more especially where people suspect that restriction is demanded less because of unavoidable scarcity than because of a desire to intensify the public's realization that it is in a war.

It has to be remembered that Americans are not accustomed to being "cracked down" on by bureaucratic officials. Nonetheless, despite that lack of experience, there has been surprisingly little protest, even though it has seemed on occasion that very little effort was made in Washington to mitigate the blow's severity.

There has been some restiveness—and rather reasonable restiveness, too—because of over-elaborate questionnaires and unduly complicated rationing machinery. This disaffection, one suspects, will not manifest itself so much by present grumbling as by wholesale repudiation, when the chance comes, of the idea that "planned economy" has come to stay with us permanently after the war. Before that can be achieved there will need to be more evidence that the eager planners know how to plan. What has been happening during the war has not been well calculated to make the American public fall in love with the idea of having .everything regulated from Washington. Things will be tolerated, without too much complaint when it is a case of winning a war, which would produce a wholesale reaction if carried over into the subsequent peace.

After all, centralized planning of such magnitude has never been a part of that "American way of life" for which we are pouring out blood and treasure. In fact it is the very thing we are striving to avoid. It is disquieting to find so many evidences that our freedom in the future is to be subject to a greatly increased oversight if the devotees of "economic planning" have their way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSulzberger Addresses 1943

February 1943 -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1943 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Article

ArticleColleges Will be Used for Military Training

February 1943 By LLOYD K. NEIDLINGER '23 -

Article

ArticleGovernment War Work

February 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

February 1943 By RICHARD S. JACKSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1943 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleEducation for the Submerged

December 1942 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleNow Comes the Tug

June 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleLet Them Eat Spinach?

August 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Undying

October 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleSi Monumentum Requiris

March 1946 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleFestina Lente

August 1946 By P. S. M.