Men and society pay a price for manliness.

THE FACTS TELL a sobering tale: men live shorter lives than women, perpetrate more violent crimes, and are more apt to spend time in prison. They drink more, have more heart attacks, and succeed more often in committing suicide. These statistics point to one thing, argue English professor Peter Travis and education professor Andrew Garrod: There's a crisis in our culture, created by society's rigid definitions of what it means to be a man.

"Look at how hypermasculine men's role models are," says Travis, pointing to such big on-screen macho men as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, Bruce Willis, and Jean-Claude Van Damme. A "manly" man, says Travis, "isn't allowed to be vulnerable, and believes that it is dangerous to share, open up, and trust." The professors draw on anthropology, literature, and films to demonstrate how different cultures have widely differing "macho" and "feminine" standards of expected male behavior, reinforcing the idea that "masculinity is a social construction," as Travis puts it.

By looking at the "culture of manhood," Travis and Garrod are two of a growing number of academics around the country who are exploring the new field of men's studies. Still in its conceptual stage, the discipline examines the roles that men are expected to adopt through pressure from society, their peers, and themselves in much the same way that women's studies looks at how societies create notions of femininity. Last year Garrod and Travis co-taught an interdisciplinary and cross-cultural course, "The Masculine Mystique: Constructions of Manhood in the Twentieth Century," which focused on the tensions between conflicting ideologies of masculinity and the actualities of men's lives.

Men's Studies? The professors are aware of the irony. "The reaction that most people have is that up until 30 years ago, education always focused almost exclusively on men, so why should there be a resurgence of men, again?" says Travis. "But, that's not what we're talking about." Rather, he and Garrod are attempting to articulate the cultural assumptions that shape and often constrain men's and women's behavior. They ask, for example, why so many boys and men are fascinated by violent sports and war. Sanctioned violence is only part of the answer, according to Travis. "These activities are indoctrinations into a cult of pain and physicality, yet they also give the men a way of bonding physically and emotionally," he says. Think about it: men hugging on a basketball court is a celebrated form of camaraderie, while men hugging on the street is generally taboo. "Men are only allowed to be affectionate with one another in moments of delirium, when they are involved in a sports event, or when they are drunk," adds Garrod.

Is there really a problem, though, if men have an outlet for their aggression and their simultaneous need for intimacy? The answer is yes, according to the professors and, apparently, their students. A few years ago Garrod conducted a longitudinal study of Dartmouth students' adaptation to college life. "What was particularly striking," he says, "was that so many of the men in their interviews mourned the lack of deep, mutual, and lasting relationships with other men. In their first interviews in freshmen fall, a few of these men even asked if they could have a list of all men in the study so that they could 'find a friend.'"

To develop a full conception of why boys end up so differently from girls, Garrod and Travis rely on a broad academic base, ranging from education to literary analysis, sociolinguistics to race and ethnic studies. Examining male and female moral development, for example, they present psychologist Carol Gilligan's theory that males' beliefs are often based on abstract principles of fairness, while females tend to take compassion and the sustenance of relationships into consideration when making moral decisions. Garrod quotes Terrence Real's elaboration of Gilligan's idea: "It isn't that men don't have relational needs. It's that the culture of masculinity straitjackets those needs through the filter of achievement and competition. If the primary paradox for girls and women is about how you maintain full relationality and authentic intimacy when you're not telling the truth because you are frightened to, then the primary paradox for boys and men is how do you achieve full intimacy and relationality when membership is predicated on competition?"

These questions and the course are not just for men. Of the 60 students who took the course last year, half were women. (Another 90 students had to be turned away.) And the course is not a therapy session. Contrary to the approach popularized by authors like iron man Robert Bly, there's no going into the wilderness, beating drums, and getting in touch with inner warriors. Nor does the course call on men to restore their forsaken role as natural leaders, a la the Promise Keepers. In fact, Travis and Garrod argue their aim is quite the opposite. They want students to become more aware that our culture's gender stereotypes can be detrimental to men as well as to women. "Indeed," says Travis, "it is only when both sexes understand the negative and harmful aspects of these stereotypes that they will be free to change them."

Arnold's hypermasculinity backfires in real life.

SUZANNE LEONARD, a former editorial assistant at Fitness, is a grad student in Englishat the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

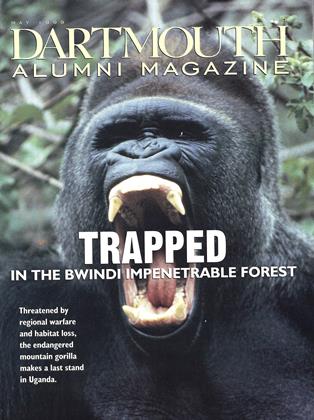

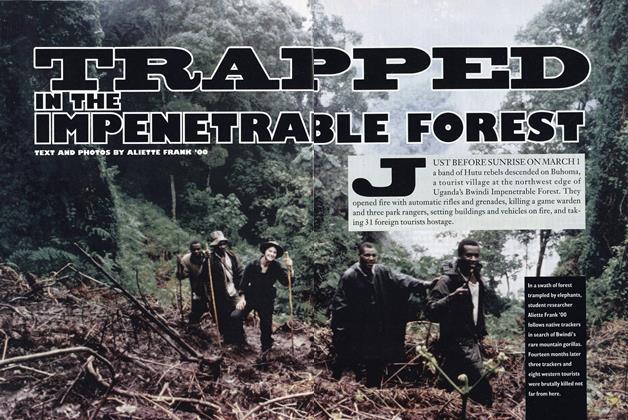

Cover StoryTrapped in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

May 1999 By ALIETTE FRANK '00 -

Feature

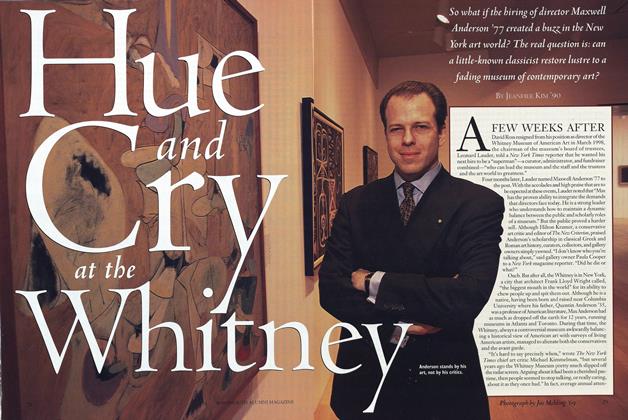

FeatureHue and Cry at the Whitney

May 1999 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Feature

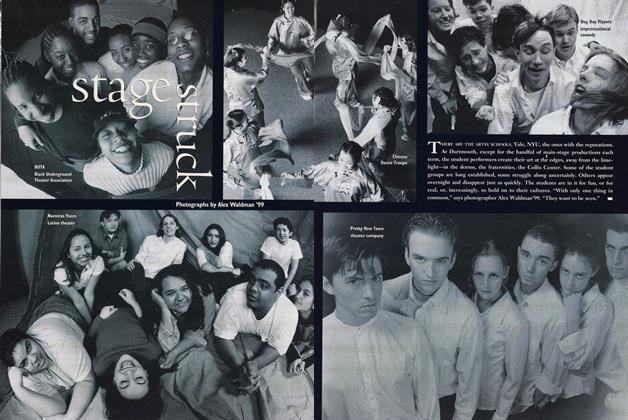

FeatureStage Struck

May 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

May 1999 By Don O'Neill -

Article

ArticleThe Financing Game

May 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleWhat History Can and Cannot Teach

May 1999 By James Wright

Suzanne Leonard '96

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRESIDENT GOMES TO TOWN

June 1995 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleNo Turning Back

September 1995 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleThe Female Majority

December 1995 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleWhat I "Won't Be Doing on My Spring Break

APRIL 1996 By SUZANNE LEONARD '96 -

Article

ArticleCONFIDENCE TAKEN CONFIDENCE BUILT

MARCH 1997 By Suzanne Leonard '96 -

Article

ArticleLooking to Dartmouth

JANUARY 1998 By Suzanne Leonard '96

Article

-

Article

ArticleALUMNI ASSOCIATIONS

JUNE, 1928 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

July 1957 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1942 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleWRESTLING

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

Article1889*

May 1939 By DR. DAVID N. BLAKELY -

Article

ArticleColleges Will be Used for Military Training

February 1943 By LLOYD K. NEIDLINGER '23