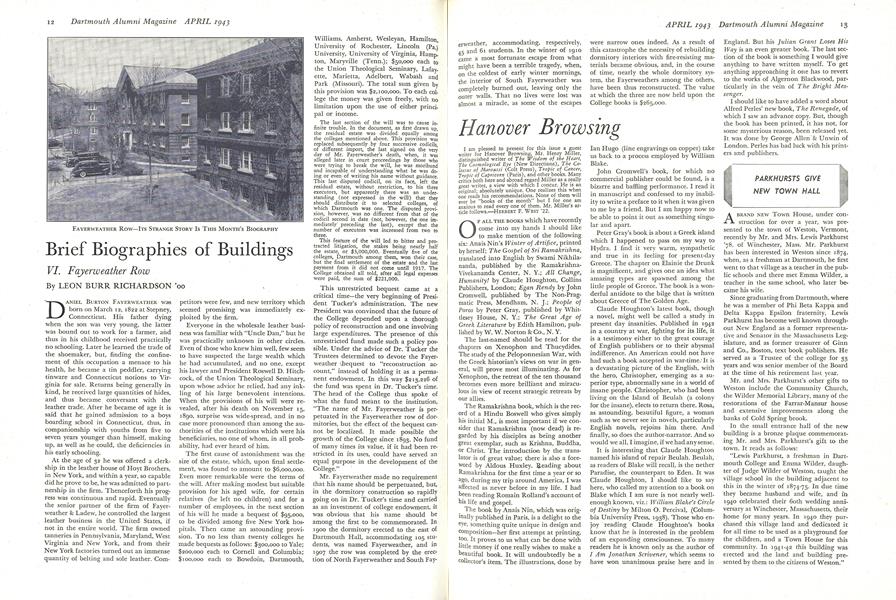

VI. Fayerweather Row

DANIEL BURTON FAYERWEATHER was born on March 12, 1822 at Stepney, Connecticut. His father dying when the son was very young, the latter was bound out to work for a farmer, and thus in his childhood received practically no schooling. Later he learned the trade of the shoemaker, but, finding the confinement of this occupation a menace to his health, he became a tin peddler, carrying tinware and Connecticut notions to Virginia for sale. Returns being generally in kind, he received large quantities of hides, and thus became conversant with the leather trade. After he became of age it is said that he gained admission to a boys boarding school in Connecticut, thus, in companionship with youths from five to seven years younger than himself, making up, as well as he could, the deficiencies in his early schooling.

At the age of 32 he was offered a clerkship in the leather house of Hoyt Brothers, in New York, and within a year, so capable did he prove to be, he was admitted to partnership in the firm. Thenceforth his progress was continuous and rapid. Eventually the senior partner of the firm of Fayerweather & Ladew, he controlled the largest leather business in the United States, if not in the entire world. The firm owned tanneries in Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia and New York, and from their New York factories turned out an immense quantity of belting and sole leather. Competitors were few, and new territory which seemed promising was immediately exploited by the firm.

Everyone in the wholesale leather business was familiar with "Uncle Dan," but he was practically unknown in other circles. Even of those who knew him well, few seem to have suspected the large wealth which he had accumulated, and no one, except his lawyer and President Roswell D. Hitchcock, of the Union Theological Seminary, upon whose advice he relied, had any inkling of his large benevolent intentions. When the provisions of his will were revealed, after his death on November 15, 1890, surprise was wide-spread, and in no case more pronounced than among the authorities of the institutions which were his beneficiaries, no one of whom, in all probability, had ever heard of him.

The first cause of astonishment was the size of the estate, which, upon final settlement, was found to amount to $6,000,000. Even more remarkable were the terms of the will. After making modest but suitable provision for his aged wife, for certain relatives (he left no children) and for a number of employees, in the next section of his will he made a bequest of $95,000, to be divided among five New York hospitals. Then came an astounding provision. To no less than twenty colleges he made bequests as follows: $300,000 to Yale; $200,000 each to Cornell and Columbia; $100,000 each to Bowdoin, Dartmouth, Williams, Amherst, Wesleyan, Hamilton, University of Rochester, Lincoln (Pa.) University, University of Virginia, Hampton, Maryville (Tenn.); $50,000 each to the Union Theological Seminary, Lafayette, Marietta, Adelbert, Wabash and Park (Missouri). The total sum given by this provision was $2,100,000. To each college the money was given freely, with no limitation upon the use of either principal or income.

The last section of the will was to cause infinite trouble. In the document, as first drawn up, the residual estate was divided equally among the colleges mentioned above. This provision was replaced subsequently by four successive codicils, of different import, the last signed on the very day of Mr. Fayerweather's death, when, it was alleged later in court proceedings by those who were trying to break the will, he was moribund and incapable of understanding what he was doing or even of writing his name without guidance. This last disputed codicil, on its face, left the residual estate, without restriction, to his three executors, but apparently there was an understanding (not expressed in the will) that they should distribute it to selected colleges, of which Dartmouth was one. The disputed provision, however, was no different from that of the codicil second in date (not, however, the one immediately preceding the last), except that the number of executors was increased from two to three.

This feature of the will led to bitter and protracted litigation, the stakes being nearly half the estate, or $3,000,000. Eventually five of the colleges, Dartmouth among them, won their case, but the final settlement of the estate and the last payment from it did not come until 1917. The College obtained all told, after all legal expenses were paid, the sum of $221,000.

This unrestricted bequest came at a critical time—the very beginning of President Tucker's administration. The new President was convinced that the future of the College depended upon a thorough policy of reconstruction and one involving large expenditures. The presence of this unrestricted fund made such a policy possible. Under the advice of Dr. Tucker the Trustees determined to devote the Fayerweather bequest to "reconstruction account, " instead of holding it as a permanent endowment. In this way $213,226 of the fund was spent in Dr. Tucker's time. The head of the College thus spoke of what the fund meant to the institution, "The name of Mr. Fayerweather is perpetuated in the Fayerweather row of dormitories, but the effect of the bequest cannot be localized. It made possible the growth of the College since 1893. No fund of many times its value, if it had been restricted in its uses, could have served an equal purpose in the development of the College."

Mr. Fayerweather made no requirement that his name should be perpetuated, but, in the dormitory construction so rapidly going on in Dr. Tucker's time and carried as an investment of college endowment, it was obvious that his name should be among the first to be commemorated. In 1900 the dormitory erected to the east of Dartmouth Hall, accommodating 105 students, was named Fayerweather, and in 1907 the row was completed by the erection of North Fayerweather and South Fayerweather accommodating, respectively, 45 and 61 students. In the winter of 1910 came a most fortunate escape from what might have been a terrible tragedy, when, on the coldest of early winter mornings, the interior of South Fayerweather was completely burned out, leaving only the outer walls. That no lives were lost was almost a miracle, as some of the escapes were narrow ones indeed. As a result of this catastrophe the necessity of rebuilding dormitory interiors with fire-resisting materials became obvious, and, in the course of time, nearly the whole dormitory system, the Fayerweathers among the others, have been thus reconstructed. The value at which the three are now held upon the College books is $265,000.

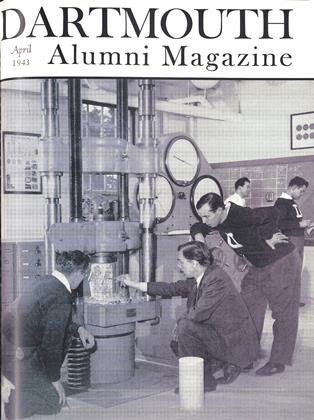

FAYERWEATHER ROW—ITS STRANGE STORY IS THIS MONTH'S BIOGRAPHY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDaniel Webster and Dartmouth

April 1943 By CARROLL A. WILSON -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1943 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth War Directory

April 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

April 1943 By ROBERT DICKGIESSER, J. MOREAU BROWN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1943 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CHARLES A. GRISTEDE

LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00

-

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

December 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleIV. Wilson Hall

January 1943 By Leon Burr Richardson '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

May 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

June 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

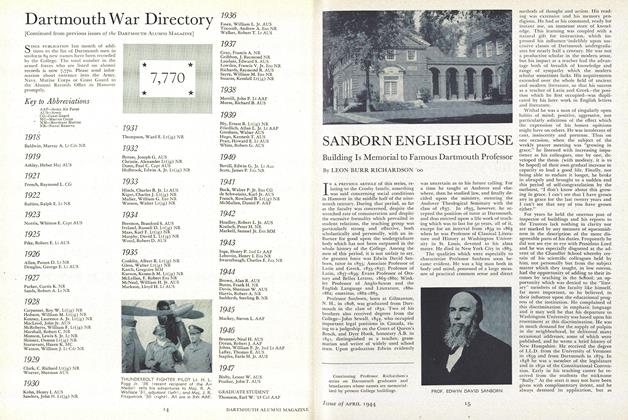

ArticleSANBORN ENGLISH HOUSE

April 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleSTREETER HALL

May 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00