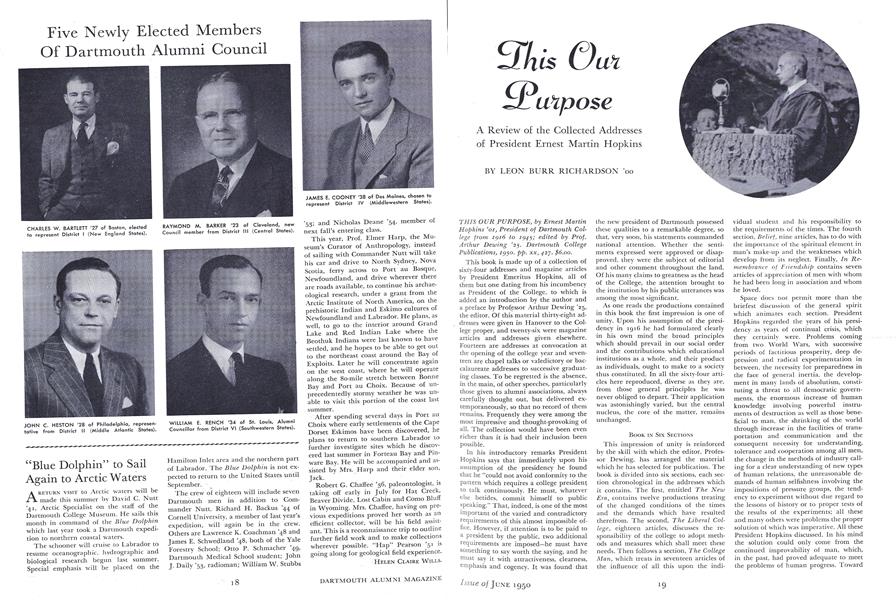

A Review of the Collected Addresses of President Ernest Martin Hopkins

THIS OUR PURPOSE, by Ernest MartinHopkins '01, President of Dartmouth Collegefrom 1916 to 1945; edited by Prof.Arthur Dewing '25. Dartmouth CollegePublications, 1950. pp. xx, 427. $6.00.

This book is made up of a collection of sixty-four addresses and magazine articles by President Emeritus Hopkins, all of them but one dating from his incumbency as President of the College, to which is added an introduction by the author and a preface by Professor Arthur Dewing '25, the editor. Of this material thirty-eight addresses were given in Hanover to the College proper, and twenty-six were magazine articles and addresses given elsewhere. Fourteen are addresses at convocation at the opening of the college year and seventeen are chapel talks or valedictory or baccalaureate addresses to successive graduating classes. To be regretted is the absence, in the main, of other speeches, particularly those given to alumni associations, always carefully thought out, but delivered extemporaneously, so that no record of them remains. Frequently they were among the most impressive and thought-provoking of all. The collection would have been even richer than it is had their inclusion been possible.

In his introductory remarks President Hopkins says that immediately upon his assumption of the presidency he found that he "could not avoid conformity to the pattern which requires a college president to talk continuously. He must, whatever else betides, commit himself to public speaking." That, indeed, is one of the most important of the varied and contradictory requirements of this almost impossible office. However, if attention is to be paid to a president by the public, two additional requirements are imposed—he must have something to say worth the saying, and he must say it with attractiveness, clearness, emphasis and cogency. It was found that the new president of Dartmouth possessed these qualities to a remarkable degree, so that, very soon, his statements commanded national attention. Whether the sentiments expressed were approved or disapproved, they were the subject of editorial and other comment throughout the land. Of his many claims to greatness as the head of the College, the attention brought to the institution by his public utterances was among the most significant.

As one reads the productions contained in this book the first impression is one of unity. Upon his assumption of the presidency in 1916 he had formulated clearly in his own mind the broad principles which should prevail in our social order and the contributions which educational institutions as a whole, and their product as individuals, ought to make to a society thus constituted. In all the sixty-four articles here reproduced, diverse as they are, from those general principles he was never obliged to depart. Their application was astonishingly varied, but the central nucleus, the core of the matter, remains unchanged.

BOOK IN SIX SECTIONS

This impression of unity is reinforced by the skill with which the editor. Professor Dewing, has arranged the material which he has selected for publication. The book is divided into six sections, each section chronological in the addresses which it contains. The first, entitled The NewEray contains twelve productions treating of the changed conditions of the times and the demands which have resulted therefrom. The second, The Liberal College, eighteen articles, discusses the responsibility of the college to adopt methods and measures which shall meet these needs. Then follows a section, The CollegeMan, which treats in seventeen articles of the influence of all this upon the individual tudent and his responsibility to the requirements of the times. The fourth section, Belief, nine articles, has to do with the importance of the spiritual element in man's make-up and the weaknesses which develop from its neglect. Finally, In Remembranceof Friendship contains seven articles of appreciation of men with whom he had been long in association and whom he loved.

Space does not permit more than the briefest discussion of the general spirit which animates each section. President Hopkins regarded the years of his presidency as years of continual crisis, which they certainly were. Problems coming from two World Wars, with successive periods of factitious prosperity, deep depression and radical experimentation in between, the necessity for preparedness in the face of general inertia, the development in many lands of absolutism, constituting a threat to all democratic governments, the enormous increase of human knowledge involving powerful instruments of destruction as well as those beneficial to man, the shrinking of the world through increase in the facilities of transportation and communication and the consequent necessity for understanding, tolerance and cooperation among all men, the change in the methods of industry calling for a clear understanding of new types of human relations, the unreasonable demands of human selfishness involving the impositions of pressure groups, the tendency to experiment without due regard to the lessons of history or to proper tests of the results of the experiments; all these and many others were problems the proper solution of which was imperative. All these President Hopkins discussed. In his mind the solution could only come from the continued improvability of man, which, in the past, had proved adequate to meet the problems of human progress. Toward that improvability the educational institutions of the country have, according to his way of thinking, the most pressing and direct responsibility.

The second section, The Liberal College, the most controversial of all, treats of the response of the college to this responsibility. During a period when that institution was under attack from a great variety of sources, President Hopkins was stalwart in its defense. He lauded highly the various forms of educational approach prevalent in this country—graduate school, professional school, trade school and many others—as indispensable each in its own way and for its own purpose. But, except for the liberal college, none of them is adequate for the development in the student of that wide and broad training which makes him effective in the social order as a whole. Scholarship is highly important, professional competence is indispensable, specialization is necessary if the work of the world is to be done. Each in its place should be encouraged in the college. But the impact of the institution, 60% of whose students reach in it the terminal point in their education, is more far-reaching than that. The development of its students should be along broader lines. It is the responsibility of the college first to select its student material as being intellectually capable of assimilating the education that it gives. Upon them it should make exacting intellectual demands. But it should also cultivate in the individual all aspects of his personality with equal care; physical, emotional, spiritual, as well as mental. It should expose him to the fair presentation of many theories of common concern, however unpopular in various quarters some of them may be. It should develop his sense of responsibility, based on the ingrained habit of meditation and thoughtfulness. He should be trained to form definite opinions for himself, but these opinions should always be subject to the impact of new ideas. The college should exert itself to encourage effective leadership, but, even more important so far as numbers are concerned, to turn out men thoughtful enough and public spirited enough to select proper leaders to follow. Summing it all up, as President Hopkins did in one of his last addresses, that at the Bowdoin Sesquicentennial in 1944, the aim of the college may be summarized in the words of the biblical proverb of old, "With all thy getting, get understanding."

The third section, The College Man, consists largely of appeals to the individual student to assume the responsibility of utilizing to the full the facilities afforded by the College for the accomplishment of the results set forth above. The following section, entitled Belief, is made up for the most part of valedictory and baccalaureate addresses, and emphasizes the high importance of the spiritual aspect of man's existence. It continues admirably, although in a different manner, the high effectiveness of the vesper talks of Dr. Tucker, so vital a part of the education of the students of the college during all his presidency. Then comes a series of appreciations, discriminating despite their emotional content, of some of his friends and the friends of Dartmouth who have passed beyond; Frank Sherwin Streeter, Richard Drew Hall, William Jewett Tucker, Irving Joseph French, Eugene Francis Clark, Nelson Pierce Brown, as well as a memorial address to the nine Dartmouth men who lost their lives in the carbon monoxide tragedy of 1934. Finally, by itself, is placed the very brief, but deeply moving address to the trustees and faculty as he passed over the office he had held so long to his successor, President Dickey, in 1945.

Truly President Hopkins had attained for himself in full measure the goal which he set for the graduates of the Collegethe power of understanding. But he had something much rarer than that; the gift of wisdom. There is not much in these published papers that is not fully applicable to the crisis of today; there are not many of the remedies which he advances which could not be applied effectively at the present time to the problems which press for solution.

In a way the reader may experience a sense of frustration in the perusal of these addresses. We are anxious to know how it all came out. Of course the stream of history is continuous and does not "come out" at any particular time. But, none the less, we may hope that President Hopkins may find the leisure at some future time to write, supplementing the present volume which all Dartmouth men will wish to own, a final account which sums up the experiences of his active and useful life.

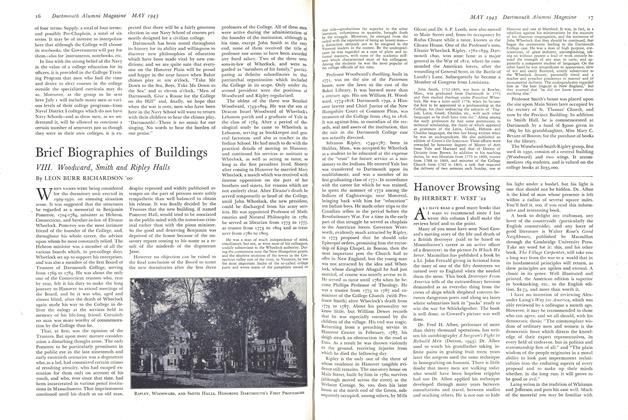

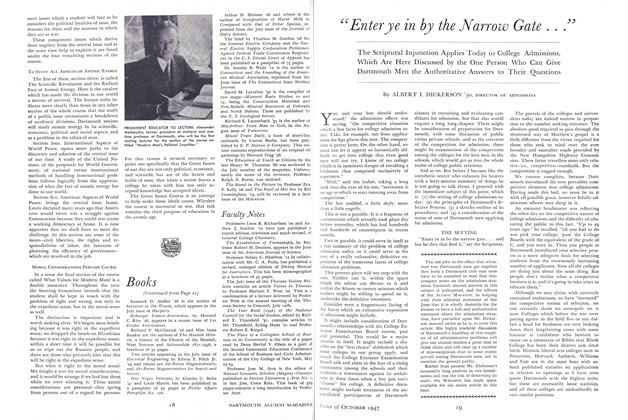

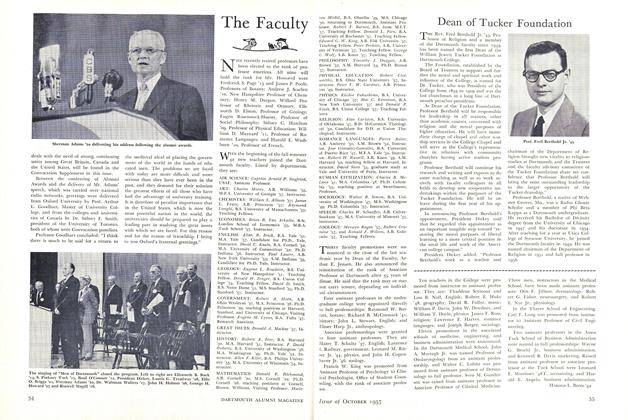

PRESIDENT EMERITUS HOPKINS, who recently resigned as president of National Life Insurance Co. of Montpelier, Vt„ to become chairman of the board, sits for a new portrait to hang in the room where paintings of earlier company presidents also appear. The artist is Julius Katzieff, who has done a number of Dartmouth portraits, including President Tucker and George F. Baker, donor of Baker Library.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

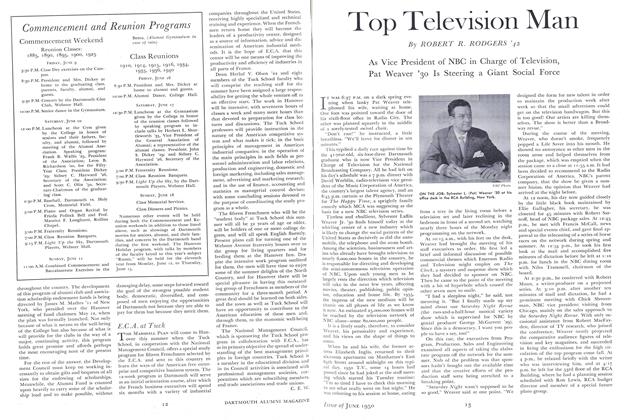

ArticleTop Television Man

June 1950 By ROBERT R. RODGERS '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1950 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1950 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

June 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

June 1950 By CMDR. F. STIRLING WILSON, DANIEL S. DINSMOOR, WILLIAM H. MCKENZIE

LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00

-

Article

ArticleUseless Dartmouth Information

February 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

October 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

November 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

December 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

May 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleSANBORN ENGLISH HOUSE

April 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00

Article

-

Article

ArticleFaculty Notes

October 1947 -

Article

ArticleLeaving Big Blue

September 1995 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth 34, Brown 0

November 1961 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1951 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleAtlanta

February 1960 By WALLACE ROGERS II -

Article

ArticlePraises Pres. Hopkins' Address

MARCH, 1928 By WILLIAM STEARNS DAVIS.