Building Is Memorial to Famous Dartmouth Professor

IN A PREVIOUS ARTICLE of this series, relating to the Crosby family, something was said concerning social conditions in Hanover in the middle half of the nineteenth century. During that period, so far as the faculty was concerned, despite the wretched rate of remuneration and despite the excessive formality which prevailed in student relations, the teaching group was particularly strong _ and effective, both scholastically and personally, with an influence for good upon the undergraduate body which has not been surpassed in the whole history of the College. Among the men of this period, it is not unfair to say, the greatest force was Edwin David Sanborn, tutor in 1835; Associate Professor of Latin and Greek, 1835-1837; Professor of Latin, 1837-1859; Evans Professor of Oratory and Belles Lettres, 1863-1880; Winkley Professor of Anglo-Saxon and the English Language and Literature, 1880-1883; emeritus, 1883-1885.

Professor Sanborn, born at Gilmanton, N. H., in 1808, was graduated from Dartmouth in the class of 1832. Two of his brothers also received degrees from the College—John Sewall, 1842, who occupied important legal positions in Canada, rising to a judgeship on the Court of Queen's Bench, and Dyer Hook, honorary A.B. in 1841, distinguished as a teacher, grammarian and writer of widely used school texts. Upon graduation Edwin evidently was uncertain as to his future calling. For a time he taught at Andover and elsewhere, then he studied law, and finally decided upon the ministry, entering the Andover Theological Seminary with the class of 1837. In 1835, however, he accepted the position of tutor at Dartmouth, and thus entered upon a life work of teach- ing which was to last for 50 years, all of it, except for an interval from 1859 to 1863 when he was Professor of Classical Literature and History at Washington University in St. Louis, devoted to his alma mater. He died in New York City in 1885.

The qualities which were especially to characterize Professor Sanborn soon became evident. He was a big man both in body and mind, possessed of a large measure of practical common sense and direct methods of thought and action. His reading was extensive and his memory prodigious. He had at his command, ready for instant use, an immense store of knowledge. This learning was coupled with a natural gift for instruction, which impressed his influence'indelibly upon successive classes of Dartmouth undergraduates for nearly half a century. He was not a productive scholar in the modern sense, but his impact as a teacher had the advantage both of breadth of knowledge and range of sympathy which the modern scholar sometimes lacks. His acquirements extended over the whole field of ancient and modern literature, so that his success as a teacher of Latin and Greek—the position which he first occupied—was duplic ated by his later work in English letters and literature.

Withal he was a man of singularly open habits of mind; positive, aggressive, not particularly solicitous of the effect which the expression of his honest opinions might have on others. He was intolerant of cant, insincerity and pretense. Thus on one occasion, when the subject of the weekly prayer meeting was "growing in grace," he listened with increasing impatience as his colleagues, one by one, developed the thesis (with modesty, it is to be hoped) of their own gradual increase in capacity to lead a good life. Finally, not being able to endure it longer, he broke in abruptly and brought to a sudden end this period of self-congratulation by the outburst, "I don't know about this growing in grace. I can't see that I have grown any in grace for the last twenty years and I can't see that any of you have grown either."

For years he held the onerous post of inspector of buildings and his reports to the Trustees lack nothing in clarity nor are marked by any measure of squeamishness in the description of the more disagreeable parts of his duties. Frequently he did not see eye to eye with President Lord and he was especially disgusted at the advent of the Chandler School whereby certain of his scientific colleagues held by him, not personally but from the subject matter which they taught, in low esteem, had the opportunity of adding to their inc omes by teaching in the School; an opportunity which was denied to the "literary" members of the faculty like himself, far more important, so he believed, in their influence upon the educational progress of the institution. He complained of this discrimination in emphatic language and it may well be that his departure to Washington University was based upon his resentment at this discrimination. He was in much demand for the supply of pulpits in the neighborhood, he delivered many occasional addresses, some of which were published, and he wrote a brief history of New Hampshire. He received the degree of LL.D. from the University of Vermont in 1859 and from Dartmouth in 1879. In 1848 he was a member of the legislature and in 1850 of the Constitutional Convention. Early in his teaching career he rec eived from the students the nickname "Bully." At the start it may not have been given with complimentary intent, and he always detested its application, but as years went on it became a term which, in the minds oF those who used it, indicated the respect and real affection in which the sturdy professor was held by the whole undergraduate body.

Professor Sanborn's home in Hanover was the large house to the west of the Green, built in the first decade of the nineteenth century by Dr. Cyrus Perkins, and afterwards occupied in turn by Presidents Brown and Tyler and Professor Oliver. Externally it was not an especially attractive dwelling but internally it was spacious enough. Particularly striking was the study of the professor, adorned by pictorial wall paper illustrating the Bay of Naples, so that his daughter Kate always maintained that she was born in the shadow of Vesuvius. As in the homes of the other professors, the living here was adequate, but simple; perhaps even primitive by modern standards. Professorial income had to be supplemented by the yield of a large garden, cultivated by professorial hands; domestic animals—at least a cow and pigswere a necessary part of family possessions; in the fall supplies of provisions of home production—animal and vegetable—were stored away, as well as some forty or fifty cords of wood, prepared for fireplace or stove. Many years later, Edwin, a son of the family, from his own bitter experience was inclined to place the peripatetic wood-sawing machine, animated by a horse power, as the greatest invention of the age, although he had ruefully to admit that the privilege of splitting and piling the wood by hand still remained unaffected by modern progress. Winters brought a succession of frozen pipes, burning chimneys and shivering nights spent in unheated bedrooms. But there was another side to the picture. The atmosphere was one of refinement and culture. Education began at home early and under the best of auspices. Distinguished visitors, coming to Hanover to lecture or for other purposes, in many cases were the guests of the Sanborns; if not, they always called on the distinguished professor to "pay their respects." It was under such favorable conditions that the Sanborn children were reared.

In 1837 Professor Sanborn married as his first wife Mary Ann, daughter of Ezekiel Webster (brother of Daniel). She died in 1864. A frequent member of the household was her mother, left a widow as a young woman in her twenties, who lived to the advanced age of 96. Mrs. Webster was a woman of remarkable personal charm, who, her grandson reports, had rec eived in her young widowhood as many as twenty offers of marriage all of which she declined, "preferring to remain the widow of Ezekiel Webster than to be the wife of any other man." Her influence on the growing Sanborn children, and, for that matter, on the whole Hanover community was profound.

Two daughters and a son of Professor Sanborn grew to mature years. Mary, later Mrs. Babcock, although her mental capacity was high, was a quiet character, content with a domestic life. Kate (Katherine Abbott) 1837-1917, on the other hand was restless, active and ambitious. A stirring and somewhat unruly child, she absorbed eagerly from her father the instruction coming from his stores of learning, and, in addition, listened avidly to the conversation of the distinguished visitors to the Sanborn home. Very early she began to write, and successfully, so far as publication was concerned. For a time she was an acceptable teacher, among other places as a member of the early faculty of Smith College. All her life she was in steady demand as a lecturer. Possessed of a keen sense of humor, her books abound in clever turns and apt citations, although impaired perhaps by a tendency toward redundancy and lack of logical order. Her true story, Adopting an Abandoned Farm, 1891, and its successor, Abandoning anAdopted Farm, 1894, attained the status of best sellers. Her memory is perpetuated in Hanover by the Kate Sanborn Room in the College Church.

The son, Edwin Webster Sanborn, 18571928, entered college in the class of 1877, but by ill health was prevented from graduating until 1878. After a period of teaching he studied law at Columbia and was admitted to the New York bar in 1882. Carrying on a general practice with a partner for some ten years, he then became associated with the American Agricultural Chemical Company until his retirement in 1913. All his life he was compelled to struggle with ill health, so that he spent much of his time out-of-doors, travelling widely and being especially devoted to fishing, of which art he became an expert. He also wrote many articles for the nature magazines and was the author of one novel, People at Pisgah, which caused something of a scandal in his native town because of the resemblance of some of the characters to former denizens of that community. He had an abundant sense of humor, often whimsical in character, and was an admirable after-dinner speaker. For the last fifteen years of his life he was the victim of a hopeless, progressively increasing malady which finally removed him from all contact with his friends, but through it all he preserved his courage and sense of poise. He died on shipboard, on his way to San Francisco, in 1928.

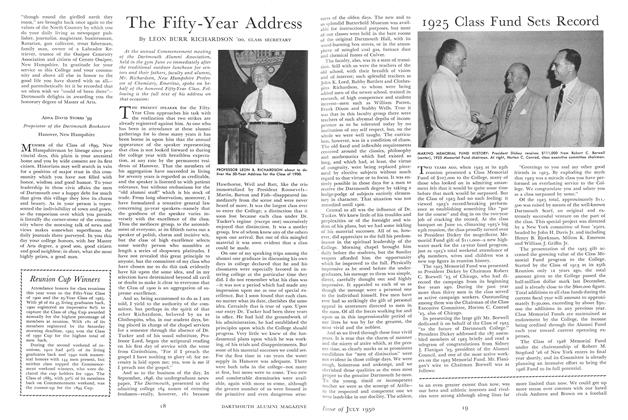

At the time of his retirement Professor Sanborn's financial condition was precarious in the extreme. In the college archives is a moving letter from his daughter Kate appealing to Trustee Quint that the College make some financial provision for her father and protesting against the brusque manner in which a similar appeal had been rejected by President Bartlett. As a matter of fact, somewhat later relief was in a measure afforded by the provision in the gift of the chapel by Mr. Rollins that an annuity of $5OO should be provided by the College for Professor Sanborn. He did not live long to enjoy it. In later years the fortunes of the Sanborn family notably improved. Kate apparently received a legacy of considerable size, which upon her death in 1917 she left to her brother. This, added to his own accumulations and with careful management of the whole, finally increased to a real fortune. Upon his death the greater part of it was bequeathed to the College, amounting to about $1,655,000. According to the will a sum not to exceed $400,000 was set aside for the erection of the English House, $lO,OOO was given to the Outing Club, and the remainder was to constitute a fund the income of which should be used for the purchase of books for the library.

Accordingly in 1929-1930 the Sanborn English House was built at an expense of $344,000. The donor stated that his father was "a living library of learning, but at his best when pouring forth his fund of information in informal talks." It was to preserve this spirit that provision was made for studies (not offices) for members of the English Department, each fitted up and comfortably furnished according to the taste of the occupant. In these studies individual conferences with students, singly or in small groups, could be held in a homelike atmosphere. No recitation or class rooms were made a part of the project but an adequate library for advanced English students was supplied, as well as suitable provision for assembly purposes. The study of the old professor, the scenic wall paper of the original transferred to it, was reproduced. The fund for the purchase of books, the principal amounting to $1,400,000, since its receipt has made the Dartmouth library completely adequate for the purpose it is designed to serve. The Sanborn bequest is brought home to each reader by book plates containing a portrait of the professor, inserted in all books purchased from the fund. Certainly no college teacher has been the beneficiary of a more adequate memorial nor one more fully deserved.

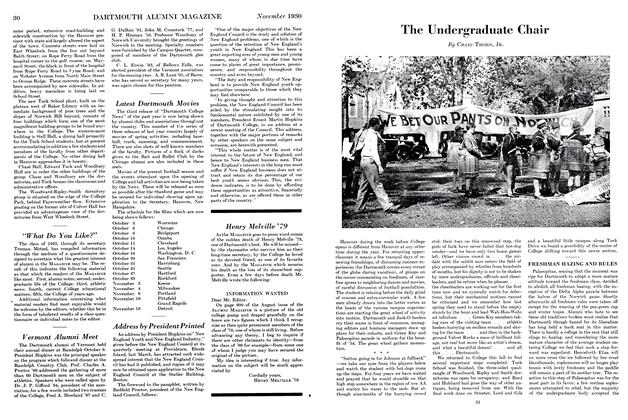

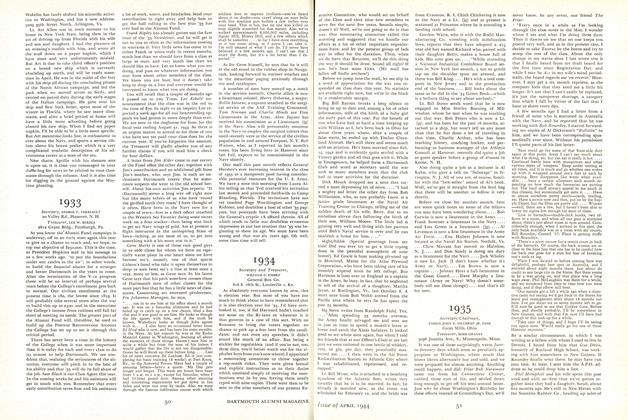

PROF. EDWIN DAVID SANBORN

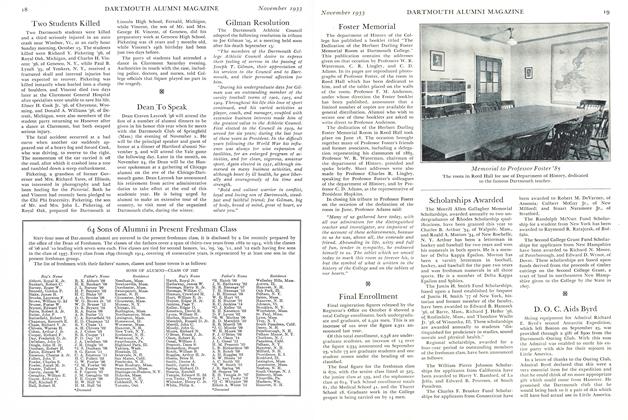

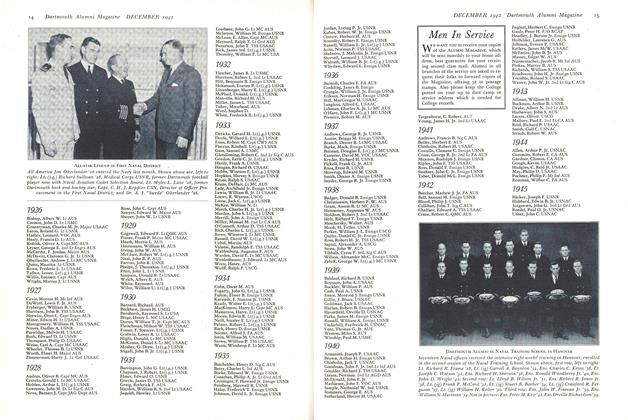

EDWIN WEBSTER SANBORN '78, donor of Sanborn English House and the million-dollar Sanborn Library Fund in memory of his distinguished Dartmouth father.

Continuing Professor Richardson's series on Dartmouth graduates and benefactors whose names are memorialized by present College buildings.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE MEN IN POLITICS

April 1944 By DAYTON D. McKEAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

April 1944 By ENSIGN JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

April 1944 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

April 1944 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

April 1944 By JOHN MOODY

LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00

-

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

November 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

December 1942 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

May 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleBrief Biographies of Buildings

June 1943 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleTOPLIFF HALL

March 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1950 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00