MY PROFOUND DISAGREEMENT with both letter and spirit of Dr. Cowley's article in the May issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE leads me to accept with some pleasure the editor's invitation to comment upon certain of its implications. Dr. Cowley raises some old ghosts and evokes some false enmities. There is enough enmity in the world today without inviting civil war between the colleges and the universities of America. If the enmities were real and deep-seated, we should have the issue out. I have called them false, and shall try to say why I think they are false.

But let us first lay the ghost. It rises in the form of Dr. Cowley's statement that "the universities belittle liberal arts colleges." The evidence, according to Dr. Cowley, is to be found in an article by Professor T. J. Wertenbaker of Princeton University. The article appeared in 1934 under the title, "Our Intellectual Graveyards," and has apparently troubled Dr. Cowley greatly since that time. It need not have done so.

Let Dr. Cowley reread the article. Professor Wertenbaker was not assaulting the liberal colleges as such. His career has been devoted to the championship of the American idea of liberal arts curricula. Nor did he describe as intellectual graveyards the non-university colleges which Dr. Cowley enumerates: Amherst, Bowdoin, Dartmouth, Hamilton, Lafayette, Swarthmore, Wesleyan, and Williams. To imply that he did so is not only an error; it is a twisting of facts to support Dr. Cowley's untenable thesis that the universities belittle liberal arts colleges.

The intellectual graveyards Professor Wertenbaker had in mind were those little colleges (often narrowly denominational and provincial) which in the early years of our educational development proliferated like weeds all over the American scene. In the nine- teenth century there was a place for them, as there was for college fraternities, and they filled that place. That is, they filled it as well as they could, with low standards of admission, inadequate physical plants, hopelessly antiquated libraries, and faculties that were overworked and underpaid. They were intellectual graveyards for any Mr. Chips who drifted into them. They represented a stage in the growth of American education beyond which we have passed, and they survived into the present century at least partly by inertia, as did college fraternities. During the depression many of them closed. The present war will close others, and if they are as bad as Professor Wertenbaker says they are, it will be no great loss to liberal education. For they were colleges in little but name; the brand of education they offered was inferior; they were liberal in no definition of the term that I know of.

It is not a question of inferior education versus no education at all. These little places are very far from the last strong-hold of liberal arts curricula. Those students who might have attended the tiny colleges can always attend strong, independent, liberal arts colleges like Dartmouth, or their own state universities. Or they can take the (to Dr. Cowley) tremendous risk of going to Chicago, Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, or Yale, where something awful called "specialization" will perhaps happen to them, though at the undergraduate level, I doubt it.

I think that Dr. Cowley misinterprets the Wertenbaker article. Although I hold no particular brief for the article itself, it is not an assault on liberal education. Nor is it an attack on the strong, independent liberal arts colleges. It is a moderately feasible argument for saving the best of the little liberal arts colleges by enabling them to cooperate with the universities in their vicinity. The goal is emphatically not the subversion of liberal education, but the attempt to guarantee its survival by assisting those little colleges to do better teaching, to attract better students, and to maintain higher standards than would otherwise be possible.

SPECIALIZED VS. LIBERAL

It would be possible to presume on the editor's kindness by taking issue with Dr. Cowley on a number of other implications of his article. I shall stop at one, though this one is important. He assures us that "the universities—even Harvard and Yale—give the major portion of their energies to specialized education rather than to liberal education." It would be useless to deny this point in toto, especially when we consider that many state universities have yielded to strong pressure from practical politicians to teach the socalled "practical" specialized subjects. It is probably true of Harvard, with its great graduate schools of divinity, law, medicine, and business administration. But it is less true of Yale and certainly untrue of Princeton. Let us not forget that the core of education at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton—as at Dartmouth, despite its associated schools—and at many of the best state universities (viz. North Carolina), is still the liberal undergraduate curriculum. If Dr. Cowley insists in putting it on a quantitative basis, these great universities expend far more time and effort (in actual man-hours devoted to liberal education) than many of the tiny places Dr. Cowley is apparently so anxious to perpetuate. Moreover they do a better job. The quality of liberal arts education at Princeton, for example, is as good as that of Dartmouth, as I can personally testify. It would only irk Dr. Cowley if I said that it is a shade better. Nor, to pursue the point one step further, do I believe for a minute that there is any major disagreement between these universities and the liberal arts colleges as to what constitutes liberal education.

I should like to hope that Dr. Cowley intended his article as a healthy stimulus to healthy discussion for the greater glory of the liberal arts cause in this country. If this be so, more power to him. But there are other and better ways of educing healthy argument on educational aims than by misreading nineyear-old articles, and digging chasms between good liberal arts colleges and good universities where no chasms existed before.

Asst. Professor of English,Princeton University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

June 1943 By Dick Paul '41 -

Article

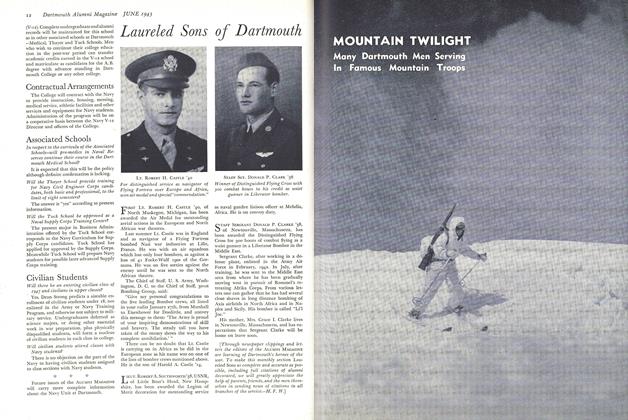

ArticleMOUNTAIN TWILIGHT

June 1943 By LT. CHARLES B. MCLANE,'41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FREDERICK K. CASTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

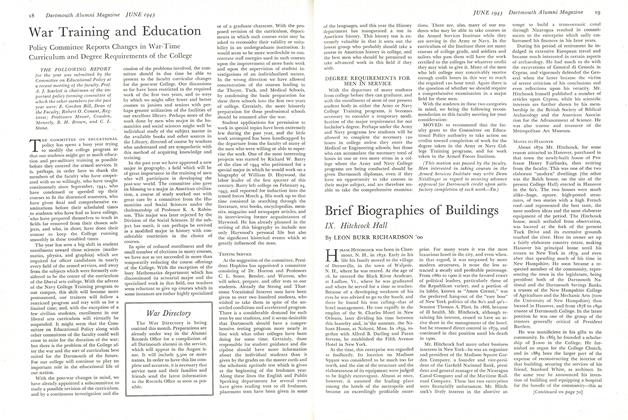

ArticleWar Training and Education

June 1943 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meeting

June 1943

Carlos Baker '32

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

December 1920 -

Article

ArticleFund Committee Active

November 1928 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

January 1936 -

Article

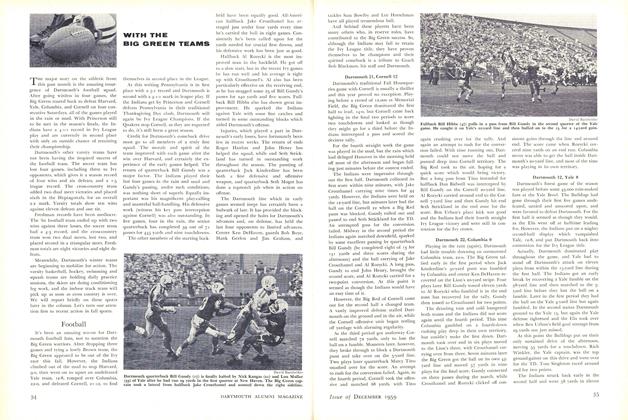

ArticleDartmouth 22, Columbia 0

December 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleDeborah Nichols and John Watanabe, Act I: The Big Year

SEPTEMBER 1997 By HEATHER MCCUTCHEN '87 -

Article

ArticleSentiment and Reason

April 1940 By The Editor