Letters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

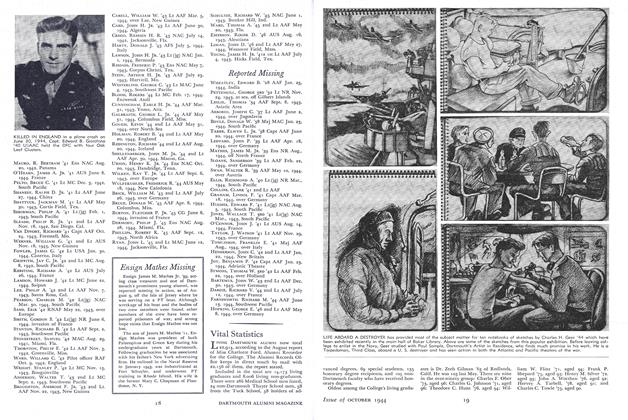

Permission has been received from the Chicago Daily News to reprint a letterfrom MAJOR JAMES A. DONOVAN JR.'39, USMCR, which describes the Battle ofSaipan. This letter appeared on July 18,1944- Major Donovan was also in theTinian engagement soon after Saipan.

We landed on red beach 1 under heavy fire at 1030 (10:30 a.m.) of D-Day, and lost quite a few officers and men," said the major. "The Japes—that's what we call 'emscored several direct hits on the amphibious truck I was riding in.

We were able to get ashore although one man's head was blown off, and eight other marines were wounded. We saw little action the rest of the day, although Our casualties were heavy.

We had it hot for a while when the Japes broke through to our command post and pinned us down in foxholes with kneemortars and machine gun fire.

It was not until the next night, though, that our turn came and the Japes hit us with a big counter-attack. They sent 27 tanks and a lot of infantry against us.

With the Jape troops on the outside and others on foot, behind, the tanks rode right over our foxholes, but our boys kept their heads, stayed low, and nobody was crushed.

We really stopped them. One of our men stuck a log in the tread of a tank and stopped it dead. When its Jape commander threw open the tank hatch, the boys tossed in a grenade. Our battalion anti-tank company then got into action and knocked out every enemy tank. We ourselves got lead into half of them with grenades and bazookas.

The Japes didn't gain a single bit of ground and beat a retreat after a threehour battle lasting from 3:30 to 6:30 a.m.

At 7:30 a.m. we shoved off. Our boys had been up all night fighting but took off without a whimper and went right up to Hill 790, our objective, like winged apes. It gave me a tight feeling in my throat to see the way they pitched in, tired as they were.

As we were advancing we noticed a Jape tank maneuvering on the hilltop. Our shore fire-control officer radioed to a destroyer. It sent about 20 salvos into the tank. When we arrived the tank was just a mess of scrap iron—but the telephone was still intact and ringing.

Without bothering to say, "So sorry"—we had no time for customary courtesies at that point—we established a line forming a left curve from the beach inland about 2,000 yards. One of our company commanders ran into a Japes strongpoint in the rocks a few minutes later. Japes were shooting out from the rocks and looking down our throats.

In the next 15 minutes that company command changed hands three times. Its original commander was killed. The executive officer took over, and he was shot. The next officer in line took over, and he was shot. After that we began pushing northward on short hops, and patrolling.

"From time to time, we were shelled and gunned with everything the Japes had, and once one Of our own fighter planes dropped a belly tank on us, but no one was hurt. We had been fighting along the western slopes of Mt. Tapotchau. It's pretty rugged country, as you can see—full of caves like that one we're flushing out over there with flamethrowers and TNT.

On July 2 we began the big push, tied in with the Red Battalion's assault on Garapan.

On July 3 we continued our push and on the morning of the Fourth of July, we drove down from the ridge to the beach north of Garapan. That was our final objective and our mission was accomplished.

You ask if we used tanks. We did where there were roads on ridges, to support the infantry. We did not use tanks according to Hoyle, but we got results. For the most part, though, it has been plain, hard footslogging.

LT. MALCOLM McLANE '46, USAAF,son of John R. McLane 'O7, of Manchester, N. H., has written a most interesting letter from England in which he describes D-Day from the point of view of aflyer.

It's three o'clock, Tuesday morning, June 6, 1944- Someone is shaking you in your blanket roll, but you're too sleepy to get up for you didn't get to bed until midnight and it was after one before the talking quieted down and you got to sleep. Then the bright light goes on in your face, and you remember what you were told in that three-hour long, secret briefing last night, "Today is D-Day!"

You tumble out as best you can, put on extra socks and heavy shoes from force of habit, for some day you may have to walk back. There's some hot coffee and an egg in the mess tent, then you pile into jeeps and trucks and hurry to the line, where the ground crews have already been warming up the planes. There's your Mae West to put on, your helmet and goggles and chute to put in the plane, before you pack into the squadron briefing tent and get courses and instructions regarding your mission. There's no comment on the weather, as there usually is, for it's obviously terrible. Ordinarily the mission would be scratched, but there's no cancelling this one. Fifteen minutes before start-engine time you're in your plane, checking everything and getting buckled in. It's still dark, for the sun isn't due to rise for over an hour and there won't be much twilight with this solid overcast and misty rain with its low ceiling and visibility. Belly tanks cause some trouble as you taxi out, but there's no waiting for stragglers and those that can make it are off the ground and circling over the field, trying to get into formation. It's no easy thing and many wander home alone.

Once you've set course, you must climb up through the overcast on instruments.. The formation breaks up even more, and when you break out on top, headed into a full moon and a clear sky, you find yourself alone on your element leader's wing. The rest have popped up through the blanket of clouds on their own, and are doing their best to find the patrol area separately. Navigation is a matter of compass headings and timing, for there are no landmarks here over this ocean of white. To the east the sky gets lighter all the time. After an hour occasional breaks appear below and the two of you spiral down to reconnoitre. It's France alright, but where? A radio call and a fix and soon you're given a heading to the target. Below the clouds it's murky again, but the light behind you is getting pinker and the fleecy clouds at the bottom of the overcast are a lovely soft red. Below ships begin to appear, their guns flashing in the darkness, while the rising sun brings out their forms gradually and makes the water a deep red. The air is still misty and the visibility poor, but this only adds to the sun's reddish glare.. For another hour you patrol back and forth over the beachhead-to-be as the big guns pound away. And then when you're about to leave, for your gas is getting low, a little fleet of boats leaves*, the great fleet off shore, passes the outermost ring of destroyers and heads for the beaches. As you head back across the channel to England, the scattered small wakes of the landing craft near the shore and in another few minutes the Invasion will have begun.

More planes will relieve you, and many more ships will follow those first boats, but that hour before- H-Hour will be a neverforgotten memory of this war, whose other details I will willingly forget. My part was nil, for there was no opposition from the air, but our mission was carried out and the beachhead won.

CAPTAIN CHARLES W. MILLS JR.'34, USA, MC, writes a long and interesting letter from Italy in which he paysdeserved tribute to the footslogging infantry.

A few days ago the June issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE arrived, and today one of the class newsletters. It is always such a treat to receive Dartmouth publications.

The division is enjoying a few days well deserved rest along the shores of Italy in the vicinity of one of the resort towns. It is quite a beautiful locatipn, and all of us are. enjoying the swims in the Mediterranean.

After serving as a battalion surgeon for eight months, I am now in the position of assistant regimental surgeon. It is definitely a rear echelon job, the duties of which are mainly administrative in nature.

My orders assigning me to the - Division reached me late last November. It was a great delight to be transferred from the hospital, but the prospect of joining an infantry division was none too pleasant, particularly since I had never had one day of field service during my two years in the Army.

The division surgeon assigned me to the - lnfantry Regiment, and then in turn I was assigned to one of the battalions. The latter I joined in a muddy morass at the base of Montequila (the spelling may not be correct).

A few days later the battalion marched over the mountain during a terrific storm to get into position on the mountain above Pantano. It was a march of 16 hours through mud and "torrents, and the first exercise for me in many and many a month, but surprisingly the legs took me there.

Pantano turned out to be an extremely tough assignment, and I fear that my battalion did not receive the best in medical evacuation, as the assistant surgeon with the forward aid station was extremely green. Fortunately, the enlisted men knew the score, increased my total of one litter squad to ten, and set up a series of relay posts on the mountain. The men were brought down, but it was grueling work for the litter bearers.

During the rest period after Pantano I was assigned to another battalion as the surgeon, and remained there for several months.

It was in this latter unit that I met some of the finest men it has ever been my privilege to meet. The battalion commander has no peer, the staff and company officers were excellent, and for the most part we had an extremely high caliber of doughfoot.

Early in January we attacked and captured the village of San Vittoire, then moved across the valley to occupy Mt. Trocchio. Later we sat on the flats in front of Cassino for a few days, then swung north through the village of Caira, ascended and took Mt. Castellone.

Jerry was on the run and we pushed him back to within a mile of Highway 6, and would have cut off Cassino then, but we had been well whittled down, and there was no one to push through us, or to hold all the territory we had taken. When the troops had to stop and take up defensive positions, our casualties mounted. Mortars, artillery, and small arms resulted in us finally coming off the mountain with 12 to 18 riflemen per company.

No one will ever be able to talk to me about the decadent youth of America. Those men were on those mountains for days and days being constantly subjected to heavy fire, living in their wet clothes, enduring freezing, wet and snowy weather, and eating C Rations.

A few weeks for reorganization and training and then off to the Anzio beachhead.

The highlight of that was the breakout of it. We were teamed up with the Armoured Division. There was much preliminary briefing and maneuvering to get together before D-Day, but it paid big dividends, and the attack went off like clockwork. It was beautiful. Tanks and infantry never worked better together.

Within a week we were fighting as straight infantry again, and found ourselves in a terrific spot before Lanuvio. We were evacuating a goodly share of men from five battalions, plus attached artillery, tank and tank destroyer units. Every one of my men was a hero. Seven litter bearers were killed, so you can see that it was rough. Jerry took a lot, too—after it was all over 350 dead ones were counted in front of our battalion sector alone.

We were then attached to the —Armoured again, and with them were, the first to enter Rome. We chased Jerry many miles further north. After a couple of weeks' rest we again took up the fight, and pressed Tedeschi back to the Leaning Tower.

This is a very skimpy account of the bat- talion's activity. The men have done an excellent job. I do not think that one can really appreciate that unless he has been with them. A battalion surgeon does not really have a true picture of it, as he is 700 to 1000 yards behind the front lines, which is as different as day is from night. My hat goes off to the American combat infantryman, and I am humble in his presence. It has been a good eight months, and to have been a member of that bat- talion has been a great privilege.

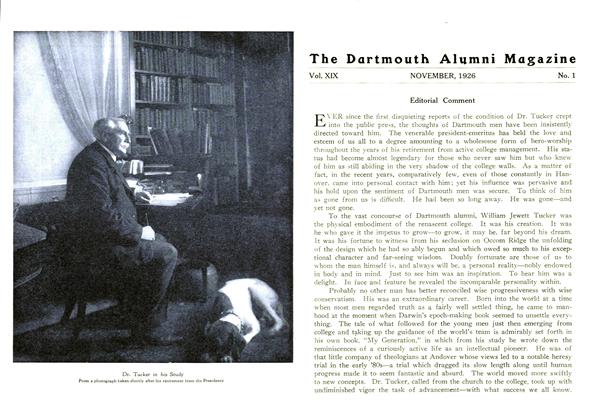

HALFWAY THROUGH THE BATTLE OF SAIPAN, Major James A. Donovan Jr. '39, USMC, (second from right) takes time out with some of his fellow Marines for coffee. A battalion commander, he describes some his South Pacific battle experiences in this section.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleAnother Sgt. York

October 1944 By Ivan H. Peterman -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CASUALTIES

October 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONAI.D L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1944 By RICHARD B. KERSHAW, WILLIAM C. WHIPPLE JR. -

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

October 1944 By Al Goldstein '47

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

NOVEMBER, 1926 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCADET BOLTE REPORTS VARIED EXPERIENCES

February 1942 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

June 1945 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPostscript

JUNE • 1986 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

April 1944 By H. F. W.