VARIETIES OF COLLEGES

A THOUGHTFUL writer on educational topics, Myron M. Stearns, has lately published, through John Day, New York, a little book entitled "What Kind of College Is Best?" It appears to be not so much an attempt to be specific as to the merits of particular colleges, but rather to generalize as to the types of college available for choice. In the course of a pilgrimage about the country, the author states that he found a surprisingly great number of choices made by chance, or sheer caprice; and he appears to feel that benefit would result if more intelligence were exerted in advance on determining why one should choose this or that college, with a view to the special needs of the chooser and the probability that the college chosen will serve those needs. Even so, it is to be suspected that, apart from exceptional considerations as to technical or nontechnical training, the present excellence of most recognized colleges is so great as to make it possible for the boy who really wishes an education to get it almost anywhere, with more doubt as to the likelihood of the college environment to foster that desire, or keep it alive, in one case or another.

Mr. Stearns specifies five general categories as making up the 600-odd colleges now listed in the archives of the United States Bureau of Education. These are (1) the famous technical schools, of which the Massachusetts Institute of Technology may serve as an example; (2) the "grand old colleges" of the first magnitude, such as Harvard and Yale; (3) the smaller and medium-sized colleges scattered over the country in such bewildering profusion, whereof New England has certainly her full share; (4) the cooperative or part-time colleges, such as Antioch; and (5) the state universities, which carry on the idea of the public school supported by taxation, some of which are of enormous size. The argument is that the intending applicant should first satisfy himself as to the variety of college he wantsand then make conscious effort to discover which particular one in the chosen class seems best to fulfil the requirements.

How far it is possible to overcome the natural tendency of boys, and their parents as well, to make the choice a matter of mere fancy, sometimes without fully knowing why, is not easy to estimate. Those who have had most to do with winnowing applicants for Dartmouth since the Selective Process was adopted have no doubt done their best to discover why those who came before them chose Dartmouth rather than some other; and the reasons advanced are not always very definite. Often an applicant will say what first comes into his head, not having put any thought on it before. He has had friends at Hanover, or he likes the idea of a college in the country, or he has an eye on the Tuck School as about what he wants, or he is fascinated by winter sports, or feels that among the colleges of less than the greatest size Dartmouth has a standing that attracts him. One omits the number, naturally large, who prefer Dartmouth because of family connections with it through one or more past generations. It is probably the same with every other college in the land and always will be. To expect a careful analysis and estimate of competing claims is probably to expect too much. This cloth or that will make a suit of clothing capable of keeping the wearer warm and making him presentable. Why do we finally chose one rather than another—a pencil-stripe, a herring-bone, a brown, blue, or gray? The fact is we do not always know just why we choose, but something impells us to a preference whether it can be identified or not. Individual colleges have naturally their special personalities and special reputations, but commonly enough one chooses without more than a vague idea of what they are. Would the results be greatly better if one did know?

Choosing a college for the boy is more or less a lottery—in which respect it differs little from the choice of a mate for life, although in the case of the college it usually makes less difference in the end. Almost any college today can give the boy who wants it about the same amount of education that another would give him, and the choice narrows down to a matter of the college personality. For colleges have that quality, as surely as do individual beings; and on what the applicant knows or assumes thereof is likely to depend his selection. It may not be mere caprice after all.

THE NEW COMBINED MAJOR

Two YEARS ago President Hopkins, in a letter to the Daily Maroon commenting upon the reorganization of the University of Chicago, made the following observation:

"The plan is courageous in that it divorces itself from the autocracy of the departmentalized curriculum, wherein the assumption exists that a man can become educated by the acquisition of a few fragmentary bits of knowledge, whether or not he knows anything about the articulation of these with each other or what their importance is in the body of knowledge as a whole. A liberal education ought to cultivate some sense of proportionate values in learning, as elsewhere. Too frequently, no sense of this is given to the college curricula turned over to departmental jurisdictions."

Dartmouth, like most other colleges, has found two prominent obstacles in the way of this "sense of proportionate values." One of these was the "free elective" system, the practical effect of which was such a random choice of studies that students would only infrequently revolve their work around some central nucleus in such a way as to get a coordinated impression of the different individual parts. This freedom of selection was severely restricted a few years ago, when it became obligatory to choose fields of concentration for junior and senior work. Since that time, the second obstacle has become conspicuous: a too rigid departmentalization of fields which display unusually close interrelationships. In other words, the fields of concentration have been so narrow, so much work has been required in a given specialty, that perspective has suffered. The problem has been to exhibit the relationships among closely kindred fields without at the same time obscuring useful distinctions of content and method. Some progress toward the solution of this problem has been made by means of the "combined major," a recent example of which is the combined major between Economics and Political Science.

The new major does not eliminate the Political Science and Economics majors as they have existed, but it gives to those students who choose it an opportunity to select their major course from the lists of two departments, subject, of course, to the approval of advisors in each who will take care that the selection creates a coherent whole. Seventeen men in the present junior class have elected to try the new major.

In selecting between the two departments the student has a wide latitude of choice. He must take three lower division courses: the introductory course in Economics, the introductory course in Political Science, and the introductory course in either Philosophy, Sociology, or American History. Twenty-four upper division units may be divided equally between the two departments, or in a ratio as unequal as eighteen and six for those students who prefer to emphasize one field over the other. Through his senior year he will enroll in a correlating course in which an effort will be made at synthesis.

Something may be hoped from the plan for its effect upon teaching, cracking as it does the departmental lines, it reduces the likelihood of unduly heavy emphasis upon vocational or professional training. It affords a means by which the student may grasp the "proportionate values" of things which are so closely related in fact that they need to be seen together. It avoids two dangers inherent in mere merging of different departments of social study into one department: first, the danger of failing to observe important distinctions; second, the danger of giving too much emphasis to the point of view of a particular field. Finally, it affords the hope of expanding a two-dimensional into a multi-dimensional social science.

VOLUME TWENTY-FIVE

WITH A NEW style of dress the MAGAZINE pur- poses to provide alumni with a better balanced publication, presented in the improved format, for their enjoyment and edification in post college years. Aided and abetted by those able and tireless directors, the class and club secretaries, these pages will chronicle during the year the many and varied activities of thousands of Dartmouth men. With the promise of articles from an array of talented con- tributors the editors feel confident of a high quality feature section. Professor Bowen's new column on books—"Hanover Browsing"—fills a long felt need.

This is Resubscription Month. Every effort will be made to make the MAGAZINE worthy of the group it serves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCHANGE IS OPPORTUNITY

October 1932 By Ernest Martin Hhopkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1922

October 1932 By Francis H. Horan -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1932 By Prof.Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1932 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

October 1932 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1905

October 1932 By Arthur E. Mcclary

Lettter from the Editor

-

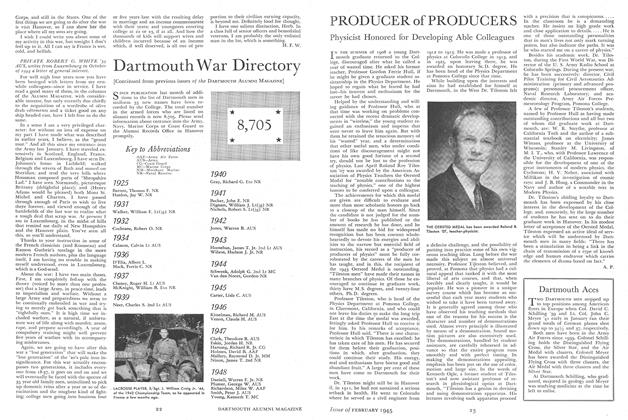

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorMemoirs of a Great Editor

October 1937 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDateline Hanover

MARCH • 1986 By Douglas Freewood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou could say a woman started it all.

MARCH 1997 By Karen Endicott