For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

STUDENT WRITINGS

IN view of the propensity of elders to disparage the conduct and productions of youth, it may be interesting to consider for a moment a thought suggested in a recent issue of the Saturday Review of Literature concerning student publications, such as undergraduate periodicals. Such naturally reflect the fashion of the time, and as a wholly natural consequence are far more elaborate in extent and character now than they were some 40 years ago. The more significant thing, however, is their change in tone.

In Mr. Canby's editorial if it was his it was suggested that critics of the modern youth might be assisted to a saner judgment of the modern product if they would only turn back to the publications of the '90's and contrast the rather stilted and turgid literature of undergraduates in that day with the more spontaneous and direct productions of the present. One who remembers the short-lived Dartmouth Literary Monthly of the older days, with its restricted list of contributors who were bent chiefly on writing like Matthew Arnold and producing owl-like critiques of literature, may find something distinctly refreshing in the less portentous but far more genuine writings of the current age.

Each era has necessarily the defects of its qualities, and the present, with its lack of reticence and straining after realistic frankness, doubtless has defects enough; but it is improbable that the candid observer can bring himself to sigh for the good old days when the leaning was all toward a Miss Nancyish regard for moral and literary prunes and prisms. If at times he thinks he might, it will help to get down a file of the older magazines turned out by the aspiring and inky students of 40 years ago and re-read what appears therein. Generalizations are dangerous, but it is a defensible belief that the world, for all its shortcomings, is improving on the whole, and that even college writing reveals the tendency toward a more genuine service of the realm of letters.

TAKING IT EASILY

AT the special urgence of the trustees of the College, the President will this winter forego many of his usual appearances before alumni gatherings because it is felt that it is not doing right by the College to permit the President to expend himself so extensively in this form of activity, which demands prolonged absences from Hanover and entails a great physical strain owing to long railroad journeys. Dean Laycock, with whom the President has always alternated these alumni engagements since the number of associations became too great for the two to travel together, will represent the College, as will Dean Bill at some few points. With few exceptions, therefore, President Hopkins will be absent from alumni dinners in the East and Middle West; and whether or not he can be spared for the long trip to the Pacific coast is as yet indeterminate.

It is probable that the President regrets this suspension of his usual program as keenly as does any one else, for beyond doubt his contact with multitudes of enthusiastic alumni is a constant inspiration, as it would be to any man. The fact is, however, that to reconcile these extensive journeys with the pressing demands of the job at Hanover is never easy; and while Mr. Hopkins is now in the very prime of life, it is plainly for the best interests of us all, as well as of himself, to avoid overstraining the human mechanism. No alumnus will question for a moment the statement that the President is the most important of all our College assets, or overlook the fact that prudence counsels maintaining this asset at its maximum of efficiency for the future years. Therefore, greatly as thousands of alumni will regret the omission of the customary winter tour, it is bound to be approved; and the more so, happily, because such competent exponents of administration policy as the Dean and Director of Admissions will step in to serve as locum tenens.

Or, should we say, locum tenentes? One's Latinity grows rusty with the years! But one recalls Congressman Tim Campbell's lucid explanation that "Locum tenens is Latin for pro tem."

ANNUAL ALUMNI CARNIVAL

THERE will be general rejoicing among those fortunate enough to live within striking distance of Hanover to learn that the Outing Club has added to its multifarious duties the responsibility of arranging and carrying through the annual Alumni Carnival. For some years alumni have been filling the Inn on the week-end nearest Washington's Birthday. Three years ago these informal sojourns were given a name and a purpose: that of Alumni Carnival, which has since come to be regarded by New England and New York Dartmouth men as an annual event. With the excellent program arranged by the D. O. C. in cooperation with the Inn and the athletic council notice seems to be served that this mid-winter event may assume a role of real significance in the life of the College.

For the Outing Club's execution of well laid plans has never been improved upon by any college organiza- tion. Even to the detail of providing snow and ice at desirable times the Club has a record of 100% to date, and it has our very best wishes for the future. Although the latter part of February is not always as kind in the way of winter sports weather the season is usually a good one. There will be more assurance, at least, in the minds of all those interested in the week-end events of February 20-21-22 now that the Outing Club has taken charge.

Home-comings are the order of the day at manycolleges. Except for occasional events of considerable importance Dartmouth reunions have been confined to the Commencement season in June. The annual Alumni Carnival in mid-winter promises much in the way of recreation and renewal of Dartmouth associations. One item of the Committee's plans is to arrange for the attendance of such alumni as may be interested at lectures and class work during their visit.

The prospect of slipping back into Hanover life with varied diversions to be taken as needed is a most pleasant one.

THE FUND GOES ON

IN a later issue, more definite discussion will be set forth as to the part which the Alumni Fund must play in these critical years and of the extent to which conditions can be met in other ways, as by reductions in college expenditure and overhead costs, without throwing away all we have gained in the years during which Dartmouth was increasing to its present size and prestige. For the moment one must be content with the statement that such curtailments must necessarily be limited. Every economy is being effected where there will be no resulting loss in teaching accomplishment. Largely through the annual Alumni Fund campaigns the College has grown to its present stature. In no way can its strong position be maintained except through the continued support it may anticipate from this reliable source.

The last previous report was of the 17th Alumni Fund collection, which was instituted in a very modest way in 1906 and which bears the name of our first great modern president, Dr. Tucker. The quota now set but as yet not realized is $135,000. No one in 1906 would have dreamed of attaining such a figure; but it will be done eventually, even though the intervention of hard times postpones the repetition of an achievement which has marked the setting of each preceding quota. As time has gone on and as alumni have educated themselves to regard this contribution as a fixed item in the family budget, it has been possible greatly to reduce the cost of "selling" the idea, and also to reduce the amount of time devoted to each campaign. We all know about the Fund now; we all have seen its beneficial effect on the steady growth of the College; and we have most of us learned to be merciful to our class agents in the matter of prompt responses.

It has been described as an acid test of loyalty, but it has always been nobly met. The harder the conditions, the more the glory in meeting it. This we mention at this time merely to remind readers of the fact that the Fund goes on, and that in present circumstances it is, if anything, more important than ever before in the past 18 years. The College has cut expenses all it can and still be the Dartmouth we are all so proud of. A deficit for the year is unavoidable. The Fund must bridge this to the extent of its capacities.

PEDAGOGY

EVERY year there arises in circles more or less in touch with the curricula of colleges and universities an occasional voice of adverse criticism concerning the ideas which teachers present to their classes. One teacher is condemned as an "atheist" another as a "Bolshevik" another as an "anarchist" (and whether or not such types merit condemnation is not discussed here), whereas the truth of the matter is the teacher in question is nothing of the sort, but is merely attempting to present one point of view in order to stimulate thought in his classes. For example, if a professor comes to class and says (in the words of Lenin) "Religion is opium. . . . Now write me your reaction" then as news of the exercise is bandied from mouth to mouth it takes on more and more emphasis until the author of the exercise is labeled a "Red," or an outcast of similar description, whereas the truth is that teacher in question was using a certain common pedagogical method in order to get mental activity in the group he was facing.

Thinking among most people is a property possessed of similarities, and in some cases it is only by the expression of some deeply partisan point of view that a reaction from a class is possible. If education helps men to think, and it is a belief among educators that some such goal is desirable, the "shock" method is certainly ethical. The only trouble with the system is that occasionally class room utterances get into print, and that which the teacher enuciates is taken to be his real point of view, whereas it often happens that his own private point of view is the exact opposite. Teachers who have used shock methods during periods of the year when students' minds were more actively taken up with football or other outside activities, often worry a bit when they think of what the consequences might be if the classroom discussion should get into print, and they themselves accredited with certain points of view which they have adopted for the occasion in order to stimulate discussion.

There still remain a great number of people who ask their teachers to tell them the "truth" about great problems, religion, politics, literature, the teachers know the impossibility of arriving at definite truth in anything, but try to arrive at that which is of most value, a method of approaching that which seems the truth. And in dramatizing a certain point of view the teacher is quite likely to suffer if the discussion gets into print. No teacher attempts to destroy idealism, but idealism which is real can not be destroyed. No teacher attacks belief of any kind; belief which is well grounded can not be destroyed. To separate the false from the genuine method of approaching truth has always been a teaching aim. Thus PEDAGOGY, a poor word by the way, and the resultant discussion.

THE DOCTORS DISAGREE?

FROM recent outgivings by two leaders in American education, it might be assumed that the doctors are once again in disagreement and that a decision as to which party is right must be of the traditional difficulty. President Lowell of Harvard speaks comfortably of the present estate of college students as he finds them. President Butler of Columbia speaks most disparagingly of both school and college students as they appear to him. He criticizes them for bad manners, slovenly speech and dress, indifference to public questions of great pith and moment—although it should be added that this criticism does not relate to college youth alone, but embraces all youth educated according to current ideals in our American school system. President Lowell, on the other hand, finds the Harvard student of the present day "more mature than a generation ago, not only in scholarship but in outside interests and a sense of proportionate values, which is the flower of maturity."

Now it is quite possible that the seeming conflict is more apparent than real, for each of these educators is speaking of a different thing from that considered by the other. Mr. Lowell is considering college boys only, indeed Harvard boys only; and Mr. Butler, all youth. The latter's remarks are general, the former's particular. It need not follow that the colleges are failures merely because the whole system of public education appears to be falling short of producing a mature and appreciative public. Public standards of excellence are certainly not high, whether it be a matter of politics, society, art, or what you will. Mass production in education is pretty sure to turn out a rather cheap article, as it would do in any other line; and merely teaching boys and girls whatever they are fitted to receive, or are willing to receive, cannot make for us a nation of scholars. Mr. Lowell appears to feel that, with all the day's shortcomings, the colleges are turning out a more creditable product than they turned out a generation ago. Dr. Butler offers no statement on that particular point. He disparages the raw material on which colleges work. Mr. Lowell points out that, even so, the results are growing better.

Certainly the grade of undergraduate work has been raised in most of the colleges of the country above what it was even a decade ago, and it seems that during the same decade the influences which Dr. Butler deplores have been operating among the general public, such as deficiencies in the home training, as well as in elementary and secondary schools. If President Lowell is to be believed, the improvement in the colleges has more than offset the deficiencies of the educational system below.

At all events the colleges have sought to impose a standard of excellence, which an imperfectly educated public would never set for itself, and it is agreeable to find testimony from so trustworthy an observer that the effort is discernibly succeeding. It is wholly possible, whether or not it seems probable, that Dr. Butler would concur with his Cambridge colleague in this particular view of a general situation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOld Timers

February 1932 By Professor Emeritus Edwin J. Bartldlett -

Article

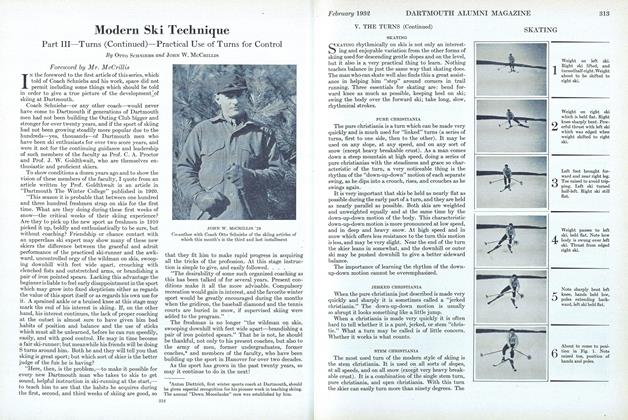

ArticleModern Ski Technique

February 1932 By Otto and John W. McCrilis -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

February 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

February 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

February 1932 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

February 1932 By Harold P. Hinman

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorREGARDING CLASS FUNDS

December, 1925 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MAY, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

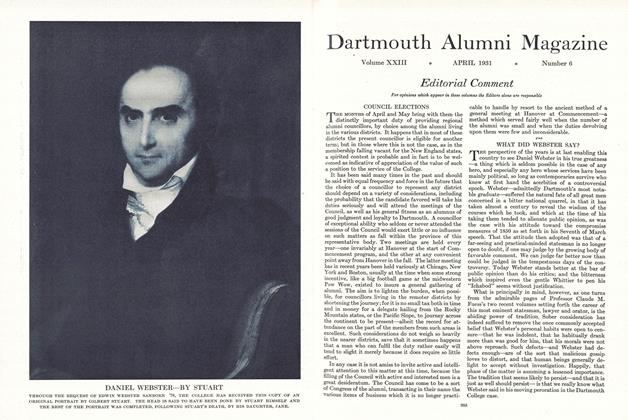

April 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

June 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

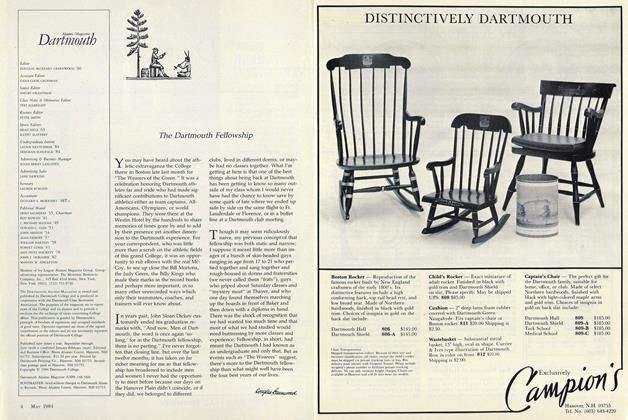

Lettter from the EditorThe Dartmouth Fellowship

MAY 1984 By Gouglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter From Paris

December 1948 By WILLIAM I. ZEITUNG '43