Distinction Gone ?

To THE EDITOR: How about passing my opinion of the band uniform along? I saw the pictures of the band in the December '43 issue. Our band, hitherto distinctive because of its plainness and simplicity—the soiled white flannels and green sweaters,—has now lowered itself to the level of the hundreds of other college bands who prance and perform in their pseudo-military uniforms. Have all the band either all civilian or entirely military, with either Navy or Marine uniforms!

c/o Postmaster,San Francisco, Calif.

Somewhere in New Guinea

To THE EDITOR This, is a hell of a place for a Dartmouth man. It's hot in winter and summer, which are reversed on this side of the equator just to make things more confusing; the hills would make good skiing, but there isn't even a cornflake. The only thing reminiscent of Hanover is the mud.

Yet if you stood at the airfield where the planes from Australia land or at the docks, in a booth marked "All Dartmouth men report here," you'd have relatively few lonely moments. There are Air Force men and Ground Force men and Navy men coming and going at an alarming rate; among them, you could piece together a most complete and well-rounded picture of this war in the southwest Pacific. These (all class secretaries please copy) are the incipient story-tellers:

Major "Kip" Chase '3O. Of all the alumni in this theater, he can probably tell the most complete story. The Major arrived in the southwest Pacific in April. 1942, when Australia had pessimistically decided to defend a line running through Brisbane, Australia, and let the Japs have the rest of the continent. The Japs were taking full advantage of that decision, having cleaned out Java two months before and having begun work on unprotected New Guinea, through Buna and the Kokoda Pass leading to Port Moresby. A short time after Chase arrived, another small man showed up—Gen. George Kenney, sent over to head the Fifth Air Force. The General assigned Chase to duty as his aide, and began the tremendous job of hitting the Jap from the air whenever he showed himself.

Major Chase stuck close to Gen. Kenney for a year, as the Fifth Air Force hammered the Jap at Kokoda and Buna and Lae and Salamaua and Wewak and Madang. The much-told story of Kenney's having two meals prepared for him daily, at his Australian Headquarters and at his forward operational base in New Guinea, 2000 miles away, holds true for Chase as well—he came to call the General's silver Fortress a second home. At times, Chase went over Jap territory in a heavy bomber on armed reconnaisance—one such trip is chronicled in a recent SaturdayEvening Post. While the rest of us can say we have caught glimpses of the war from time to time, Kip Chase can relate its pulse-rate from the very beginning.

There are others in the Fifth Air Force. In the famous "Jolly Roger" unit of Liberator bombers, Capt. Phil Conti '37 is the chief navigator, went on the mission with Maj. Chase about which you may have lead in that Saturday Evening Post. Ist Lt. John Twist '4l is an armament officer in that outlit. The "J°'ly Roger" organization, so-called because of the death's-head insignia painted on the tail of each of its B-24's, has accounted for some 300-odd Jap planes and a lot of shipping in its year of combat, has dropped thousand of tons of bombs on Lae and Salamaua and Wewak and Rabaul.

The troop carriers have their share of Dart mouth men, too—the troop carriers being the third air-arm o£ General Kenney's air force (second: fighters). The sturdy transport planes which have made swift movements of men and materiel possible over this mountainous jungle turned defeat into victory more than once. The writer was Communications Officer of one of the first troop carrier units in this theater (said unit having been twice cited by the War Department for its work in the Buna and Paupuan campaigns), tried almost every ground officer's job before ending up in Troop Carrier Headquarters as Public Relations Officer and sundry additional duties. Lt. Bob Schuette '42, is an Operations Officer; his outfit led the paratroop drop which inaugurated the drive on Lae. Capt. Fred Howard '3B flies a troop carrier C-47 besides holding an administrative job in his outfit: Ist Lt. Harry Thomas '32 is a ground officer in the same outfit, which spends its days shuttling soldiers and supplies to within uncomfortably few miles of Jap bases. Lt. Louis Deßus, ex-'36, a Pilot, fulfills the duties of Special Services Officer with his unit.

Lt. Ray Dau '4O, was here, but he's gone home. During his stay, he flew his Fortress over Rabaul many times, crash-landed once in the sea and once in the jungle with shot-up motors, escaped scratchless each time. Lt. (jg) Carl James '4O, is somewhere about with a Naval Amphibious outfit, disappears from time to time.

Anyway, without rancor—there's Bill Shelton '4O, a Naval full lieutenant, with the job of conducting liaison with the Army, also with a wife, a home, and a commuter's schedule. There's Lt. Stoney Jackson '36, also with an Australian bride, plus a child—he's moved, reports have it. Lt. Dave Lilly '39, is there, too, helping the Army's Finance Department figure out ways and means of keeping the national debt within reason. In another city are Lt. (jg) Vic Schneider '41, who communicates for the Navy, and Lt. Chet Ray '42, who does important work for the Army Signal Corps. It is rumored that he has won a citation for it.

Vic tells of running into two or three Dartmouth men in his office, deciding to have a meeting. They knew the editor of the local daily, so they inserted an ad for three days, giving the time and place of the meeting .... 16 showed up, 4 others called to express their regrets. Vic didn't get a list of the names, but he remembered the ranks stretching all the way from sergeant to full commander.

Needless to say, it's a pretty good thing to run into someone from Dartmouth, regardless of how many years apart you were in school. It's almost too easy, after a span of time in a place like this, to forget that there ever was or ever would be again, a place like Hanover—just saying the name of the college, in greeting, flashes refreshing pictures through the mind.

The war sometimes seems endless. Time flattens out, and months go by like weeks. As Richard Hilary, the RAF pilot who crashed in the Channel and lived to write about it, said, "War is a long period of great boredom, interspersed with moments of great excitement"—as this war moves successfully northward, the periods of excitement for those of us in established bases come less and less often. No longer can we sing "Hardships" to anyone, for we have made ourselves pretty comfortable. We've built permanent buildings with screens, we've made sure we'll have water for showers, we've arranged for food to be flown fresh from the mainland. We've built bars and stocked them, found orchestras and nurses to make parties, sat at outdoor movies and forgotten where we are.

We've learned that "creature comforts," made notorious by President Hopkins in that last pre-war year, could be pretty important when bullybeef and dehydrated potatoes were the menu for three meals a day, when showers and shaves came out of a helmet. We've appreciated our twice—or thriceyearly leaves to Australia as we never appreciated Boston on a Harvard weekend, though the difference was chiefly one of degree. We've learned, I think, that war doesn't change as many things as we expected, that it has its lighter sides as well as its dull and tragic ones. Like Dartmouth alumni everywhere, we've had a chance to examine what the College gave us, and we've found it good. As the class secretaries say—"Any time you're in New Guinea, be sure to look me up. I'm in the phone book."

New Guinea

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE MEN IN POLITICS

April 1944 By DAYTON D. McKEAN -

Article

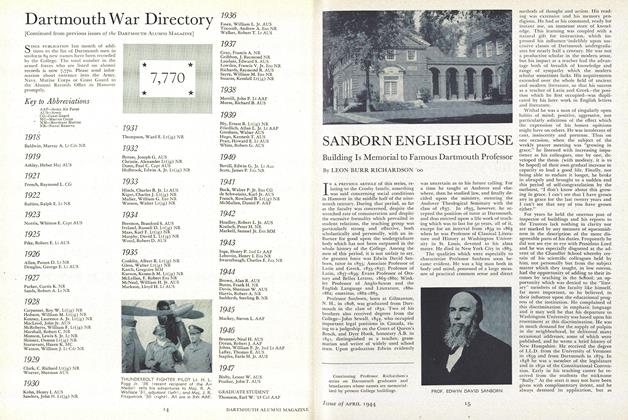

ArticleSANBORN ENGLISH HOUSE

April 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

April 1944 By ENSIGN JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

April 1944 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

April 1944 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCONTRIBUTORS' COLUMN

FEBRUARY, 1907 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA VIEW OF MENTAL HYGIENE IN COLLEGE WORK

June, 1922 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

March 1944 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

April 1956 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Nov/Dec 2001 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

July/August 2008