The Abuse of Science

To THE EDITOR:

I have just read Thomas C. Seawell's speech reprinted as "A Senior Talks about Dartmouth" in the February issue. While Mr. Seawell is to be commended for his serious concern with the state of the world today, I am deeply disturbed by the biased and pedagogical assumptions that he, as a senior extolling the virtues of the Liberal Arts curriculum of Dartmouth, has presented.

Had his remarks been limited only to his audience in Denver, the effect would have been limited. The fact that you have seen fit to print them as an "outstanding undergraduate statement" makes further comment necessary.

As one of the minority of graduates who majored in science, I have been increasingly concerned at the image of the scientist as an ogre in a white coat that apparently is held by a large percentage of the general public and, more importantly, is widespread among the youth of the U. S. The fact that Mr. Seawell can firmly state that he is "skeptical as to the real value of science" as a senior at Dartmouth College would indicate that his Liberal Arts curriculum has failed him badly somewhere.

The discoveries of science are not what have brought the world to its present condition but rather the use to which these discoveries are put, not by the scientists but by the world's political leaders, the military strategists, and the people themselves. We are not living in an age of science, but rather an age of technology.

Since leaving Hanover in 1940 I have met many scientists in many fields of investigation. Almost without exception these men have been highly educated men in the broadest sense of the word, with a profound sense of ethics and a serious concern for the abuse of science by society. Let Mr. Seawell remember that among our legislators in Congress there are only a handful who have come from a scientific background. Yet nearly all of these same legislators, who in the long run guide our national destiny, have a strong background in the law.

Can we feel that those trained in the law are without blame in our present dilemma? Do we feel that the world can be made better by other groups such as the clergy, the businessmen, the labor leaders or the philosophers? All of these groups are subject to their own biases and prejudices, and it is only with a true understanding of the value of the contributions of all of these groups to our society that we can hope for any great improvement in world conditions.

Let Mr. Seawell not forget that one of the great, truly international programs that has completely eliminated national boundaries and ideological prejudices at least temporarily has been the International Geophysical Year, a purely scientific undertaking of the highest caliber, completely untainted by political philosophy. Let him also muse on the fact that the most important steps that have been made in our international cooperation programs have been those of the scientists who have brought food to the hungry through improved agricultural methods, and elimination of disease through application of sound medical research.

Let us also never forget that scientists have been advocating peaceful uses of atomic energy since the early work of Einstein some 20 years ago. But even today our political leaders will make money available for military use of atomic energy but not for its peaceful development.

I hope that this article is not indicative of an attitude that Dartmouth must emphasize Liberal Arts for Liberal Arts' sake, rather than a truly "broad perspective of life" which Mr. Seawell praises but which he apparently has not yet obtained. The education of the whole man is what this country must continue to have. Narrow prejudices in any direction are not expected from Dartmouth.

Summit, N. J.

Don't Blame Science

To THE EDITOR:

(Re: "A Senior Talks About Dartmouth," February, 1959.)

It's not too surprising that Mr. Seawell's talk before a Dartmouth, alumni gathering was well received in view of the relatively high degree of isolation of Dartmouth alumni from the "mysteries" of the scientific community. Although he makes some good points, too trite by now to be particularly illuminating, Mr. Seawell displays the usual and unfortunate misconceptions of the liberal arts devotee about the nature and goals of scientific research, and about the true bearers of responsibility for the current age's chaotic misuse of scientific research.

The goals of scientific research have always been and still are those of applying reason, investigation, and insight to the problems of determining the nature and meaning of existence. The current terrors Mr. Seawell blames on science, including the annual highway slaughter and the existence of bombs and missiles are actually due primarily to the failings of our leaders in non-scientific fields, whose liberal arts educations, have not provided them with the foresight to anticipate the new problems of the world nor the courage to. meet them effectively. The share of blame due the scientists is not the huge one which their liberal arts critics ascribe to them, but rather the somewhat smaller fault of lack of faith in yielding to monetary and "patriotic" pressures to prostitute their talents in the insane practice of weapons development, usually euphemistically referred to as "defense."

Another aspect of the situation is the failure of the uneducated and liberal arts educated public to discriminate between scientists, a relatively small band, and the vast domains of engineers, inventors, and other opportunists reaping rich rewards from their useful but strictly non-scientific services, while basking in the prestige of science. (For an example, refer to the ad on the inside back cover of the February ALUMNI MAGAZINE.) Mr. Seawell shows himself prone to this misconception when he speaks of "a world in which each man's mind is dominated by science." (Perhaps a glance at the dictionary definition of science as "an organized body of systematic knowledge" would reassure him that such a state of affairs would not be so bad if it were so, as it unfortunately is far from being.)

Without the societal and fiscal pressures exerted by the public and its leaders, does Mr. Seawell really think that scientists would prefer working on Hell-bombs to the much more interesting fields of pure research? I say no. We do not live in a world of grade B movie "mad scientists," after all.

It is an unrealistic, dangerous, and futile luxury for us to allow ourselves to think that science is responsible for the ills of the present-day world. As always, these ills can still be laid to rest far more justly at the doorsteps of the politicians, religionists, and economists who have fallen short of their trusts.

New Haven, Conn.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

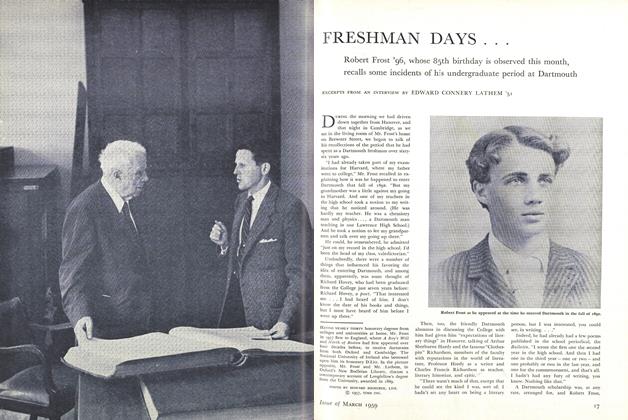

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

March 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"Spoiled Children" of Hanover: A Letter from Charles Doe, 1849

March 1959 By JOHN P. REID -

Feature

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

March 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1959 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1959 By ROBERT L. MAY, EDWARD J. HANLON, BRUCE W. EAKEN