V-12 History Course Helps Explain Why We Fight

THE NAVY, having entered the field of collegiate education, has issued its own "college catalogues" containing curricula and course descriptions. Therein we found our mandate for the basic course in history, commonly known as H 1-2. "The major purposes of this course," it states, "are to provide an understanding of (1) the complexity of our present-day civilization and of the inter-relationships of various aspects of society, such as agricultural, industrial, political; (2) the way in which the nation developed and the factors that contributed to its development; (3) the extent to which we have our roots in foreign soil; and (4) the more immediate background of the present war." A list of topics to be emphasized is given. We are directed to begin with the sources of colonial American population and the founding of American institutions and during the first term to trace the course of American development down to the Spanish American War and the emergence of the United States as a world power; in the second term we are expected to continue the account of the nation's internal history and then to stress such international developments as Bolshevism, Fascism, Nazi-ism, aggression and appeasement and the outbreak of war in 1939, especially with reference to their effect upon the United States. About two-thirds of the second term's work is devoted to American and international affairs since 1918.

The order has been a large and rather difficult one to fill satisfactorily since only two exercises per week are allotted to the course, a total of about 58 for the two terms. Trainees must often feel as though they are racing through history in a P.T. boat with the throttle wide open. For instructor and student alike the problem of what to emphasize in individual assignments is of constant and imperative importance. In our civilian survey courses, meeting three times a week, it has been customary to devote about 85 exercises to American history since 1783, with only sufficient references to overseas political, economic and social phenomena to explain our internal and diplomatic history. Even then we have often felt pressed for time.

The fact that a substantial majority of the V-12 men have had in secondary school a course in American history or perhaps one in Problems of American Democracy is of some help to them since there is a partial carry-over of knowledge—more general than exact, but not infrequently trainees hasten to the conclusion that H 1-2 is largely "old stuff" and can therefore be slighted in favor of other courses whose content impresses them as being of more immediate and practical value. This conclusion, together with the intellectual indigestion which our rapid survey tends to induce, unquestionably goes far to account for the rather long casualty lists we have had at the end of each term.

Faulkner's American Political and SocialHistory is used as the text for the American part of the course. This is supplemented by Stuart G. Brown's We Hold TheseTruths, a book of documents of American democracy, in which trainees are asked to read certain classic state papers and addresses such as the Virginia and Massachusetts Bills of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, the Federal Constitution and the inaugural addresses of Jefferson and Lincoln. International trends and events since 1918 are studied through the reading and discussion of Haines and Hoffman, The Origin and Background of the SecondWorld War.

The history of the past twenty-five years, although crowded with momentous happenings and tragic mis-steps and failures, holds the interests of the trainees best. Despite the fact that it concerns matters that have occurred within the span of their own lives, it is largely an unfamilar story to them. Most of them were in grade school when Hitler rose to power in 1933, and they were perhaps no more than high school freshmen when Czechoslovakia was partitioned. That unhappy land seems to many of them, as it did to Neville Chamberlain, "a far-away country' —and with much more justification. By the end of the second term the trainees have a reasonably good understanding of Japan's purposes in the Far East, of the circumstances which led to war in Europe in 1939 and of the reasons why they themselves are in uniform today.

To improve their knowledge of the elementary geography of American and world events of which they read, map studies' are required in conjunction with text assignments, and map quizzes, as well as quizzes upon readings, are given during both terms.

Nearly 800 men were enrolled in H-1 last July and about 650 continued with H-2 in the November term, the shrinkage being due in part to reasons other than scholastic failure. A new group of about 350 trainees entering in November began H-i at that time, bringing the total number of men to be instructed simultaneously in the course to approximately goo men. Our aim has been to teach trainees in groups of about 25 to a section, but during the first months of the V-12 program sections of necessity varied in size from 25 to 48. At present there are 39 sections, taught by 16 instructors, for slightly more than 600 men. Prof. W. R. Waterman shares with the writer the direction of H 1-2.

To staff so large a course, in addition to carrying along its survey and advanced courses, was from the outset beyond the capacity of the History Department since two of its members are in the armed services and others, before we knew that a basic history course would be required for V-12 trainees, had volunteered and prepared themselves to assist in Physics, Mathematics, and other courses where their services were urgently needed. Recruits were therefore drawn from the departments of English, Romance Languages, Political Science, Sociology, Economics and Public Speaking, several of whom had at an earlier time either taught American History or had done some graduate work in the field. That the transition from the familiar paths of their specialties has required of them, as it has for some of us historians, the burning of midnight oil and some last moment priming before going into class none would probably deny, but the job has been done with competence and good-will.

Aside from the use of a common syllabus in which assignments are specified and common hour and final examinations, no effort has been made to impose uniformity upon members of the teacning staff in the conduct of their classes. Each tackles assignments in his own way and naturally tends to color his presentation from the standpoint of his specialty and his literary interests, but the fairly similar results on the examinations have been reassuring evidence as to the desirability of our procedure. Furthermore, the favorable showing which our trainees made, in comparison with those in other V-12 institutions, on the Navy qualifying test a few months ago leads us to believe that in terms of content and instruction our course is fully abreast of what the Navy expects of us.

PROF. A. H. MENEELY, director of Naval History, who describes the basic V-1 2 course covering the backgrounds of the war.

DIRECTOR OF V-12 HISTORY

The MAGAZINE this month presents the third in a series of short articles describing the courses required of Navy V-12 trainees in the basic first-year program. Descriptions of English and Mathematics have preceded this article.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE GREEN FLIES HIGH

May 1944 By ARTHUR SAMPSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

May 1944 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, JOHN F. CONNERS -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

December 1951 -

Article

ArticleRevved-Up Students

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleKansas City Conference

December 1954 By CHARLES YANCEY '46 -

Article

ArticleWorkin on the Railroad

March 1976 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleMiscellany

January 1952 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Article

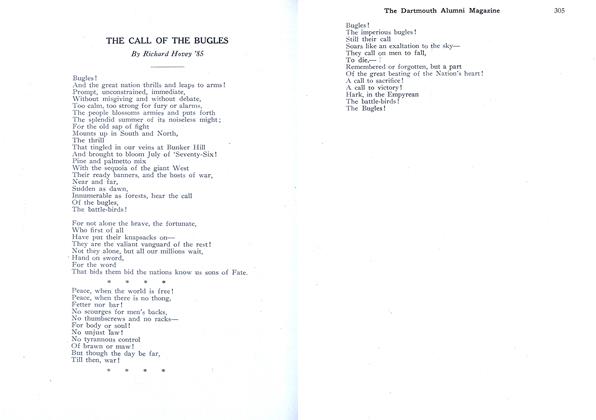

ArticleTHE CALL OF THE BUGLES

May 1917 By Richard Hovey '85