Third Oldest Existing Institution Nears 150th Anniversary

DARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL will reach its one hundred and fiftieth anniversary in 1947, having been founded in 1797 by Dr. Nathan Smith. Among American medical schools, it is therefore a venerable institution, as only two now in existence had been in operation before that date. Until 1812 it gave the degree of M.8., and for the next one hundred twelve years, the M.D. Since 1914 it has offered the first two years of the medical course.

At the time of its founding, there were no state licensing boards or other form of control over the practice of medicine or surgery. Consequently, there were many practitioners without sufficient training, to say nothing of a degree in medicine. The education of these men consisted of two, three or four years of association with a man already established in his profession. Their duties were often those of "hired men." They had the privilege of their preceptor's library, and during the long rides over rough country roads they received words of wisdom from the older man. They assisted at operative procedures and observed cases of illness under most primitive conditions. Few young men of this region at that time could afford the expense of living and studying at any of the city medical schools, and consequently medical care in the wilderness of northern Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine was in charge of men without formal education, and their efficiency depended entirely on the grade of knowledge of their preceptor and their own natural ability to apply the training they had obtained. Their pre-medical education was meager, and the men of that time are typified by what little is known of -the medical men of Hanover before 1800. A strange lot they were, but they do not belong to the story of Dartmouth Medical School. Interestingly enough, it is sufficient to say only that they had nothing to do with its founding.

The early history of the School is concerned entirely with one man, Dr. Nathan Smith. Much has been written about his life, but to give a basis for the story of the School, it must be repeated in part. Born in Rehoboth, Mass., September go, 176 a, he moved with his family shortly after to Chester, Vt., where he was brought up. Exactly what schooling he had is not clearly known but he was commissioned a captain in the Vermont Militia at eighteen, and probably served with troops in protecting against Indian attacks. We first hear of him teaching in Chester, Vt. There seems to be good evidence that he was twenty-one years old at that time.

Dr. Josiah Goodhue of Putney, Vt., was one of the leading surgeons in that section, and was called to Chester to amputate a leg. As was quite usual then, and was still true more than a hundred years later, the neighbors had gathered and were milling around the dooryard; and as was also not unusual, a volunteer was called upon to aid in holding the leg. Young Smith came forward and took the assignment. The usual duty of the "extra hand" was apt to be that of holding a lamp—a practice which years later, after the introduction of ether, meant catastrophe if the holder suddenly fainted and allowed the lamp to drop below the ether fumes. Thus, watching these lamp holders put one more burden on a possibly already harrassed surgeon. As a result of his experience. at that operation, Smith immediately applied to Dr. Goodhue to become his apprentice. The doctor showed his wisdom by inquiring as to the young man's education, and when learning of its sparsity, told him if he would prepare himself for entering Harvard College he would take him. So, as the story goes, Smith proceeded to study under the Reverend Mr. Whiting of Rockingham, Vt., and after a year presented himself to Dr. Goodhue and remained with him for three years. He then set up practice in Cornish, N. H., in 1787. at the age of twenty-five. Two years later he spent a year at Harvard and received a Bachelor of Medicine degree. His practice grew rapidly, and it would have seemed natural for him to have settled there permanently, but he recognized the necessity for some formal medical training in this section, and in 1796 made application to the Trus- tees of Dartmouth College ... to obtain approbation and encouragement by establishing a professorship of the Theory and Practice of Medicine " For various reasons the plan was deferred, but encouragement was given and future consideration promised. There is no evidence to suppose that he received more than mere encouragement or that he brought any influence to bear or enlisted anyone in his aid. Yet, in order to prepare himself for whatever might happen he set out for Edinburgh, the center of medicine of the world at that time, and after three months each in Glasgow, Edinburgh and London, he returned to this country in September 1797.

There is no record of Trustee action in 1797, but medical lectures were started in late November of that year in a house standing in front of the site of the present Old Medical Building. Dr. Smith was the whole faculty, giving lectures for about ten weeks in "Anatomy, Surgery, Midwifery, Chemistry, Materia Medica, and Theory and Practice of Physic." In August 1798 it was voted by the Trustees to appoint a Professor of Medicine and Dr. Nathan Smith was elected.

In a letter written in April 1811 to Dr. George Shattuck of Boston thus simply does the great man describe his work: "Respecting the origin of Medical School in this place. I gave the first course of medical lectures in 1797, beginning in November—was made. Professor in 1798. Dr. Lyman Spalding gave a course of chemical lectures in 1801 or 2,—he can inform you the exact date, and whether he gave one or two courses, I do not know. Dr. Ramsey gave a course on Anatomy in 1808. The State Legislature granted to me 600 dollars for chemical apparatus in 1803 and in 1809 granted 3450 dollars for a Medical Building, which is now begun and progressing and will be finished by the first of October. I obtained both grants by my petition alone." Actually Dr. Lyman Spalding lectured in 1798 and 1799. He became famous as the originator, in 1817, of the movement for a Pharmacopoeia of the United States, and was later Chairman of the Committee of Publication. The building above referred to is still in daily use for medical teaching.

In August, 1799, Room No. 6 in Dartmouth Hall was given over to the use of the medical lectures and later an adjoining room was added to this. On land given by Dr. Smith, the old Medical Building was completed in 1811, with funds, over and above those given by the State, furnished by Dr. Smith personally. This was repaid to him by the State in 1816. In 1873, $5,000 was secured from the State Legislature for much needed repairs. Four suites of rooms were incorporated at this time, for which some $200 rental a year was obtained from medical students. In 1871 the Medical School received from Edwin M. Stoughton of New York City the sum of $10,000 for the establishment of suitable rooms for the museum, for which since the first days of the School small sums had been spent for the purchase of specimens. This work was completed in 1873. In 1894 a new dissecting room was added to the south end of the building. In 1908, some $20,000 was raised through friends and alumni of the School and the Nathan Smith Laboratory was erected. This provided greatly needed laboratory space, particularly for the housing of animals. Before this time the College Library had handled all the medical books and from 1909 until 1914 the "strictly medical books" were shelved in this new laboratory; later in the Stoughton Museum. With the erection of Baker Library commodious facilities were furnished for a fully staffed, up-to-date medical library available to medical students, faculty, hospital staff, and others interested, and now contains some . 8,000 volumes and 15,000 periodicals. In 194 a, the Josiah Bartlett Jr. Memorial, a modern animal house, was built and equipped in the barn on the property where the President of the College formerly lived. This was partially financed by a gift from the New Hampshire Medical Society of $3,000 and has met the demand of the various department for research facilities.

Close integration with the College has existed since the start of the School, as shown by the teaching of medical students in the laboratories of biology and chemistry. Also, the system has been used in reverse. As far back as Dr. Smith's days, college juniors and seniors were allowed to take the courses in the Medical School, chiefly because of the fact that there were few electives in the College, and because of the outstanding teaching qualities of Drs. Smith, Perkins, Mussey and Peaslee, who taught at various times until 1868. This was one of the reasons for the long list of non-graduates of the Medical School during those years.

Another factor that today is a "must" in every four-year medical school is a hospital. As was said before, students of medicine took their practical work with preceptors during that part of the year not given over to lectures, but it was early recognized that hospital teaching should be an essential part of medical education. The earliest reference to a hospital in Hanover, aside from the "pest houses" which treated epidemics of smallpox, is in the School advertisement of 1824. Whether there were others or-not, I have been unable to discover. Operative procedures during this period were performed in the lecture room of the old building on the same table on which, an hour before, cadaver demonstrations had been carried out. Patients were then transferred by wagon to houses about town for their convalescence. Records of these procedures are sadly lacking, but in the diary of Cyrus Parker Bradley of the Class of 1837 there is direct evidence of the operative work carried on at that time. As a junior in college, not registered in the Medical School, he attended lectures and operations in this room and he gives detailed operative descriptions which would do credit to a present-day medical student or interne.

In 1844 the medical faculty recommended to the trustees that they fit up the Franklin House as an infirmary for the gratuitous treatment of patients. No action seems to have been taken on this petition, but at about this time, possibly in the same year, Dr. Dixi Crosby, Professor of Surgery, purchased the house on College Street opposite the driveway to the Medical School, and until his retirement in 1870 conducted a hospital there, presumably doing major operations at the School and transporting patients back to the hospital. Following the closing of this institution there was no building used as a hospital until the opening of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in 1893. At its opening, it was considered to be the last word in. hospital construction, and gave much needed facilities for medical school teaching. The story of the hospital is a separate one and yet as the teaching hospital for the School, the part it has played and still is playing is priceless.

The financial and academic relationship of the School to the College for over a hundred years appears as most extraordinary. Beginning with Dr. Smith, the Trustees have always elected the members of the faculty. Dr. Smith was paid by the College various sums for his own salary, and granted small sums for expenses in his department; and in 1804 he was granted $200, provided he made his permanent residence in Hanover. The tuition in 1798 was $51 and whoever taught the various subjects collected this at his own risk from the student. In 1819 the College Treasurer collected the medical students' fees if requested by the professor, but at the latter's risk. The President of the College, who presided at faculty meetings, received half of the graduation fees, which varied from fifteen to twenty-five dollars from each graduate. Tickets were given to each student, and the general rule was that he had to present a ticket to each of the instructors. From 1838 on, until the College Treasurer took charge, all professors were paid by a division of fees received from the students. The account books, as far as they can be found, contain very meager information but at one time the division was thirtieths of shares, on just what basis it is difficult to judge. Salaries were always a source of considerable irritation, particularly to those members of the faculty not in residence, and at one time the problem was summed up in a letter which said, "Life is too short, to unravel your methods of bookkeeping." The collection of fees from students was an uncertainty and there were always outstanding notes. Rules were made refusing the granting of the degree if half of the graduation fee was not paid. Notes outstanding from 1841-1845 were $3,100.33, although in that same year the Secretary reported "that at the time of the examination of the Treasurer's accounts the faculty were free from all debts, that all incumbrances of past years have been liquidated and the affairs of the Faculty brought into such a condition that the future financial concerns can be conducted with comparative simplicity and ease." However, two years later an entire faculty meeting was taken up with an explanation of the outlawing of notes by Daniel Blaisdell, the College .Treasurer. This condition existed until 1901, when, after prolonged discussions between President Tucker and the medical faculty, it was voted that Dr. Gilman D. Frost act as Treasurer of the Medical Faculty under the direction of the College Treasurer. In 1904 "the Treasurer of Dartmouth College became the Treasurer of the Dartmouth Medical School."

For many years the President of the College was the presiding officer of the medical faculty and a member of the faculty served as Secretary and usually Treasurer. There was no "Dean" until Dr. C. P. Frost's name appears in the catalogue of 1873; his stationery carries that title, although there seems to be no record of his election by the Trustees. At Dr. Frost's death in 1896 Dr. William T. Smith was nominated by the faculty and was duly confirmed. Following his death in 1909, Dr. John M. Gile was Dean until 1935. Following his death, Dr. C. C. Stewart acted in this office for two years until 1927, when Dr. John P. Bowler was appointed and continued in this office until succeeded by Dr. Rolf C. Syvertsen in June 1945. In the years up to 1844 very little information can be found in the faculty records, which consist mostly of lists of matriculants and a very meager record of their accounts with the School. After this date the records seem to be fairly complete. Meetings were held at very irregular intervals, and as the nonresident lecturers became more numerous, many faculty decisions were made by mail votes accompanied by comments which serve as the historical material of this period.

For the first one hundred years, therefore, the School was run practically as a private institution, chairs being added in various departments as specialties were developed. The lecture term varied at different times from ten to fourteen to sixteen weeks, and back to fourteen. The. men who taught were widely known, many of them teaching in many schools; Dr. Mussey, for instance, in four other schools and Dr. A. B. Crosby in five others after having refused professorships in two more. At the same time the men located in town acted as preceptors for students through the rest of the year, Dr. Nathan Smith apparently having as many as eight or ten students at one time. Requirements for admission varied considerably but a high school education "or its equivalent" was about as advantageous as a college diploma. The School was widely publicized throughout New England in paid advertisements in newspapers. From 1877 until 1883 "Dean" Frost was the only resident member of the faculty and except for the short term in the fall, when the lecturers were here, handled all the medical practice and did all faculty business by mail. As early as Dr. Nathan Smith's time he and Dr. Cyrus Perkins with the aid of the

New Hampshire Medical Society worked to put down quackery. In 1820, probably at Dr. Mussey's suggestion, delegates were sent each year from the Society to quiz candidates for the degree of M.D., and in 1870 the Vermont Society did the same. This continued until 1910 when it was considered that the requirements of the state laws made it no longer necessary. In 1897 the first bill, with any teeth in it to control the practice of medicine was passed by the state legislature. President Tucker, the New Hampshire State Medical S ociety, and the members of the faculty aided in the initiation of this bill despite the fact that it was to bring about far-reaching changes in the set-up of the School. This law was based primarily on the New York State law and called for not less than four years of nine months each of medical study, but did not essentially change the premedical requirements. For this reason a so-called combined "lecture" and "recitation" course was devised, the latter to be run by the resident faculty, and in 1898 the new plan was put into operation.

Too much credit cannot be given to President Tucker for the changes for the better which were rapidly taking place. Early in his presidency he took under advisement the anomalous position of the School and decided the condition should not continue. There had for sometime been dissatisfaction among some of the "non-resident" members of the faculty, who resented this title. Dr. Tucker's proposal that the College take over the management of the School raised questions as to salaries and tenure of office in the minds of some, but the situation was finally ironed out satisfactorily. In 1898, equipment of a laboratory with microscopes at a cost of approximately $1500 was carried out, an instructor in histology, bacteriology and pathology was obtained, and in 190 a a physiologist who could give both didactic and laboratory instruction in that subject was added to the faculty. Again seniors in college were permitted to register for basic courses in the Medical School, the College receiving the tuition fees. In 1901 a branch of the New Hampshire State Board of Health was established at the School which gave the hospital and practitioners in this area a local service of much benefit and brought more material for teaching purposes. During the next few years teaching in Diseases of -the Skin and Orthopedics was begun by special lecturers.

In spite of these changes for the better, rumblings of distant thunder began to be heard, and 1897 Dr. Phineas Connor states in his Historical Address that "an assured past does not guarantee a certain future." He went on to say that in his belief, with the trend of modern medical teaching toward more clinical application, Hanover with its very limited facilities for such could not hope to compete with the urban schools and their large hospitals. He also said, as Nathan Smith did in 1810, that the difficulty of securing legitimate anatomical material was a great detriment to any future development. Again in 1901 he wrote that the School had no reason for existence as a graduating institution, that it should confine itself to the first two years, and that they should be taught by "medical men, not doctors of philosophy or bachelors of science, men who know from personal experience what everyone should know who has to deal with the ills of human beings, not of dogs, nor rabbits, nor oysters." In the same year Dr. Mundé states the same opinion. In letters to Dr. Tucker, other men voiced considerable question as to the four-year school, but gave very definite ideas as to changes in courses, the addition of courses, and emphasized the fact that money was needed and that the whole control of the School should be under the Trustees of the College. However, the President and faculty felt that the additions to the teaching staff and the small but growing hospital with its increasing clinical material warranted continuing the four-year course.

In 1906 the faculty received a letter from the Council of Medical Education of the American Medical Association . with certain recommendations. The consensus of the faculty seemed to be sympathy with the Council on any forward movement but not readiness to accept "the recommendations of the Council."

To go back a little, we must remember that a background of a liberal arts degree, or courses leading toward that, were not required for future physicians; but, as a matter of fact, of the first sixty men who received an M.8., forty percent held such a degree, whereas of the slightly more than eighteen hundred who received an M.D. through 1897 only twelve percent held a college degree. Dr. Tucker, in 1908, feeling that such a large group of men in a professional school with no undergraduate training lowered the general standing of the college community, recommended to the faculty of the School that at least two years of undergraduate work be required for admission. The faculty were unanimous in accepting this and after a considerable amount of study it was recommended to the Trustees that (1) two years of college work be required for admission to the Medical School, (2) a course be arranged in the college preparatory to the Medical School, and (3) that the degree of A.B. or B.S. be given at the end of four years, and an M.D. at the end of six years. It was finally arranged that candidates for the B.S. could enter Medical School at the beginning of the junior year and candidates for the A.B. at the beginning of the senior year, the difference being that candidates for the A.B. could not get their required subjects in freshman and sophomore years. The arrange- ment of these courses was voted in 1908 as the first concerted action by both faculties and went into effect in 1910. At this time the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching conducted an "independent" inspection and consequent rating of medical schools, and in the spring of 1910 the School was visited by Mr. Abraham Flexner, its representative. He made specific criticisms, chiefly that the Department of Anatomy should be filled by a full-time teacher, that the clinical facilities were too small (they were 80% surgical) and full use was not made of the material available. The School was rated "A" by the Council, and the work of the first two years was considered commend- able. A full-time teacher of anatomy was secured in 1911, thus fulfilling one of the demands made by the Council and giving a minimum of six full-time teachers. The situation here was no different than elsewhere in the country. Between 1904 and 1912 sixty-five colleges had been closed by merger or otherwise, and at the same time there was a decrease of 9,730 medical students. The total number of graduates in 1912 was 1,264 less than in 1904, mostly due to the closing of the "substandard" schools. Formal application was made for renewal of membership in the Association of American Medical Colleges at the direct suggestion of the Chairman of the Council on Medical Education, but neither that year nor the next was an inspection made and therefore no definite action resulted.

The year 1913 seems to have been a hectic one. Unless something more radical than seemed possible was done with its last two years the School was going out of existence or, as Dr. Connor prophesied in 1902, it would "die of dry gangrene." The question of whether the School would be rated by the Council as an "A" school in another year had arisen, and it had not yet been re-admitted to the Association of American Medical Colleges. Plans were discussed by which third and fourth year men might go to one of the large Massachusetts State Hospitals or might link up with one of the city medical schools. None of these propositions was received favorably by the faculty, and it came down to a matter of going on as was or omitting the last two years—a question on which the faculty never reached agreement. With all these factors in mind, the Dean felt that there would be loss of students to the vanishing point. Others felt that the only way to find out was to try. One prominent member of the faculty felt that "any line of reasoning that points to the conclusion that we had better at once give up clinical teaching and our degree conferring power can be advanced with equal force to justfy suicide as against the chance of a natural death, and suicide in almost all systems of morals is rated as a sin, in all systems of law as a crime." Finally, on April 26, 1913, the Trustees voted "after the year 1914 instruction pertaining to the two last or clinical years of the course in Medicine be suspended for the present, and that the resources of the School in teachers and equipment be concentrated upon the first and second years of the course which may be elected by undergraduates of the College."

Thus ended what might be called the second era in the history of the School. In all ways the School was stronger for the struggle, the departments in the first two years were augmented, and the way was shown to continued improvement in the future. All of the teaching could now be done by men on the ground, the arrangement of courses and lectures for the "non-resident" faculty was eliminated, the hospital was abundantly large for the teaching of the first two years, a sound schedule in connection with the College had been arranged, the requirements for admission were on a par with those of other schools in the country, and it was still rated as Class A. As one looks back at that period, it seems that there must have been a general feeling of relief on the part of everyone who had had anything to do with the developments.

During the next few years more ade- quate quarters were provided for, the teaching of Pharmacology and a full-time bacteriologist was added to the staff. Minor changes were made in regard to admission which tightened the rules. The School was rated by the Council in the first group of schools under Class "A" requiring two or more years of college work for admission. For three years following 1914 the classes ranged from five to nine men each, following which the numbers jumped rapidly to fifteen or eighteen, and in recent years the classes have been limited to twenty-four only, because of the size of the physical plant. In 1917, the faculty passed a ruling that no medical school credit should be given a student until he had ceased all participation in undergraduate activities such as athletic teams, musical and dramatic organizations. Three years of college work and a minimal scholastic average were made a prerequisite for admission.

In 1920 and 1921 there began to be considerable discussion of the supply of physicians and the average age of men practicing in New England, particularly in New Hampshire. Papers by Drs. John M. Gile and Frederic P. Lord went into detail as to the number of graduates, new licenses being issued, and the comparative ages of practitioners in rural and urban areas. There was extensive discussion in the New Hampshire Medical Society as to the possibility of the reestablishment of a four-year medical school in New Hampshire, and particularly at the School in Hanover. The faculty in 1925 voted to ask the staff of the hospital to consider plans for enlargement as it seemed that on the future of the hospital depended the expansion of the School as a graduating unit. In 1924, the Secretary of the Council on Medical Education had requested that more students be taken into the School. In 1927 the New Hampshire Medical Society had more discussion as to the possibility of a four-year course, all based on the fact that the proportion of doctors to population was dropping, that the average age of practitioners was rising, and that men trained in the city schools were not returning to country practice. In 1927 a special committee of the New Hampshire Medical Society made another study of the whole situation in New Hampshire and recommended definitely the need of a four-year medical school in this state. At that time the lack of funds and sufficient teaching beds was still considered detriment enough to prevent any move.

In 1925 the School received an invitation to send a delegate to the meeting of the Association of American Medical Colleges. In 1926 an inspection of the School was made, and in November of that year it was readmitted to membership. Since that time the School has participated actively in the affairs of the Association and the Dean has served on the Association's Executive Council.

With the limitation of the curriculu in 1913 to the two-year course the question of transfer of students for the final two years was automatically raised. This prospect was viewed with what proved to be unwarranted apprehension, for the small classes and the exacting requirements for admission made our men eligible, by their preparation, for any school in the country. Cordial invitations for our students were received from sixteen of twenty-three schools interrogated in regard to transfer. Since that time no man transferred by us has failed to graduate from a Class "A" school and these degrees have been given in schools from coast to coast. Reports from these schools indicate that the men stand well in their respective classes. Further evidence is shown by the results of the examinations of the State Board and the National Board of Medical Examiners as well as the reports of the men themselves as to their pre-clinical preparation.

The development of the Dartmouth Eye Institute as a result of the research conducted by Prof. Adelbert Ames and his colleagues has brought to the Medical School a notable phase of activity which has been something separate and distinct from undergraduate teaching.

In passing it is interesting to note that the Alpha Kappa Kappa Medical Society was founded here in 1889, later developing into a national fraternity with Dartmouth as the Alpha chapter. Also of considerable interest is that Dr. Edwin Frost in 1896 developed X-ray plates shortly after Roentgen's first publications. On February 3, 1896, he made an X-ray photographic plate of a fractured forearm—said to have been one of the first, if not the first, plate for clinical purposes in this country.

The Medical School, like the College and other associated schools, has been under an accelerated program since 1942, with the addition of the summer term. Classes include Army, Navy, and civilian students. There have been' modifications in the requirements for admission corresponding to Army and Navy programs but not in the curriculum. The whole plan is arranged to get medical men into the armed forces as soon as possible, and has been entered upon purely as an emergency measure. Whether the time-saving factor will be continued in future schedules is doubtful.

The evolution of the School from Dr. Nathan Smith's one-man institution to the present has been one of steady growth. As one goes back over the story, it is hard to say what has been the chief factor influencing the evolution of medical care in Hanover from a lone resident physician and head of the School in 1878 to the coverage of practically every special field in medicine at the beginning of the present war. The hospital approaches the two-hundred-bed capacity, which in 1913 was said could never be attained. Teaching at the autopsy table, a demand which was said in 1913 could never be met, plays an important role in the present curriculum. There is still present the ageold dearth of material for dissecting purposes: one of the reasons for Dr. Nathan Smith's leaving Hanover, again brought to public attention by Dr. Connor in 1897, and now a condition alarmingly general over the whole country.

At the present time there is no intended change toward a four-year school with the resumption of the granting of the M.D. degree, but with the increased capacity for clinical teaching and the great demand for more medical graduates each year, it is entirely within the realm of possibility that such an eventuality might occur. The groundwork is well laid and only the future turn of events in the world of medical teaching and practice will provide the answer.

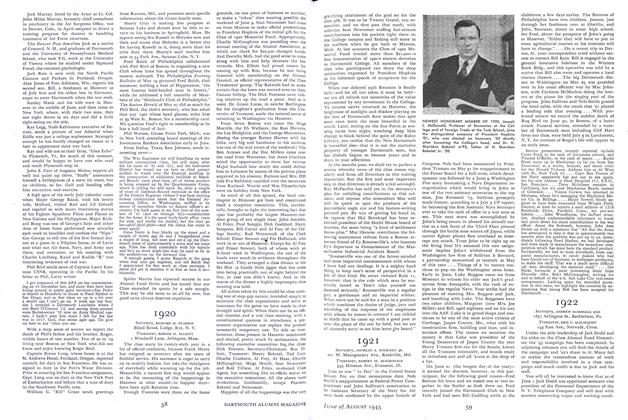

THE OLDEST ORIGINAL CLASSROOM .BUILDING ON CAMPUS, the Old Medical Building at the right was built in 1811 with funds voted by the state legislature. The Nathan Smith Laboratory to the left was erected in 1908 through gifts from alumni and friends of the School in honor of its founder.

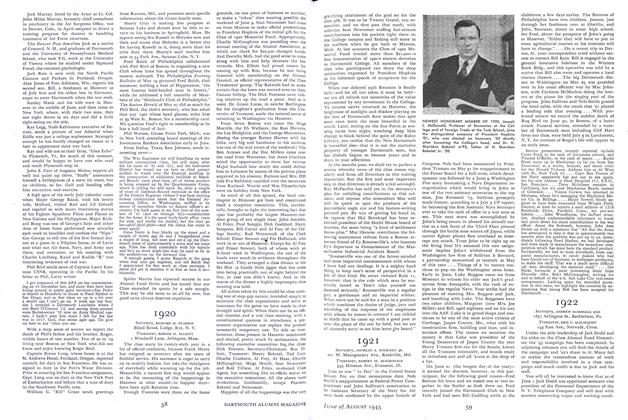

DR. NATHAN SMITH, founder of the Medical School, as he appears in a portrait owned by Yale.

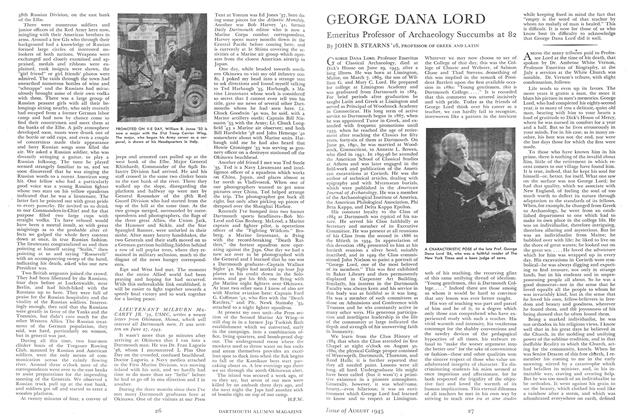

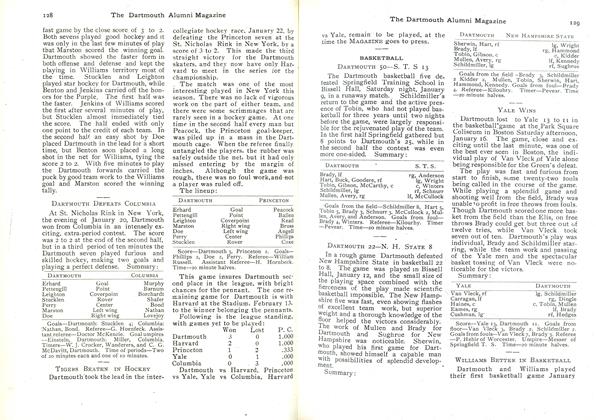

THE MEDICAL SCHOOL FACULTY TODAY. Left to right, front row—J. B. McKenna, A. E. MacNeill, J. F. Gile '16, Dean R. C. Syvertsen '18, J. P. Bowler '15, F. P. Lord '98, P. Bartlett 'oom, H. N. Kingsford '98m, E. H. Carleton '97 m, C. E. Bolser '97. Second row—S. M. Gundersen, J. J. Boardman, L. K. Sycamore '24, K. N. Atkins, C. J. Campbell '17, C. C. Stewart '23, H. T. French '13. Third row—J. H. Fofley, W. C. MacCarty '33, J. Milne '37, J. P. Maes, J. F. Crow, J. A. Murtagh, W. L. McLaughlin '37. Back row—C. F. Breisacher, W. A. Ellis, R. K. House, R. H. Barrett. Other faculty members not shown in the picture are W. W. Ballard '28, H. L. Heyl, G. A. Lord '30, J. S. Lyle '34, A. Mather, R. E. Miller '24, and T. S. Potter. Absent now in military service are F. H. Connell '28, J. A. Coyle '24, R. W. Hunter '31, N. T. Miliiken, R. C. Tanzer '25, and M. D. Tyson.

LABORATORY WORK FIGURES PROMINENTLY in the life of a medical student. Here are some of the second- year class of Dartmouth Medical School in the Nathan Smith Laboratory.

EX-DEAN AND NEW DEAN. Dr. John P. Bowler '15 (left), who recently resigned as Dean of the Medical School, chats with his successor, Dr. Rolf C. Syvertsen '18, who was Secretary of the School for 20 years before being named Assistant Dean last year. Dr. Bowler continues on the faculty as Professor of Surgery.

INFORMAL POSE BY THE AUTHOR. Dr. John F. Gile '16, Life Trustee of the College and Medical School professor, who wrote this article, snapped on one of the hunting trips which are his hobby. His father, Dr. John M. Gile '87, a famous north country physician, taught on the Medical School faculty for 29 years, was Dean from 1910 to 1925, and also was a Life Trustee of the College.

THE MEDICAL SCHOOL STUDENT BODY AT PRESENT IS A MIXTURE OF ARMY, NAVY AND CIVILIANS, WITH SERVICE MEN PREDOMINATING.

PROFESSOR OF CLINICAL SURGERY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleINFANTRYMAN'S BOS WELL

August 1945 By LYNN CALLAWAY '38 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

August 1945 -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1945 By H.F.W. -

Article

ArticleMedical School

August 1945 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

August 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

Article

-

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

January, 1909 -

Article

ArticleTHE PLAYERS

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleChanning H. Cox '01 Gives Fund to Support Dartmouth's Libraries

MAY 1966 -

Article

ArticleSnooze Control

May/June 2004 -

Article

Article"L. B." As a Teacher

December 1951 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE MEN IN POLITICS

April 1944 By DAYTON D. McKEAN