As part of the United States' victorious Navy, Lt. Lincoln Daniels '34 returned to Japan 10 years after his first three months' visit to the islands as a tourist. In the above article he gives his impressions of the reactions of the Japanese people he met to their defeat. The lieutenant was on the Dartmouth swimming team at the College and majored in Economics.

Our transport entered Tokyo Bay the morning of October 4 to debark troops carried from the States. We passed several of our battle ships on the way in, and many destroyers and destroyer escorts rode to mooring buoys in nests of three or four inside the breakwater. Their presence was reassuring. We felt strange approaching a dock on the Yokohama water- front when a short time ago we had sought protection from Jap bombs under a blanket of smoke as we lay off Okinawa. All of us had become reconciled to fighting our way into Japan, yet a smiling Jap pilot was on the bridge guiding our ship to its berth. I knew from my previous visit to the country that the Japanese were masters of ingratiation and I suspected that they had reverted to this role with the cessation of hostilities. They have an amazing capacity for effecting quick changes, suggestive of the skilled impersonator who can create the illusion of several personalities within a few minutes.

The first few hours ashore convinced me that the people are not bitter over their defeat. One would expect a conquered people to be sullen and non-cooperative. On the contrary, they are friendly and eager to help. Their attitude, whether or not it is sincere, has certainly simplified our problems of occupation. This fact should detract no credit from our forces which have given a fine demonstration of Christian ethics, of which we can well be proud, in their treatment of the defeated Japanese.

The occupation has proceeded without incident or violence. It is gradually fanning out from cities into the rural areas. Our high command orders all firearms, ammunition, and other implements of war within a specified area gathered in stockpiles by a given date. The local constabulary is directed to clear and prepare adequate buildings to serve as quarters for our soldiers. The Japanese are complying with these orders to the letter. In fact, they have proved so docile and cooperative that we probably won't occupy as extensively as first planned. The actual enforcement and administration of orders emanating from our High Command is effected by the Japanese. The use of coercion has been avoided from the start.

Our soldiers manifest the usual interest of visitors to a foreign land in souvenirs. Swords, firearms, and silk kimonos' are the most coveted articles. No matter how anxious a soldier is to acquire a souvenir on display in a shop, he will not appropriate it without proper payment. If he cannot inveigle the shop keeper into selling for the price he can afford to pay, he leaves like any disgruntled shopper. His just and considerate treatment of the Japs in small dealings is truly remarkable. If the owner of a kimono won't sell for the price offered, this is his prerogative. We are neither stealing nor using force to acquire what we want. If there was looting in the first days of the occupation, it was quickly suppressed.

As T walked and rode over the devastated Tokyo—Yokohama area, and out into the country, I was approached several times by Japanese youths who knew a little English. The war has not lessened their interest in our language, and they seize every opportunity to practice it. One boy remarked, "American soldier so big. Japanese soldier so small." This unguarded observation acknowledging a sense o£ inferiority is typical of how the common people really feel about us. They have always been in awe of us. I was conscious of this when I visited the country ten years ago. Our victory has served to deepen this feeling. I think, more than ever, they regard us as fabulously rich, productive, and powerful. The realization that it was foolhardy of their leaders to have provoked war with us is clear in the adulatory look which comes into the faces of the women and children when our strapping soldiers move amongst them. Certainly, if the derision rested With the millions who till the soil and work the factories we need not fear another war with Japan. Of course, this class has had no voice in the Government. To uproot oligarchy, and replace it with some form of democracy so that the masses can make known their will is a tremendous challenge to the ingenuity and perseverance of the occupation experts.

"Goodbye. I have enjoyed our talk very much. I hope you will always be happy." This was the parting remark of another boy as he left me in a train full of Japs, when I was travelling to Kamakura. You can't help feeling friendly towards one who expresses these sentiments. Vicious and cruel in war, but gentle and decorous in peace—this is the enigma of these people.

I had an opportunity to talk with a wealthy and prominent Japanese educated in the United States and England. There was no language barrier between us, and he seemed to give honest answers to my questions. His opinion concurred with mine: that neither the Emperor nor the diplomats negotiating with Hull were informed as to the timing of the strike at Pearl Harbor. They knew, of course, that the attack was blue printed, but they may well have been kept in the dark as to when it was to be ordered. He maintains that up to the Moment of the attack, pacifistic elements in the government labored to preserve peace with the United States.

It is probable that our use of the atomic bomb shortened the war by six months. The militarists directing the war knew that it was lost last spring. However, they planned to prolong resistance until the end of 1945, all the while seeking favorable peace terms through neutral channels. Russia's declaration of war against them was a severe blow, but this informed Japanese feels that his country would have fought on had we not used the atomic bomb.

He made an interesting observation on the prevalent feeling among the common people about Japan's defeat. Again and again he hears them in trains and street cars saying that the defeat is a good thing for Japan. The militarists were deluded into over-confidence. They believed that their military machine was invincible. Only through defeat could they be proven wrong, and driven from power. I am inclined to credit this belief amongst the masses. If they welcome the humiliation and deprivations of defeat as the price to be rid of the military despots, there is great promise for the future of Japan.

We must not be beguiled by the apparent friendliness of the Japanese. We should remain skeptical until they prove over a considerable period of time that they are sincere in their desire to live peacefully. The younger generation can be educated to pacifism rather than war. We have made a noble start in the right direction by our humane and just treatment of a beaten foe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

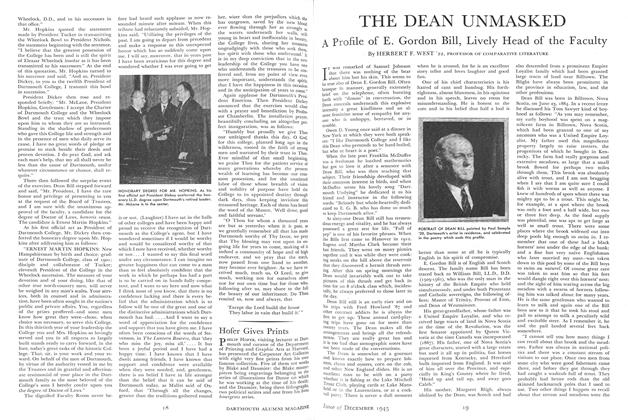

ArticleTHE DEAN UNMASKED

December 1945 By HERBERT F. WEST '22, -

Article

ArticleTHE VETERAN RETURNS

December 1945 By PROF. Wm. STUART MESSER, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

December 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS, JOHN W. CALLAGHAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

December 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT DICKEY INDUCTED

December 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH ELECTIONS

July 1919 -

Article

ArticleA New Twist For Picking Roommates

May/June 2007 -

Article

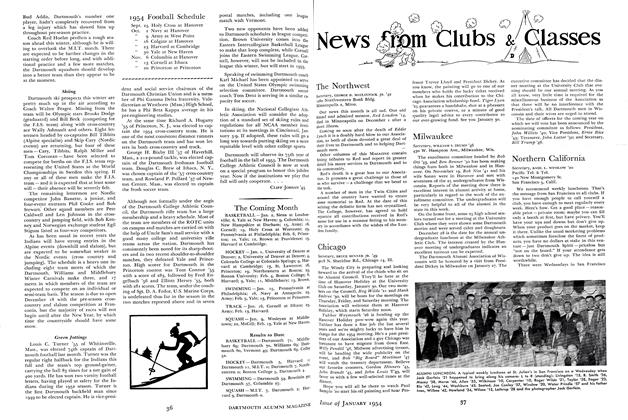

ArticleBASKETBALL

APRIL 1968 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

ArticleGreen Jottings

January 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleSKIING

APRIL 1969 By JACK DE GANGE -

Article

ArticleTuck School

April 1951 By K. A. Hill, H. L. Duncombe