Campus in Earlier Conflict Contrasts with Today's

EARLY IN MARCH iB6O Thomas Noyes Chase said goodbye to his fiancee at ' some Massachusetts depot and took the train for White River Junction. Although he was entering Dartmouth College as a junior, he was returning to a beloved country and his chosen college. Two years earlier he had graduated from Thetford Academy, passed the Dartmouth entrance examinations, and then suddenly elected to attend Amherst, "to escape," as he wrote in one of his letters, "from my old associates." Nor was he exactly an untried young man. Like so many scholarly youth of his generation, he Used the winter vacation and short winter term of academy or college to teach school and already, though hardly more than a boy, he had to his professional credit success in at least five different districts in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. One of his letters of recommendation announced,

"There being no escape from his discipline at the first moment, pupils who had been giving others much trouble forgot their tendency to mischief in the enthusiasm inspired and were only aware of the benign authority that followed....Furthermore he already had friends, Thetford Academy acquaintances, at Hanover, two of whom met him at the Junction. Still the prospect that March was far from pleasing. He had to take entrance examinations for the third time and Hanover presented the conventional spring day; the ground, still covered with "a mantle of snow, which, however, it was trying to shake off & has since exchanged for a coat of mud." But he found rooms in a house near the campus, passed the examinations which proved much easier in actuality than in anticipation, and devoured the cake and apples with which his fiancee supplied him.

The next two years were a time of study. Since he still elected to teach from mid- November to February, he had to make up the lost classes in the terms when he was present from March until August. To master the missed courses and keep abreast of the current Junior and Senior work in "physics," a covering term for all science from astronomy to geology; in philosophy —Edwards' On the Will, Paley's Evidencesof Christianityrhetoric "themes and declamations"; Latin, Greek, and a smattering of government and political economy, required each day three hours in the classroom and six hours outside. But this vigorous regime was made lighter by some good teaching. With the eye of an already experienced teacher, he appraised John N. Putnam, Professor of Greek: "Prof. Putnam is my model teacher. He conducts a recitation as quietly as possible, speaking in quite a low tone of voice, always asking questions right straight along in the same manner, whether the student answers or not, answering them himself after waiting a proper length of time, except when he thinks there can be no reason for their being missed, when he lets them go un- answered. This is his only reprimand & a student don't feel a real scolding from another Prof, half as deeply." He finds little time for reading. He dutifully traversed printed sermons and sentimental novels of mingled romance, incredible coincidence, and theology which his Acton miss sent him. He himself took from the library Married or Single to "dream over." In more serious moments he samples Bancroft and Dickens. The latter he observed is "truly diffuse. His gems of thought are buried beneath much rubbish Nicholas Nickleby I embraced—with one arm . . . . and Dombey and Son has thrown me into a relapse."

There was not much college life. The fevered and transient friendliness that accompanied fraternity pledging amused him. "New friends too swarm about me like flies about a drop of honey, but after the honey has disappeared, then the bees fly away. .... I haven't pledged yet but I guess I shall join the K K K's." For student pranks he had little tolerance; perhaps his teaching experience had already aligned his loyalties with the faculty. Apparently he felt, however, some sympathy when in 1862, "Our class is getting into another jingle with the Faculty. The Seniors have usually had a holiday-week during this term to write their pieces in, which the Faculty refused to grant this year, as they also did last. At a class meeting today 31 pledged themselves to take this week without leave." He fell back for excitement upon the courtship and marriages of his friends, largely his Thetford ones. The old Academy, like most of its types, was an unexcelled matchmaker. The note is sounded in his first Dartmouth letter: "Under the influence of that peculiar magnetic attraction, we used to hear about, Walker & Patch have been wont to make journeys up the valley of the Connecticut occasionally ever since they have been in coll. So, you see, if one is the victim of Cupid's power, he needn't feel that he is alone." And his Senior year he was much concerned with the troubled love affairs of his roommate, George Patch. "He has written two letters and some lines upon the New Year to his Miss Thetford, of which she has taken no notice & he says Secessia may eat up the Stars and Stripes before he will write again or go to see her."

1860 ELECTON CREATED EXCITEMENT

After all, Chase's first year at Dartmouth coincided with the heated election of 1860 and the success of Abraham Lincoln and the young Republican party, with the firing upon Fort Sumter and Bull Run, and the last months of his Senior year—the summer of 1862—saw McClellan fight eastward along the Peninsula to Richmond in a campaign apparently at first victorious and later a failure. All these stirring events find little reflection in Chase's letters. Although sympathetic to the Northern cause, like many other young Northerners later famous in business, politics, or scholarship, he felt no personal responsibility for participation. Nor was the general atmosphere of the Dartmouth campus likely to shatter his detachment. Nathan Lord, a Bowdoin graduate and then Dartmouth's president, was one of the most prominent pro-slavery men of the North and eventually so unpopular with Northern zealots that he had to resign his position. Naturally, therefore, Boston, when Chase visited the city in his May vacation of 1861, presented a martial contrast to Hanover. On the green Com- mon along, with baby carriages and spoon- ing couples, there was a "company of troops drilling," and an immense crowd gathered about the station and the streets to see two regiments from Maine pass through. From Hanover he was writing a week later, "Patriotism seems to be at ebb tide here now. This morning the old President made a very soothing speech &: as usual managed to talk half an hour without defining his position." But a year later the College Bell was ringing to celebrate McClellan's earlier victories. Then, When the good news changed to bad and Lincoln called for three-months volunteers, the first war excitement hit the campus. On June 18, 1862, Chase wrote, "The Dartmouth Cavalry are leaving tonight, in honor of which the Norwich Cadets are firing cannon. A member of the Junior Class has recruited a full company, about thirty of whom are students here. They go under Gov. Sprague (of Rhode Island) for three months According to newspaper accounts of to-day they will be needed I'm afraid it will be a long time before the rebels will acknowledge themselves beaten." Perhaps an inducement, additional to serving their country, influenced some of these volunteers. "Those who have gone for three months will receive their diplomas with the rest of their classes," Chase added in a letter a week later.

But by this time. he was at the happy summit of his Senior year. When he had come to Dartmouth, he confided to his fiancee that he was resolved to become a man, a scholar, and a Christian. Undoubtedly the fulfillment of this first am- bition was the result of growth more than of appraisal and effort. As for scholarly attainment, he feared that the "Phi Beta ship" might spread her sails too far ahead for him to catch up. But at the end of his Junior year he was writing with visible pride, "You didn't ask me in your last whether I was a Phi Beta or not, so I'll be good & tell you. Yes, my dear, I'm a 'stiff' Phi Beta & our Phi Beta mark is much higher than that of any other class in college or of the one that just graduated; so you see I'm a little above the average in scholarship, tho' I'm not in height." This jubilation over good grades, however, was not accompanied with election to the Society. But as for being a Christian, that was at once a more complicated and more insistent business, for his fiancee, of whom one of young Chase's friends had once said, "She is too pious for me," insisted that her husband match her religious belief. Apparently he at last satisfied her of his Christian state but still he was confessing, "I wish I was less practical & more poetical,that my imagination would picture out heaven to me so that I could live there sometimes. I can never make a heaven that pleases me. When I find the site of it, I begin to calculate how many miles it is from the earth; then how many can walk into the pearly gates abreast; then how many layers of oblong stones the walls are in height; then how many cwt. of gold there is in the throne. In fact I get so absorbed in my mathematical calculations that I can't see Christ at all."

But such speculations died away in the swift, pleasurable urgency of the last Senior weeks. There were Senior pictures—"l send a picture I had taken yesterday for you to criticize. What suggestions would you make in reference to the posture of the body, the position of the head, arrangement of hair, &c.? Some of the boys are having themselves standing & some sitting." There were undergraduate friendships, ripening and soon to be broken. Of Patch, a roommate once of mere convenience, he was now feeling, "We had assimilated wonderfully. .... Last term & this we have been separated from each other scarcely an hour. Indeed, we were often spoken of by other students as the Siamese twins, & as we sat on the bank of the river the other evening I hailed a boat that was passing by, when one fellow in the boat asked, 'ls that Chase or Patch'—another one said, 'lf it's one it's tother & if it's tother it's one.' " Then finally like so many Dartmouth men, he yielded to the lure of Ascutney whose many moods dominated the valley to the South. "We walked from here to the top of the mountain 22 or 3 miles in a day. We first went to W. Windsor to see an old Amherst acquaintance, who had given us an invitation, thinking of stopping there over night, but not feeling tired & wanting to see the sun rise from the mountain, we concluded to take some blankets & pass the night up there, in the little stone hut built there for the convenience of those who go there. Arriving at the summit just before dark we found two ministers & ladies & some boys. They had a nice fire, some hot tea, which they generously shared with us & had made a fine bed of hemlock boughs. We passed the night pleasantly. The morning was clear & the sunrise was a glorious sight. As he shone upon the fog in the valley of the river, it rolled up like curling smoke making a picture of most perfect beauty. The view is extensive and varied & one of the ministers said it surpassed in beauty that from Mt. Washington & Katahdin. I was surprised at seeing so few cottages. They are most all hid under the hills. We enjoyed the scenery a few hours, then went to Windsor—visited the gun factory there & in the P.M. came up on the train."

HUNT FOR A JOB BEGINS

The problem of whom to invite to Commencement was dwarfed, however, by the finding of a job, for without a job Chase could not get married. He flirted with openings in New England and the West. On the whole most promising was the academy at Royalton where the school fund paid $150 a year and wood for the school and tuition might increase the total intake to $1000 if the war "should close." He described the institution and the village with somber realism. "The village is in White River Valley entirely shut in by the surrounding hills. The natives, as is natural, consider it remarkably pleasant, but I can't quite agree with them. It contains a hotel, bank, townhouse, a Congregational & an Episcopal church, the latter being small. & several stores, besides the Academy. This is painted a dark color, two stories, containing hall, recitation rooms, & study rooms. It is on the whole superior to the one at Thetford, though it is some- what out of repair inside & the settees particularly have been roughly used. The collection of houses is not great & many of them begin to show their need of paint. The community is quiet 8c the citizens are not difficult to be suited. The railroad running right thro the village injures the appearance & the noise of it isn't pleasant."

Four weeks after this letter, crammed with all its varied adventures and anticipations, came Commencement. His mother and father could not attend because, as the former explained in a letter of motherly advice, "At this season of the year, I must tend to the milk and your father has a great deal of work to do in taking care of his hay and grain." With the war help was hard to hire even at $2.00 a day. His fiancee decided to risk attendance, though earlier, whether because of Dartmouth's superiority or depravity, she had expressed a fear lest her contact with Commencement might "neutralize" her love for her betrothed. A compelling reason explained her presence. The day after Commencement, the couple, with a relation or two, drove to Thetford, where their favorite minister consummated with a wedding service still another "Thetford flirtation." Some months later they took up residence at Royalton where after two years of teaching, Chase, the Thetford and Dartmouth graduate and young husband, won the commendation of being "a successful teacher in our Academy" .... and "a man of unexceptional moral and religious character." Perhaps this latter equivocal estimate was a slip of the pen. Or was it a Vermonter's way of bestowing praise?

THOMAS NOYES CHASE '62-'"At graduation he was 5-feet, 8-inches in height, 150 pounds in weighthad auburn hair, chin whiskers, sandy complexion; smoked; was a Congregationalist. ..according to H. S. Cummings in "Sketches of the Class of 1862."

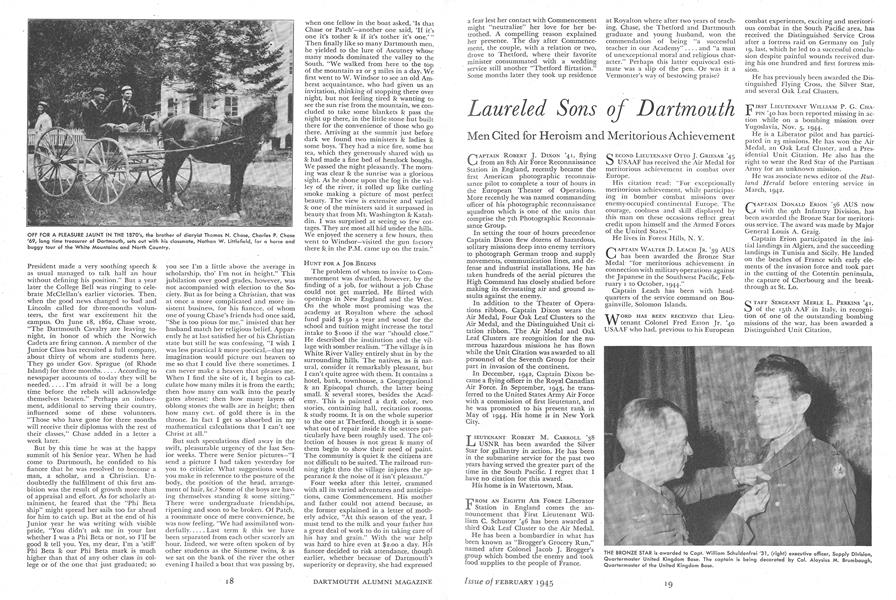

OFF FOR A PLEASURE JAUNT IN THE 1870's, the brother of diaryist Thomas N. Chase, Charles P. Chase '69, long time treasurer of Dartmouth, sets out with his classmate, Nathan W. Littlefield, for a horse and buggy tour of the White Mountains and North Country.

PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, BOWDOIN COLLEGE

Thomas Noyes Chase, Dartmouth 1862, and thus a classmate of Edward Tuck, taught through most of his life at Atlanta University. In 1872 a colleague facetiously described him as "a carpet bagger, a nigger teacher, an old Dart, boy, and a good fellow." A younger brother, Charles P. Chase, 1869, was for many years president of the Dartmouth National Bank and Treasurer of the College.

Professor Kirkland is the grandson of Thomas Noyes Chase and based his article upon his grandfather's undergrad- uate letters, which he recently presented to Baker Library. A summer resident of Thetford Hill, Vt., he is a frequent visitor to Hanover and is the father of Edward S. Kirkland '46.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE THAYER SCHOOL

February 1945 By PROF. WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28, -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Casualties

February 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1945 By JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

February 1945 By H. F. W.