Its Unaltered Aim Since 1871 Becomes "Modern" Policy

THE THAYER SCHOOL officially opened its doors in September, 1871, but it began its actual existence on July 9, 1870, at South Braintree, Massachusetts. On that day, Lieutenant Robert Fletcher, a 22-year-old instructor at the United States Military Academy, called at the home of Brigadier General Sylvanus Thayer. General Thayer was a graduate of both Dartmouth, in 1807, and the Military Academy, in 1808, and was known then, as he still is, as the father of the Academy in recognition of his record as Superintendent from 1817 to 1833.

ASSISTANT DEAN

When Thayer took charge of the Academy he found that the cadets, who were selected almost entirely on the basis of political influence, were not required to attend classes, undergo any appreciable military discipline, or maintain even a semblance of academic accomplishment. When he resigned his superintendency, the Academy had acquired a prestige in the world as an outstanding engineering school of the time and a high-ranking military institution.

With this academic background, which was followed by thirty years in charge of the fortification of Boston Harbor, it was natural that on his retirement from active service General Thayer should devote his energies to the founding of a school of civil engineering at his alma mater. His ideals were high and he knew that at his age the realization of such ideals could be accomplished only by placing the direction of his school in the hands of a man whose background was broad enough and whose per- sonal characteristics were such that he would be able to grasp the significance of engineering as a profession.

This was the contribution Thayer made in founding his school at Dartmouth. Engineering at the Military Academy was essentially military in nature, and in the civilian schools which had been established prior to 1870 engineering was taught as a trade. Here for the first time was a school for civilians based on the proposition that engineering was a learned profession.

Thus it was that the Thayer School really began when General Thayer found in Robert Fletcher a man who could understand the meaning of engineering as a profession and who could establish and maintain the school on this level. How well Thayer chose his man is demonstrated by the fact that Robert Fletcher was the director of the School for 47 years, and that in tribute to his work, Dartmouth College awarded him the honorary degrees of Ph.D. in 1884 and Sc.D. in 1918. As General Thayer is the father of the Military Academy, so is the man of his choosing, Robert Fletcher, the father of the Thayer School.

Public opinion has been slow to accept engineering as a learned profession, although the increasing importance of technology and engineering in twentieth-century life has made abundantly clear the obligations of scientific men to society. En- gineers who have attained positions of highest responsibility have recognized their work as a profession and have urged engineering schools to adopt this viewpoint in their teaching. Dean Roscoe Pound, emeritus head of the Harvard Law School, took as his thesis for a lecture on "Education for the Professions" in the Guernsey Center Moore series a year ago the proposition that a liberal arts education should be required preparation for students in the professions, including engineering. Similarly, on October 7, 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed an open letter to the engineering educators of the nation urging a fuller recognition of the "impact of science and engineering upon human life."

More recently, engineering educators throughout the country have expressed their personal convictions that engineering curricula must be provided with a broader base. But the record of engineering school policy bears out only too well the statement that "Good education is always ahead of public opinion and always behind the needs of the times." It is universally recognized that the technical demands of engineering education are so heavy that a four-year curriculum must devote itself almost exclusively to these subjects. Yet the Thayer School is the only engineering school in the country which has consistently required liberal arts preparation and a five-year curriculum for an engineering degree. Recently Cornell, under the presidency of Edmund E. Day '05, announced that it would require a minimum of five years for engineering degrees after the war.

This educational policy, which has kept the Thayer School in a class by itself until the recent announcement by Cornell, was concisely stated by President Hopkins in 1925. He said,

The policy of the Thayer School of Civil Engineering is based upon the theory that the purpose of an education is to give a man breadth and depth in his knowledge. In the field of Civil Enjgineering gineering, therefore, the educated engineer, under the policy of the School, must first of all have acquired the general culture which it is the purpose of a college education to give, and must then have superimposed upon this, specialized knowledge in regard to the scope of the field of engineering and the various facts which have to do with basic principles essential to a Civil Engineer. In other words, it is the purpose of the School to give to the college educated man knowledge of the fundamental theory and practice of engineering, but at the same time to induce him to see the relationship of engineering to life as a whole.

For this policy to be most effective, there should be a close coordination between the College where the student is expected to acquire breadth of knowledge and the Thayer School where he should acquire depth of knowledge without losing his broader perspective. Such coordination has been accomplished in the past in a number of ways. The first example occurred during the first years of the School's existence when it was found that graduates of Dartmouth were not prepared to satisfy the entrance requirements prescribed by General Thayer. This situation was corrected by modification of both the entrance requirements and the College curriculum. A similar adjustment in 1893 resulted in decreasing the total time required for graduation from Thayer School from six to five years. That same year, President Tucker in his Inaugural Address on "The Historic College" described the relation between the liberal arts college and professional study in these words:

It is always and everywhere the function of the College to give a liberal education, beyond which and out of which the-process of specialization may go on in any direction and to any extent. The College must continually adjust itself to make proper connection with every kind of specialized work, not to do it.

Guidance of students during their undergraduate years of preparation for the School has been based on the belief that pre-engineering subjects should not be permitted to encroach unduly on the liberal arts program. For this reason, prerequisites have been reduced in recent years, and this in turn has made it increasingly important that the required courses in the College "make proper connection with" the professional courses of the Thayer School.

It has always been our belief that the liberal arts program should precede the professional studies rather than parallel them as in some institutions. There are two reasons for this. First, when a nontechnical course is included in a schedule of engineering courses, the result is usually a lack of student interest in the non-technical course caused by a feeling that such a course is a side issue and has no real im- portance in the engineering curriculum. If, on the other hand, the liberal arts work precedes the professional studies it be- comes an essential part of the curriculum and the student regards it as a preparation for engineering rather than as a side issue.

The second reason is that by its very nature liberal arts education must go be- yond the classroom. The student must live with it. He must live among others whose principal interest is in liberal arts sub- jects. He must follow up the classroom and homework assignments with contempla- tion and discussion—in short, with bull sessions. Only in this way can the full broadening effect of a liberal arts educa- tion be acquired. Only in this way can the student acquire the maturity which en- ables him to master the professional sub- jects in two years of intensive study at the Thayer School.

An important feature of the Thayer School system which is believed to be es- sential to effective teaching of professional subjects was recently expressed by Dean Garran to his faculty in these words: "Engineering is alive and real. We should make it that way in our teaching. If a single student finishes a course in a fundamental subject without being aware of its applications to engineering work or without confidence that he can apply what he has learned to a useful purpose, I feel that we as teachers have failed." In die classroom, lecturing is avoided wherever the more personalized recitation method can be used. Instructors insist on maximum participation by students in classroom discussions. Visual aids are used as much as possible, including charts, slides, motion pictures, samples of materials, models, and instructor demonstrations. Where the nature of the subject matter is such that textbooks are not available, mimeographed notes are often prepared. Where this is not feasible, the lecture system must be used. In this case, emphasis is placed on methods of taking rough class notes and transcribing them into neat, well-organized, illustrated and expanded finished notes. Throughout classroom work, instructors are warned against presenting material in such a way that it is "transferred from the instructor's files to the student's notebook without passing through the mind of either."

Laboratory work is accomplished with small sections divided into squads of between two and four students. All the work is done by the students themselves and each student is required to take an active part in each experiment. The type of laboratory work in which highly specialized instructors demonstrate large and complicated equipment to a group of bewildered students has no place in the Thayer School system.

Sir Francis Bacon once wrote of the scientific mind that it has "no hankering after novelty and no blind admiration for antiquity." Dean Garran's administration of the School has typified this attitude. During the twelve years of his direction of the School, improvements and advances have been made in many directions. Total enrollment in the two-year curriculum increased between 1933 and 1942 from 16 to 47, and necessary additions to the faculty increased its number from three to seven. Since it is the general impression that the Thayer School is a small school, it may be of interest to note that at this time the enrollment of 15 fifth-year civil engineering students was the second largest senior civil engineering enrollment in the "Ivy League," Cornell leading with 19 and Yale being in third place with nine.

Modernization of facilities was undertaken immediately under Dean Garran's direction. Existing laboratories were improved and woodworking and metalworking equipment installed. A soil mechanics laboratory was established for instruction purposes. Thayer School was one of the first to establish such a laboratory which is now a required facility in all engineering schools. The work of modernizing the classroom and laboratory facilities in Bissell Hall prepared the School for drawing up space requirements and specifying built-in equipment in its new home constructed in 1938-3938-39- The present building is named for Horace S. Cummings '62; a bequest to the College in his memory provided funds for its construction. It represents one of the most modern and completely equipped engineering buildings in the country and is ideally adapted to the civil engineering requirements of the School.

The engineering library which is housed in the building has been completely reorganized and catalogued on the Dewey system. It contains over 12,000 items including more than 5,000 reference and textbooks and a full collection of university and society publications and pamphlets. Of particular historical interest is a collection contributed by General Thayer from his personal library. This collection consists of 600 volumes of historical and military works extending from the Memoires de Montecuculi published in 1712 to contemporary books of Thayer's time, and about an equal number of volumes on architecture and engineering dating as far back as Palladio's Architecture published in 1721.

As in Baker Library, the stacks are open to the students and the library itself is available at all times for reading, study, and browsing.

The curriculum has been subjected to constant examination and evaluation by Dean Garran and his faculty and changes have been made from time to time to meet the "needs of the times." The fundamental philosophy of the curriculum has been to provide students with a thorough instruction in the basic subjects of engineering and allied fields and to avoid the high degree of specialization which has characterized some engineering education during the past two decades.

In the summer of 1939, the five-week summer surveying course was moved to new quarters in the Haffenreffer estate in Canaan Street, New Hampshire. Unlike engineering schools located in urban communities, Thayer School had always been able to maintain a summer camp in its normal headquarters since the topography of Hanover is well suited to that type of work. However, the move to Canaan Street proved to be advantageous in permitting more effective concentration on the summer school work and in developing an esprit de corps among the students, and between students and faculty which could only be possible by living as well as working together. The new location of the summer work was therefore entirely successful and it is hoped that the property will be available for this purpose again after the war.

An experiment in civil engineering instruction which was enthusiastically received by the students was the construction of concrete abutments for a bridge across Mink Brook in Etna in the spring of 1943. Under the direction of Professor John Minnich '29, a group of senior civil engineering students worked full time during a week's vacation and half time during the brief "intersession" term of that spring. The work involved moving the existing highway bridge to a temporary location, removing the old masonry abutments, constructing new concrete abutments, and placing the super-structure on the new abutments. The results were entirely satisfactory to the Town of Hanover, and provided the students with an educational experience which they will not soon forget.

In the fall of 1937, President Hopkins wrote to Dean Garran, in connection with plans for the new Thayer School building to be located on Tuck Mall, "In considering the future of the Thayer School, I become more and more convinced that there would be advantage to the School in a closer relationship with the Tuck School by which possibly in the course of time there might be more joint courses available to both schools." This thought turned the attention of the Schools to the possibility of a combined engineering and business administration curriculum, and in the fall of 1940 the first Tuck-Thayer class matriculated. Owing to the interruption of the war and the fact that the facilities of both schools have been devoted almost entirely to the civil engineering and supply corps programs of the Navy, respectively, only two classes were able to complete the new combined engineering and business administration curriculum. With the return of normal educational processes, however, it is expected that the Tuck-Thayer curriculum will be resumed since it has aroused widespread interest both among students and within industry.

The philosophy of this curriculum is that in a wide variety of fields the principles of both engineering and business administration are applied. It is believed possible to prepare qualified students for eventual administrative work in these fields by offering them a solid foundation in the basic subjects of both engineering and business administration. A coordinated selection of elective studies superimposed on the basic subjects will enable the student to concentrate part of his second- year work toward a specific field or line of activity in which he is most interested or for which he seems best adapted. Never- theless, should he actually engage after graduation in a different field, as often happens, his education will have given him the fundamentals since he will have been required to include the basic business and engineering subjects in his curriculum. Thus, here as in the Thayer School and Tuck School curricula, specialization which would result in limiting the scope of a graduate's activities is carefully avoided.

Feeling that the School should take an active part in the College as well as in the community, Dean Garran has given freely of his own time and has made available the facilities of the School and the services of the faculty .members in the interests of national defense and the war effort during the past four years. In the fall of 1940, he initiated the Civilian Pilot Training Program for Dartmouth College students. Ground School was conducted in the Thayer School building and the students received their flying instruction at the White River airport. In the two years through which the program was continued one hundred students completed the primary training and one class of ten students completed the secondary training. The College was complimented on this program by the Civil Aeronautics Administration which considered it one of the best planned and executed programs in the country.

In the summer of 1941, engineering schools throughout the country were urged to establish training courses under the federal Engineering Defense Training Program. The purposes of these tuition-free courses were the upgrading of men and women in industry and the preparation of others not already engaged in industry. Five courses were organized under Dean Garran's direction and carried on through the summer by members of the Thayer School and College faculties. The program was continued and broadened under the Engineering, Science, Management War Training auspices until the spring of 1944 when Thayer School requested that direcdon of the work for this area be turned over to the University of New Hampshire and Norwich University. During the three- year period, 45 separate courses had been given to a total enrollment of 1318 men and women in Hanover and neighboring towns within a radius of forty miles. Members of the Thayer School, Tuck School, and College faculties were active in the program.

The first public announcement that Dartmouth College was approved for the Navy College Training Program appeared in metropolitan newspapers in the winter of 1943 indicating that Dartmouth was approved for engineering. Since July, 1943, the School has concentrated its efforts on two programs, the full eight-term curriculum for civil engineer candidates, CEC(S); and serving the College with instruction for deck officer candidates in required courses in elementary electrical engineering and elementary heat power. Enrolled in the civil engineer curriculum during the present term are eight seventhterm trainees, 29 fifth-term trainees, representing the most advanced group to have received their full college training in the V-12 program, and 46 third termers.

In preparation for courses to be taught to large numbers of deck officer candidates taking third-term and fourth-term work in the College, the facilities of the electrical laboratory were increased, new equipment was installed in the testing and hydraulic laboratories for tests of various types of internal combustion engines and, with the cooperation of Mr. W. H. Moore and his staff, equipment was arranged in the College heating plant for steam turbine tests. In order to handle the classroom and laboratory instruction for as many as 400 trainees in these courses, the Thayer School faculty was increased to eleven members.

With characteristic foresight, Dean Garran, with representatives of the departments involved, has drawn up complete and detailed plans for post-war activities of the School. Of primary importance in this program is the establishment of curricula in mechanical and electrical engineering in addition to the continuation of the civil engineering curriculum and the resumption of the combined engineering and business administration major. At the time the School was founded, the term "civil," included in its name, differentiated it from military engineering. Since then, the term has acquired a more restrictive meaning, and accordingly the name of the School was changed in the summer of 1941 to Thayer School of Engineering. The adoption of the new curricula will enable the School to cover three of the four principal fields of engineering without involving the narrow specialization which is reflected by the eighty different engineering curricula to be found in engineering school catalogs in this country.

One of the outstanding features of the proposed curricula in civil, mechanical, and electrical engineering is that the first semester work is common to all curricula and a minimum of concentration in the major study is included in the second semester work. Thus, it will be possible for students to postpone their selection of a major study until after they have had an introduction to each field of engineering in the first semester, and if at the end of the second semester they should decide that their choice was unwise, they may fit into second-year work in a different curriculum by taking summer school instruction in that field.

In recognition of engineering as a learned profession, the work of the twoyear curriculum is not limited to technical subjects. In all three engineering curricula there are four required semester courses in non-technical subjects. The material presented in these courses is suggested by their titles: Accounting, Engineering Economics, Engineering Law, and Professional Re: lations of the Engineer.

The proposed mechanical and electrical engineering curricula have been developed after consultation with other engineering schools which have offered these curricula in the past and adapted to the philosophy which has characterized Thayer School policy since its founding. Believing that the combined engineering and business administration curriculum should follow a broader philosophy than any represented by the industrial engineering approach of other institutions, Dean Garran and Dean Olsen recommended that a study be conducted of the needs and opportunities in various industries for men with an educational background in both fields. This study is now in progress and will form the basis for the post-war Tuck- Thayer curriculum which, it is believed, will be unique in the field of education.

The expansion of the Thayer School curriculum to include mechanical and electrical engineering necessitates a corresponding development of the physical facilities of the School which are at pres- ent primarily adapted to civil engineering. Space and arrangement requirements have been worked out and form the basis of the architect's studies shown on the next page which recommend the addition of two wings to the present Cummings Memorial Hall, one wing to house electrical and the other mechanical engineering. The Tuck- Thayer curriculum will be serviced by both of these hew departments as well as by the existing facilities of the Thayer School and Tuck School.

In fitting summary of the present status of the Thayer School, President Hopkins said last month,

In the long and distinguished history of the Thayer School I do not think that things related to the School have ever been in better condition than at the present day. Whether in the administrative direction of the School or in its organization, the auspices are altogether favorable. Blessed with a capable and a cooperative faculty, with more adequate quarters than ever before and with more ample facilities, the School faces the overwhelming demands of the future under conditions as favorable as could be wished for it except for its lack of endowment. It seems to me that the faith of those who have conceived and developed its policies and of those who have undergone its discipline and from their positions of importance in the outside world have supported it with their confidence is being abundantly justified.

SYLVANUS THAYER, 1807, founder of Dartmouth's Thayer School, is honored at West Point with this statue of the "Father of the Military Academy."

THREE SUCCESSIVE HOMES of the Thayer School, left to right, are the present Thayer Lodge, which the School occupied from 1893 to 1912; Bissell Hall, former gym, which served as engineering headquarters from 1912 to 1939; and the Horace S. Cummings Memorial, modernly equipped home of the school today.

ROBERT FLETCHER, first director of Thayer School, who during his 47 years of leadership laid the solid foundations for today's growth.

THE THAYER SCHOOL FACULTY, slightly enlarged today by College teachers helping with Navy courses, is shown assembled in the club-like school library. They are, left to right, front row: Joseph J. Ermenc, Edward S. Brown Jr. '34, Dean Frank W. Garran, Assistant Dean William P. Kimball 28 who wrote this article, and John H. Minnich '28. Back row: Nathan H. Rich, Francis R. Drury '27, James P. Poole, Norman E. Wilson, Rexford Moulton, S. Russell Stearns '37, and John M. Hirst '38.

PRACTICAL CIVIL ENGINEERING LESSONS were learned by Thayer School students in 1943 when they constructed concrete abutments for a bridge across Mink Brook in Etna. The experiment was a huge success, giving the men experience they will vividly remember through many engineering days to come.

LABORATORY WORK at Thayer School is aided by excellent modern equipment. Here, Navy V-12 men in a heat power course are conducting diesel engine tests as part of their thorough training.

THAYER SCHOOL SURVEYORS shown in contrasting poses of the 19th 20th centuries, the latter taken recently on snow-blanketed Tuck Mall. Assistant Dean William p. Kimball, Professor of Civil Engineering and author of this article, looks on with a mentor's eye in the picture at the right.

OVERSEERS OF THE THAYER SCHOOL, consisting of the President of the College and four others, include, left to right, Luther S. Oakes '99, president of Winston Brothers Co., Minneapolis; Charles F. Goodrich '05 (D. Eng. '39), chief engineer, American? Bridge Cos., Ambridge, Pa.; and Frank E. Cudworth '01, office engineer, Walsh-Kaiser Corporation shipyard. Providence, R. I. The vacancy on the Board caused by the death of Charles R. Main '07 has not yet been filled. Two of the Board members are elected from nominations by the Thayer Society of Engineers, giving alumni of the School representation in the management of its affairs.

PLANS FOR EXPANSION of Thayer School's present building are shown in these architect's drawings of the front (above) and rear views of the Cummings Memorial when proposed wings have been added to accommodate enlarged work in mechanical and electrical engineering. J. Fredrick Larsen is the architect.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA CIVIL WAR STUDENT

February 1945 By EDWARD CHASE KIRKLAND '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Casualties

February 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1945 By JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

February 1945 By H. F. W.

Article

-

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB CREDITED WITH 51 MILES OF TRAILS IN 1920

February 1921 -

Article

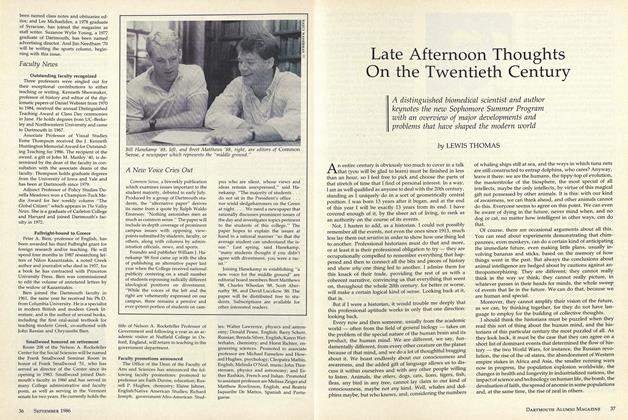

ArticleFaculty News

September 1986 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

May 1948 By H. L. Duncpmbe, JR. -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1955 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleSpecial Training Courses

April 1942 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleTreasurer

April 1942 By The Editor