FRANK MUNSEY PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, BOWDOIN COLLEGE

IN the literature about businessmen there is something for every taste and age. The children can cut their teeth on the works of Horatio Alger and learn how industry, perseverance, honesty, and luck will surely lead to business fortune. Probably very few adults, except for nostalgia or scholarship, will reread any part of this literature. For them Irvin G. Wyllie in The Self-Made Man in America; TheMyth of Rags to Riches has analyzed the genre. Though Mr. Wyllie fails to extract all the humor inherent in his material or to inform us how much myth corresponds to fact, he at least demonstrates by implication that Norman Vincent Peale is not a modern invention.

Also in the realm of fiction are the business novels. Though they have been brought up to date by a formula which includes military service abroad and a little extracurricular sex, they have not surpassed two of the best, Sinclair Lewis's Dodsworth and J. P. Marquand's Point ofNo Return, in their picture of the motives, tensions, loyalties, and functioning of the world of business.

At a somewhat different level are the business biographies. I did not believe it was any longer possible to write about our historical business characters in the manner of the "muckrakers" of the early twentieth century, but W. A. Swanberg in his Jim Fisk; The Career of an Improbable Rascal has recently done so. Fisk was a fumbling voluptuary, a physical coward, and a picturesque wrecker of railroads. No doubt Swanberg thinks of himself as very modern, as so sophisticated that he can play Fisk for laughs or "kicks" and not for censure. It is at least arguable that in the absence of radio and television Americans contemporary with Fisk esteemed him for his entertainment values. For all the raised trumpets of the publicity boys, this is an old-fashioned book.

Actually, a more fundamental revaluation of the businessman has been long underway in biographical writing. For Commodore Vanderbilt, a contemporary and competitor of Fisk, there has been an informative biography since 1942, when Wheaton J. Lane wrote Commodore Vanderbilt; An Epic of the Steam Age. Vanderbilt, although he resembled Fisk in his vanity and craving for the spectacular, was courageous and a shrewd business builder. Talent of this order seldom passes to another generation, but Wayne Andrews in The Vanderbilt Legend; TheStory of the Vanderbilt Family, 1794-1940 demonstrates that the Commodore's son was a great railroad man. The book is also fascinating for its forays into social history. It surveys the parade of the Vanderbilt palaces, "cottages," and "villas"; and those who have visited "Biltmore," near Asheville, North Carolina, or "The Breakers," at Newport, will be grateful for this background, as well as for the delightful irony - the perfect tone in this instance - with which Mr. Andrews has written about the Vanderbilts and their housing.

In general it is wise to suspect a biographer with a mission. This warning should not apply to Allan Nevins, who has dedicated himself to overturning the conceptions about businessmen inherited from the era of Roosevelt and Wilson. Of the genuine giants, Nevins tackled John D. Rockefeller in the thirties; and when new material was unearthed, he did the job over again in the fifties. His Study inPower: John D. Rockefeller, Industrialistand Philanthropist is a far cry from Ida M. Tarbell's History of the Standard OilCompany, commissioned early in the century by that entrepreneur of "exposure," S. S. McClure. Perhaps the only similarity between the two works is that both are in two volumes. The title of Nevins' work is a key to its superior breadth and insight. There is as much about the University of Chicago and the Rockefeller Institute as about railroad rebating.

Nevins has also treated in two volumes the enigmatic Ford. This is a history of the automobile industry and of Ford's irreconcilable diversity of interests from anti-semitism to square dancing. In my estimation it is not so successful a biography as that of Rockefeller, but it may be more interesting, because Ford's decisions touched the lives of millions more obviously than did Rockefeller's. The big motor-makers now so stubbornly resisting the small car might learn lessons from Ford's business disaster in refusing to shift from the Model T. Even then, Model A for all its stylistic conformities was too little and too late. Fathers bent upon shaping their sons to a business pattern can also learn a prudential lesson from Ford's unfeeling methods of bringing up a business heir.

Most people are so in the habit of personalizing what happens that conceivably a series of business biographies is the best method to effect a revolution in popular attitudes toward business. One trouble is that men become legends so quickly. Already Ford and Rockefeller are in the shadows with Fisk and Vanderbilt. ("If you hear it, it's news; if you read it, it's history.") Besides, the personal approach is bound to have about it something too distinctive, perchance even eccentric. "Philanthropist" and "robber baron" worked within a system deriving its features from the many as well as the few, from those outside of business as well as those in it.

Since this review article began with the cradle, perhaps it should end with the grave. Sigmund Diamond in The Reputation of the American Businessman describes the popular and journalistic reaction to the deaths of six business titans. Few would forecast that an analysis of massed obituaries could be either revealing or interesting, yet this book is both. On the whole, it concludes that Americans once believed business success was due to the superior qualities of individual businessmen; now they ascribe it to the virtues of the American system. This volume is an important step toward understanding both a business system and Americans.

Edward Chase Kirkland '16, whose home is close to Hanover in Thetford Center, Vt., has been Professor of History at Bowdoin since 1930. Past president of the Economic History Association and of the Association of University Professors, he is one of the nation's leading historians and holds honorary degrees from Dartmouth and Princeton.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

May 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

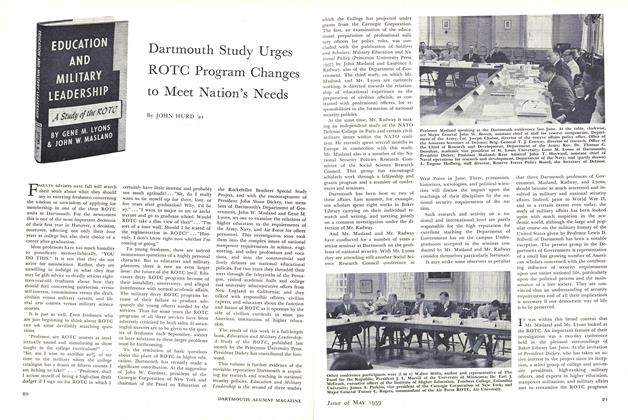

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

May 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

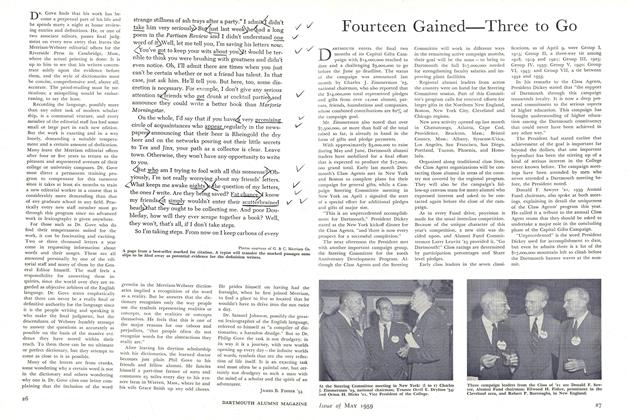

FeatureFourteen Gained — Three to Go

May 1959 -

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

May 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1959 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, JAMES LeR. LAFFERTY

EDWARD CHASE KIRKLAND '16

Article

-

Article

ArticleD.O.C. House Dedication

MARCH 1929 -

Article

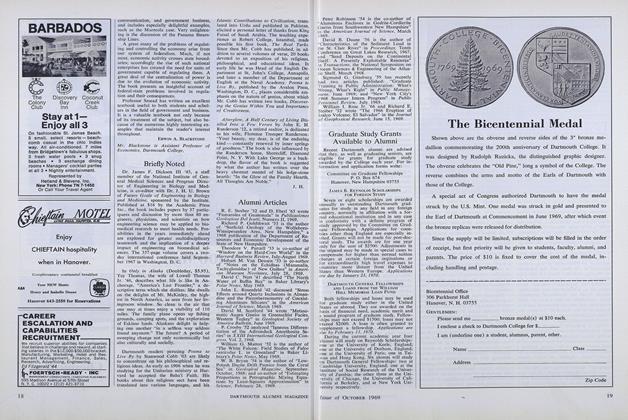

ArticleGraduate Study Grants Available to Alumni

OCTOBER 1969 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth-Wellesley

OCTOBER 1970 -

Article

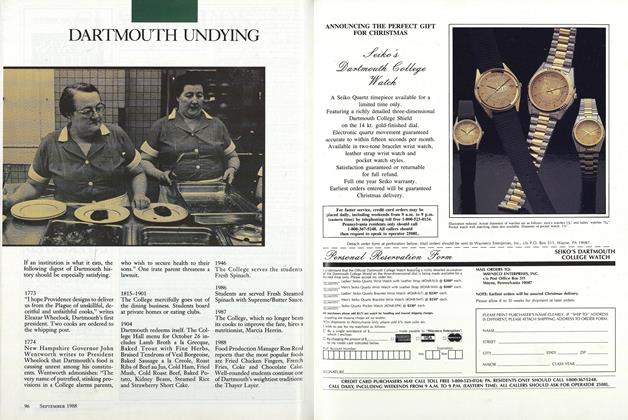

ArticleDARTMOUTH UNDYING

SEPTEMBER 1988 -

Article

ArticleFreedman's Seven Biggest Decisions

February 1992 -

Article

ArticleFour-Diamond Trail Food

NOVEMBER 1998 By Kevin Goldman '99