Dos POU STO," boasted Archimedes on discovering the principle of the lever, "kai ton kosmon kineso." Which is, being interpreted, "Give me a place to stand and I will move the universe." Scientists usually ascribe the chief place in point of utility to the invention of the wheel, but the lever follows fast. And what is a lever without a fulcrum—and a pou sto?

One who scans the history of Dartmouth College may underestimate the part which the education of Indians played in calling the College into being. Few of the "redmen" appear to have been educated at any time, and the number at the present day is smaller still. Nevertheless it was the idea of evangelizing the aborigines that so fascinated the original sponsors of the College that they gave of their substance to enable its creation. If missionary zeal had been less warm, and if Samson Occum had not been available as a sort of Exhibit A to the earnest populace of Great Britain what Dr. Wheelock was doing for the denizens of the Wilderness, there might never have been a Dartmouth.

The Indians faded early from the picture, and with their loss of status as the primary raison d'etre came a rapid diminution of British interest. But the work had been done. The new college was a fait accompli. Lord Dartmouth, in recognition of an expenditure which in modern times might not seem especially notable, had given his name to an institution of learning. Apparently the modesty of Governor Wentworth alone prevented the naming of the college in his own honor and diverted that distinction to the British peer who, in private life, had been honest William Legge.

It is possibly in order, after 175 years of corporate life, to remind the reader of the important part played by the Indians in this matter as the fulcrum—the "pou sto" for Wheelock's lever. Not for nothing has an Indian war-cry become the official college cheer. A college designed for the better education of white boys in New Hampshire might, and probably would, have lacked the romantic incentive which gave to the expedition of Whitaker and Occum the measure of success which they achieved.

They were quite sincere about it, of course. The original idea was, as one might say, aboriginal. To educate and evangelize the Indians really was the primal aim, and it ceased to be only because circumstances operated to change the plan as a matter of practical development. But the Indian aspect of the case was what really captured the imaginations of the day and translated those enthusiasms into pounds, shillings and pence. It was the "pou sto," the locus standi, the essential ingredient which activated interest in England, where the money was—money without which the new college could not have been founded. So the Indian connotations of our College name merit a bit of attention as we square away for our two hundredth anniversary. The Indians' need, and the zeal to serve that need, called Dartmouth College into being.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE THAYER SCHOOL

February 1945 By PROF. WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28, -

Article

ArticleA CIVIL WAR STUDENT

February 1945 By EDWARD CHASE KIRKLAND '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Casualties

February 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1945 By JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI, WILLIAM T. MAECK

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth as Unusual

November 1942 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleEducation for the Submerged

December 1942 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleIntercollegiate Interim

January 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWho Calls the Tune?

April 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleMilitary Training

November 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleQuestion of Timing

April 1945 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

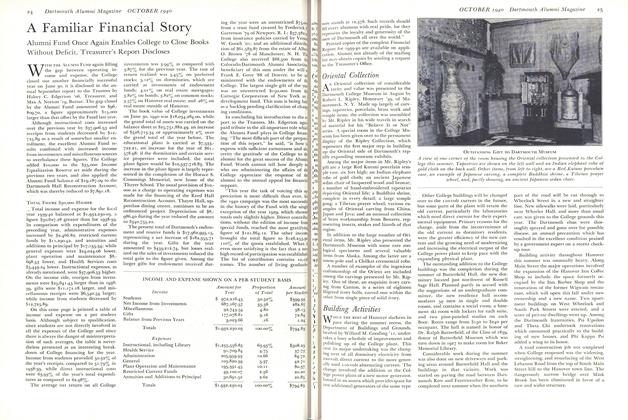

ArticleA Familiar Financial Story

October 1940 -

Article

ArticleSummer Course for Writers

August 1942 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth 15, Penn 0

November 1960 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleLACROSSE

JUNE 1964 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

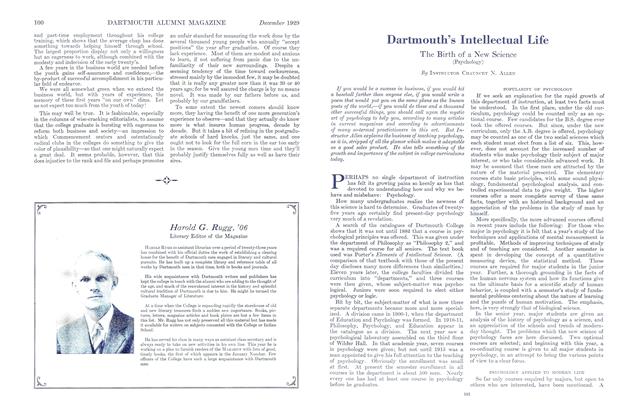

ArticlePOPULARITY OF PSYCHOLOGY

DECEMBER 1929 By Instructor Chauncey N. Allen -

Article

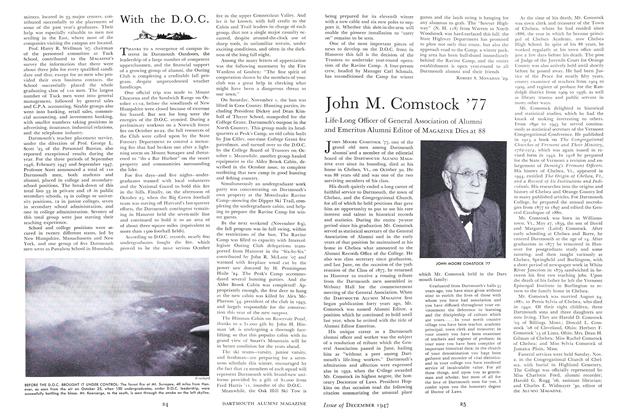

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

December 1947 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29.