1815-1860, by Arthur Alphonse Ekirch, Jr.'37. Columbia University Press, 1944, 305pp., $3.50.

Americans have been enthusiastic believers in the idea of progress. Nothing can stand in the way of the upward and onward surge of American civilization. The rapidly increasing size and wealth of the United States can be credited to the intelligence of our people and the excellence of our form of government. Only a few soured souls talked of unusual natural resources, while an even smaller number of cynics doubted whether more railroads and more prohibition societies necessarily indicated a development of the American mind and spirit.

American optimism in our early history led us to expect that other nations would copy our institutions. When this hope was partially disappointed we expanded so that the national boundaries included an ever and ever large portion of the world. The American idea of progress was at once the cause and the result of American expansion. Dr. Ekirch has described the American idea of progress as it was expressed during the early nineteenth century. His 257 pages of text crammed with names and quotations, and buttressed by impressive footnotes and a breath-taking bibliography, are all that a Ph. D. thesis should be, even when it has been written under that able and diligent master of research, Prof. Merle Curti. The general thesis is made abundantly evident, even though a considerable number of the social and religious reform movements of the time are barely mentioned, if at all. If any one has believed that Americans of the early nineteenth century did not believe in progress, his conviction is now clearly untenable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

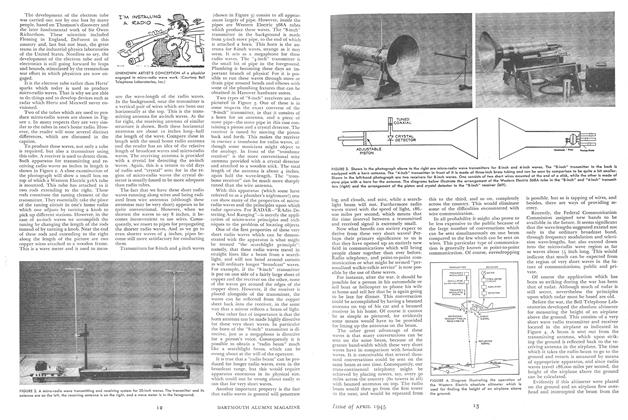

ArticleRADIO WAVES AND RADAR

April 1945 By GORDON FERRIE HULL JR. '33, -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

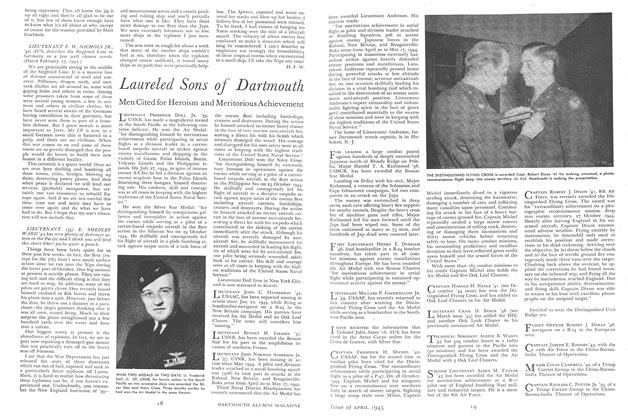

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

April 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1945

Robert E. Riegel.

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

June 1935 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

February 1939 -

Books

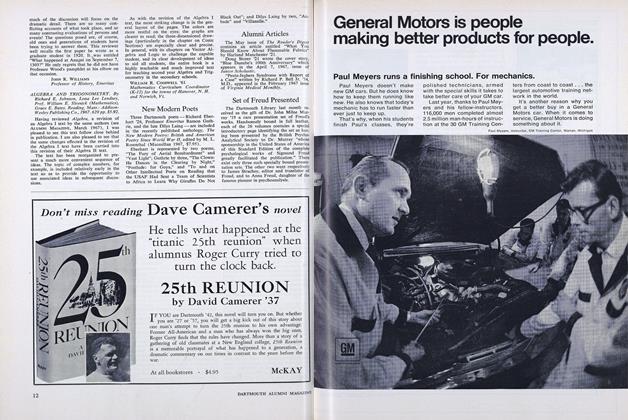

BooksSet of Freud Presented

JUNE 1967 -

Books

BooksFINDING THE NEW WORLD

December 1935 By Harry B. Preston '05 -

Books

BooksCONTEMPORARY ECONOMIC SYS.

October 1940 By John G. Gazlen -

Books

BooksMUSIC AND THE MUSICIAN IN JEANCHRISTOPHE, THE HARMONY OF CONTRASTS.

MAY 1969 By LUCIEN DEAN PEARSON