Notes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief.

March 1979 R. H. R.Notes on lost causes and an enlistment against Nature, as brave as it was brief. R. H. R. March 1979

In 1910, William James, the Harvard psychologist-philosopher, first suggested the concept of universal work service for the young. "The moral equivalent of war," James called it. If, he wrote, "there were instead of military conscription, a conscription of the whole youthful population to form for a certain number of years a part of the army enlisted against Nature, the injustices [of purely military conscription] would tend to be evened out, and numerous other goods to the commonwealth would follow."

Forty years later, in Sharon and Tunbridge, Vermont, James's idea was put briefly to the test. For a scant 12 months in 1940-41, a group of young Dartmouth and Harvard men, recent graduates and undergraduates, initiated Camp William James to discover whether the theoretical concept of "the moral equivalent of war" was translatable into hard, practical work on Vermont farms.

Fortunately, the camp had its historian, Jack J. Preiss '4O, himself a member of the founding group. His manuscript, originally written in 1950, lay dormant until 1978, and now, almost four decades after the event, Preiss's CampWilliam James (Norwich, Vermont, Argo Books. Softbound. 256 pp. $7.00) tells a historically significant story but a story, too, with some clear and present analogues.

The theoretician of the social experiment was the late Professor Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy. A German by birth and social philosopher by training, Rosenstock-Huessy was no stranger to the concept of work service. He played a leading role in founding German work camps during the brief period of the Weimar Republic following World War I. As the power of Nazism grew ever more pervasive, however, it became increasingly clear that the democratic work-camp movement in Germany would inevitably be perverted to more sinister purposes, and so Rosenstock-Huessy and his family emigrated to the United States, where, after teaching briefly at Harvard, he joined the Dartmouth faculty.

Rosenstock-Huessy was also the chief catalyst of the Camp William James experiment. It was he who, in the summer of 1940, brought together two groups, recent graduates of Harvard and of Dartmouth, who were working for similar social goals though by dissimilar means. The Harvard group had joined the Civilian Conservation Corps in an attempt, by working from within, to transform it from a make-work haven for poor and unemployed young men to something more nearly approximating William James's ideal "army enlisted against Nature." The Dartmouth group, all of the Class of 1940 — Robert O'Brien, Arthur Root, Louis Schlivek, Alfred Eiseman, and Jack Preiss — had taken the more practical approach of hiring themselves out as summer labor on Vermont farms. Almost by chance they ended up working in and around Tunbridge.

Meeting frequently at Rosenstock-Huessy's house in Norwich and drawing heavily upon his experience and leadership, the young men slowly hammered out their ideas. They would petition the government to reopen a recently closed CCC side-camp at Sharon, Vermont, as a pilot program to train the leaders who in turn, it was envisioned, would begin to transform the CCC into a permanent organ of national service. The Sharon camp would differ significantly from the typical CCC camp. It would enroll not just the poor, the undereducated, the unemployed, but young men from all walks of life; instead of working solely on federally controlled projects in state and national forests, the Sharon group would be "a labor force to work in the towns surrounding it — on the roads, maintaining schools, on farms, on all needed community projects"; and instead of being assigned and directed from Washington, the work would be directed by the local communities themselves.

Enlisting the help of such prestigious supporters as Dorothy Canfleld Fisher, Dorothy Thompson, and Eleanor Roosevelt, the young men showed themselves remarkably adept both at manipulating the levers of political power in the federal bureaucracy and in organizing eight Vermont towns — Chelsea, South Royalton, South Strafford, Sharon, Randolph, Bethel, Hartford, and Tunbridge — into a more or less cohesive legal entity to sort out priorities on the local work projects. After a particularly persuasive plea from Dorothy Thompson, President Roosevelt ordered the experiment funded in October 1940. In mid-December, with William James's two sons in attendance, Camp William James was formally dedicated.

It never really got started. Though regular CCC enrollees began to transfer into the Sharon camp to join the college men, outside events foretold the end even before the beginning. In September of 1940, three months before the camp's proud dedication, the Selective Service Act had been passed. Clearly, the nation's efforts were being increasingly channeled toward real war, not its "moral equivalent." Moreover, Camp William James began to get a bad press. It was attacked with particular vehemence by anti-New Deal politicians, among them Rep. Albert J. Engel of Michigan, who began Congressional hearings on the "German aspect" of the camp and suggested publicly that "the Sharon Camp was the first part of a plan to institute Nazi-type work camps in this country, and that the presence of 'over-privileged' youth in the Camp was to train them to be Hitlerite leaders." Nor was it overlooked that Rosenstock-Huessy was not an American citizen. All of this, of course, made good headlines.

Even among its friends support for the camp eroded. To be sure, several prominent persons of good will came to the defense: Senator Aiken, Senator Flanders, Dorothy Thompson. Many Dartmouth undergraduates even volunteered their services, though the College chose to stay officially aloof from a now controversial and highly politicized issue. What help there was came too late. On February 17, 1941, the CCC withdrew its support, which meant in effect that the Sharon camp must close.

Still the idea persisted. Undeterred, though with something of a lost-cause psychology about them the Tunbridge Group, as they called themselves, went private. Having procured enough money for survival from private foundations and individual donors, the group bought a farm in Tunbridge and, with the coming of soring, started over.

But things were not quite the same. Though labor cadres were supplied to help local farmers and to work on locally directed projects, particularly resettlement of abandoned farms, now the camp was also required to make at least part of its own way financially. Accordingly, they turned to the time-honored Vermont practice of maple sugaring in March, and by late spring had acquired a tractor for large-scale gardening.

In summertime the living was easy. What the camp may have lacked in direction it made up for in activity. Intensive recruiting campaigns on campuses near and far brought many new members to Tunbridge. From Dartmouth alone, in addition to the five founding members, at least seven more graduates and undergraduates joined Camp William James during 1940-41: William Uptegrove '42, Arnold Childs '39, Roy Chamberlin '38, Page Smith '40, Clint Gardner '44, Russell Hurlburt '44, and Charles Dell '42. Mrs. Roosevelt visited the camp and devoted one of her "My Day" columns to its activities. Stuart Chase and Meyer Berger wrote sympathetic pieces for the national press. Satellite camps in Mexico and Alaska were even contemplated.

With the coming of fall, however, the summer soldiers began to melt away. The continuity of membership was irreparably broken; the draft and voluntary enlistment in the armed services had taken their toll. More important, though the external forms — some of them — remained, the informing spirit was dissipated; the remaining founders discovered themselves more members of a rural commune than of James's "army enrolled against Nature." Willy nilly, events in faraway Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, effectively put an end to Camp William James in Tunbridge, Vermont.

What did it all accomplish? In terms of concrete, tangible achievements, not much; in terms of future influence, a great deal. It was indubitably a first. Sargent Shriver, first director of the Peace Corps, has acknowledged in print how profoundly the inception of the corps was indebted to the earlier experiment conducted in rural Vermont. And today, as Page Smith points out in his introduction to Preiss's book, when Congress "considers proposals to reestablish, along new lines, a corps of young people volunteering for national environmental service, it is instructive to note that many of the issues as to the proper role, recruitment, and organization of an 'ecology army' were first confronted and debated by the founders of Camp William James." There could hardly be a more appropriate time than our own, Smith concludes, "to retrieve the history of Camp William James, the first practical effort to give effect to the idea of national service in time of peace."

In terms of its own time the late Bill Cunningham '19 had it about right: "College Idealists Face Losing Battle," read the headline of an article he wrote on the camp for the Boston Herald in 1941. But the longer perspective of history has altered that conclusion. The story of Camp William James is a paradoxical story of success in failure.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

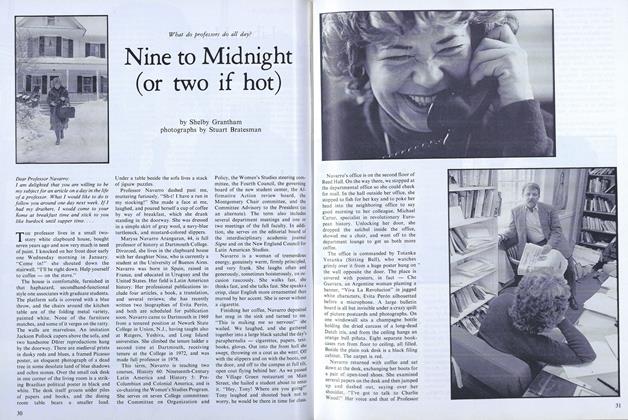

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

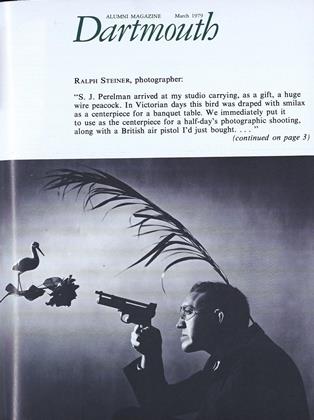

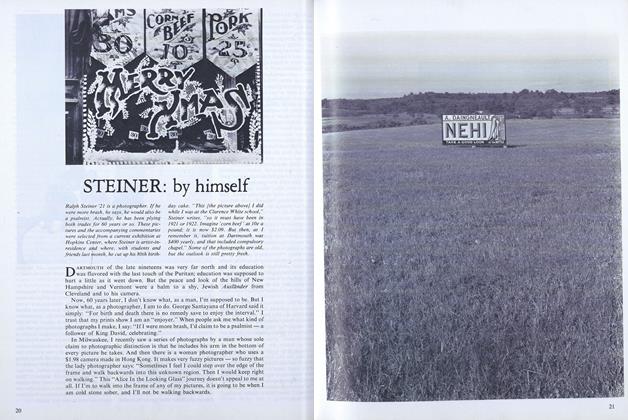

FeatureSTEINER: by himself

March 1979 -

Article

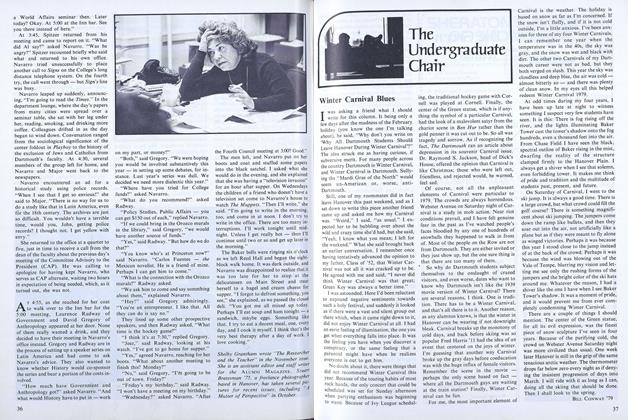

ArticleWinter Carnival Blues

March 1979 By Biĺ Conway '79 -

Article

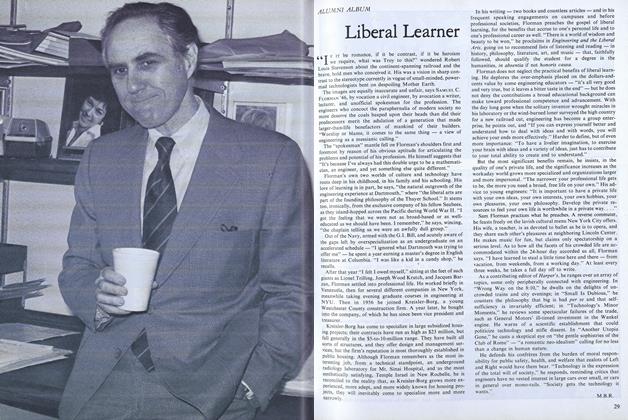

ArticleLiberal Learner

March 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1979 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1979 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR.

R. H. R.

-

Article

ArticleNotes on a Distinguished Defendant and the Supreme Court’s Great non-decision

DEC. 1977 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksLooking Back

April 1979 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksWhat If?

June 1981 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksAt-Variances

OCTOBER 1981 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksNot for Art's Sake

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMan in the Cambric Mask

JUNE 1982 By R. H. R.

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

January 1917 -

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

November 1945 -

Books

BooksRights and Wrongs

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Charles M. Culver, M.D. -

Books

BooksTHE HAPPY END

June 1939 By H. G. R. -

Books

BooksGEOCHEMISTRY OF BERYLLIUM AND GENETIC TYPES OF BERYLLIUM DEPOSITS.

OCTOBER 1966 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksSIR RICHARD STEELE

December 1934 By William A Eddy