PUBLICATION CENTENNIAL REACHED BY ALUMNUS' FIFTY-EDITION BOOK

i, Professor of Botany

THE YEAR 1870 was not only the birth year of the Dartmouth Scientific Association but also the 25th Anniversary of an event closely associated with the scientific interests of Dartmouth. The year 1945 is therefore the Centennial of that scientific event—the publication of the first edition of Wood's Class-Book of Botany at Claremont, N. H. Before the end of its usefulness, this famous textbook and manual had gone into its 50th edition and been sold to over a hundred thousand students.

Dartmouth has a double claim for recognition of its contribution to the development of this book—the first botany text to be approved by the American public. In the first place, the author was a Dartmouth graduate and, secondly, he collected the materials for the book in the vicinity of Hanover and with the active assistance of a member of the Dartmouth faculty.

Alphonso Wood was graduated from Dartmouth in 1834, with Phi Beta Kappa rank. He had been born in Chesterfield, N. H., in 1810, educated in the schools and academy there and, like many students of his time, had taught in the rural schools throughout his college course. At Dartmouth there had been no formal training in science but he had learned something about plants through contacts with lecturers and students in the Medical School, where biology was recognized as an important science.

After graduation he became a teacher of Latin and Natural History at Kimball Union Academy, only thirteen miles from Hanover. There he found his greatest interest to be in plants and the teaching of botany to the coeducational student body. Following his marriage in 1842, his wife encouraged this special interest and he gave ever greater attention to the subject with emphasis on field botany and the study of living plants.

In the same year. Dr. Edward E. Phelps of Windsor, Vt., became lecturer in the Dartmouth Medical School, driving back and forth, sometimes by way of Meriden. This famous doctor and teacher taught the Materia Medica, had done special work in botany and had collected his own herbarium. Just how much he helped the teacher at Meriden, we do not know but Wood put Dr. Phelps first in the preface acknowledgments of his new Class-Bookof Botany.

This book was remarkable for its origin as well as for its immediate success in competition with other texts. It was written because Wood the obscure teacher was dissatisfied with all books prepared by professional botanists. The most eminent of these authors was Asa Gray of Harvard, Fisher Professor of Natural History although born in the same year as Alphonso Wood, then only thirty-four years old. Gray's Botanical Text-Book of over 500 pages and a thousand wood engravings was written by America's greatest botanist, then and still. In 1842 it was in its second edition, designed for "colleges, schools and private students" and published by the powerful house of Wiley and Putnam.

Early in 1844, Wood went to Cambridge and asked Professor Gray to prepare a botany text that could be used to better advantage in the many schools like Kimball Union Academy. Gray replied rather curtly that there was no need for such a book—that the academy teacher should be able to use the books on the market. After trying again to get along with them in the spring of 1844, Wood approached Dr. Gray a second time and tried to state his objections to current texts in botany. As the result of treatment which he considered rude, Wood announced to Gray "Well, if you will not, I will." Thus started the forty-year struggle for the textbook market, won easily by Wood in spite of the vigorous opposition of all the prominent botanists of the time; they sided with Gray in regarding Wood as a rank, impossible amateur, a trespasser in their field and therefore a usurper without rights.

The new book was printed privately m the following year, a well-bound, full-size, illustrated text of 475 pages but in an edition of only 1500 copies. It was sold out immediately and a second edition of 3,000 copies was at once produced through a Boston publishing house. It displaced older books on its merits alone, since the author remained at Meriden, improving the text, correcting errors and adding to the manual part of the book, since the descriptions of native plants formed the core of it and made it unique and attractive to teachers.

For this first edition, three-fourths of the species, and later more, were described from specimens, many collected near Meriden, some from the herbarium of one Abel Storrs of Lebanon, N. H., and others from Dr. Phelps' collection at Windsor. Later Wood traveled extensively to learn plants in other states, even as far as the Pacific Coast. On one such trip in August, 1866, he and Rev. G. H. Atkinson, Dartmouth 1843, climbed Mt. Hood in Oregon, the first white men to reach its summit.

From the teacher's viewpoint, he sought to have his book appeal to the reason of the student, rather than to his powers of memory. It's still a good idea. The following paragraph from the first edition's preface indicates other ideals:

"That there is need of a new Class-Book of Botany, prepared on the basis of the present advanced state of the science, and, at the same time, adapted to the circumstances of the mass of students collected in our institutions and seminaries of learning, is manifest to all who now attempt either to teach or to learn. The time has arrived when Botany should no longer be presented to the learner encumbered with the puerile misconceptions and barren facts of the old school, but as a System of Nature, raised by recent researches to the dignity and rank of a science founded upon the principles of inductive philosophy .... That theory of the floral structure which refers each organ to the principles of the leaf, long since propounded in Germany by the poet Goethe, and recently admitted by authors generally to be coincident with facts, is adopted, of course, in the present work."

For all these and other points of improvement thought to be incorporated in the new book, Wood remained modest about his project. He frequently emphasized that his book was elementary and referred the reader to Gray's books for complete details of topics. On the difficult point of correct scientific names for plants, he adopted those given by Torrey, Gray and others "for very obvious reasons." He always maintained this courteous and respectful attitude toward Gray in spite of their bitter rivalry. He was content to be a good teacher and to make good money from his various books of which about 800,000 copies were sold.

If there was any one reason for the wide sale and popularity of Wood's Class-Bookof Botany, it was the provisions he made for its use in identifying native plants by quick, easy methods. These were not found in earlier books. For this reason the new book was a great stimulus to field botany and observations of living plants. Wood's great practical contribution to the technique of rapid identification was the scheme he called analytical tables, now known as keys. In his preface, Wood gave Dr. Phelps much credit for the idea but they were first published and later improved in the Class-Book. They were both new and useful, just the tools needed by the amateur. The professionals had similar schemes based on natural affinities between families and genera but hopeless for use by others, or in the field. They still are and they are still printed in most sections of Gray's Manual, though we are promised the Wood-Phelps type of artificial keys in the next edition. It's about time after a long one hundred years.

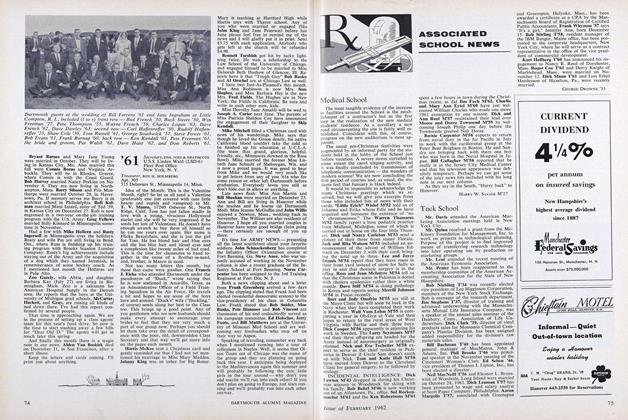

ALPHONSO WOOD 1834, teacher of Botany, whose "Class-Book of Botany" was the first textbook on the science to win popular approval in America.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT'S IN IT FOR US?

May 1945 By RICHARD E. LAUTERBACH '35 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1945 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

May 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

May 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleAMOS TUCK SCHOOL

May 1945 By HARRYR. WELLMAN '07