How WILL THE veteran rate as a student?

It is no secret in Hanover that when the war ended, Dartmouth's faculty awaited the answer to that question with some trepidation. The early rush back to school, the problem of teaching veterans was little publicized. Such matters as housing veterans, feeding veterans, crowding them into the classrooms ahead of the non-veteran students took priority in the public press. Yet even a cursory glance at the difference between the pre-war undergraduate and the new veteran suffices to explain why teachers looked forward to old jobs with a nervousness bordering on that of the young instructor facing a class for the first time. "These men are going to be mature" was the slightly querulous summary with which teachers faced the coming of the soldiers.

And they were. In the first place, the veterans were older. The average age for entering veterans last March was over 22, though it has fallen since to slightly better than 20. A high percentage of the men were married. Finally, most of them had been in the middle of the war. Would the experience of living make them scorn the experience to be gained from books? Would they be anxious only for an easy degree and a quick departure? (There were some who said that the returning soldier wanted nothing more than that after World War I.) Would their quickly found maturity make them bored with college? There were some who were afraid so.

It was nearly a year ago that Dartmouth's faculty began asking these questions. For nearly a year Dartmouth College has been largely composed of undergraduates who fought the Second World War. It is possible now to give a general answer to the question of the veteran as a student. In general, the answer is that the job of learning at Dartmouth is going very well.

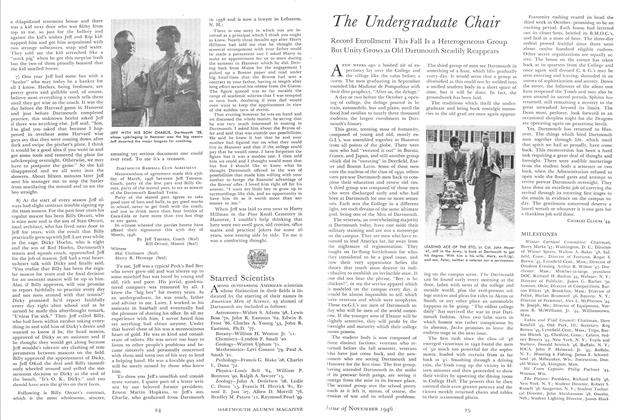

Not that there haven't been some changes since the last peacetime semester. There seems to be general agreement, for one thing, that the students work harder than students did in peacetime. There are fewer cuts. Assignments and papers are more likely to be submitted on the date they are due.

A good many of Dartmouth's teachers find a change in the classroom spirit as well: a change in the manner in which a man goes after knowledge. One veteran teacher who for years has been in the habit of posing a general problem to his

class and asking his students to answer with separate papers, put it this way: "I read off what I thought were some of the best answers, and when I had finished, the boys wanted to know what the correct answer was. I tried to explain that there was no single correct answer, but I doubt if they understood it. They simply couldn't get it through their heads that one man's answer might be good and another quite different answer might be just as good."

. The plight of the veteran in this situation is probably understandable. As soldiers, Dartmouth students were trained to believe that there was always one final answer to any problem. As students, they have to learn all over again that the answer to many a question is a temporary thing, a matter of stating the truth for the moment, knowing that it may change in the next moment. As students, they have to learn that to some questions there are many answers, or even none at all.

But what of the veterans maturity? Does he know any more than his civilian compatriot? True, he knows that college is a job which ought to be done well. He takes it seriously and plunges into it. But it is the almost untestable field of background information, the kind of knowledge which comes of peaceful years of reading widely and leisurely that the understandable gaps in the veteran's education can be shown.

Of twelve veteran sophomores and juniors in one class, eight had never heard of Sacco and Vanzetti. Five were only very vaguely aware of the name of Mr. Justice Holmes. Seven had never heard of Theodore Dreiser.

These men know how to run ships and lead platoons. They know more of life and death than do their civilian friends. But they have been busy fighting a war, and there is much they never had a chance to learn. Dartmouth's faculty, no longer nervous about what they do know, has settled down to the job of teaching them what they don't.

The Gradus section is written this month by Thomas W. Braden '40, Instructor in English and former Editor of The Dartmouth, whom we are pleased to announce as the first member of a new editorial board.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article"JEFF" TESREAU

November 1946 By EDWARD JEREMIAH '30 -

Article

ArticleADVOCATE OF PLENTY

November 1946 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleWar Story of Jiggs Donahue '15

November 1946 By James L. Farley '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

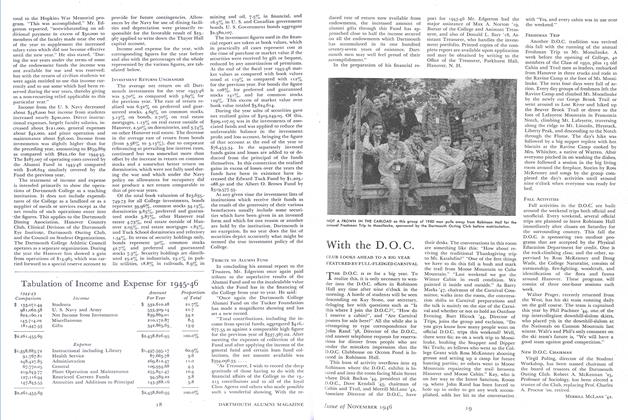

ArticleAnnual Financial Report

November 1946 -

Article

Article188 Sons of Alumni Among Entering Students This Fall

November 1946