Does Postwar Dartmouth Measure Up to Ideals and Intellectual Needs of the Returned Veteran?

March 1946 ANDREW M. SCOTT '45Does Postwar Dartmouth Measure Up to Ideals and Intellectual Needs of the Returned Veteran? ANDREW M. SCOTT '45 March 1946

OF ALL THE AGES, this is the age to be alive in. The answer to almost any question is here for the man who will seek it. It is the climax of man's development. It can be anything he makes it. The "race between education and catastrophe" is at its crucial point. If our men are small and our understanding small, we shall perish. If we can meet the challenge, the sky is the limit.

We've worked hard in our laboratories and finally come forth with a weapon that can, in fractional seconds, atomize or turn hundreds of thousands of us to charcoal. We can stage a nice home-made Armageddon any time now. And still more charming weapons are to come. We can soon look forward to mass sterilization by ray from a space ship, to atomic bombardment from space, to deadly plague loosed at will. The death ray of fiction may be just around the corner. Who can say when the first globe-circling chain reaction will take place? How long will it be till we can split our very sphere into fragments? The blockbuster, the sixteen-inch gun, the incendiary bomb were toys, kid stuff, compared to what exists in the world today.

Ten thousand times since the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima, we've been exhorted from pulpit and editorial column to acquire tolerance and the spirit of brotherly love. They tell us if we fail to acquire these, we shall pay with our lives one fine, very bright day. They are right. It is only upon Christian ideals, in the broadest sense, that peace can be based. Preaching these admirable ideals is not enough, however. We must educate. We must educate the narrow. For it is they, nice guys though they may be, who will bring catastrophe. If we would live, we must educate. Only knowledge can strip away contempt and suspicion. Only knowledge can protect us.

Our world, momently, becomes more complex. We must become broad to understand it. True, we need to specialize in order to gain employment. But that specialist training is only half of education's job. The other half is preparing men to take their places in the world as citizens. And here, specialization would be fatal. Never has there been the need for liberal education there is today. We must have wide knowledge of the things that count. It is no longer safe to lose ourselves in one subject to the exclusion of everything else. We must learn what makes individuals tick, what makes groups, institutions, and nations think and behave as they do.

We must acquire the perspective that history can give us. Imperative is a thoroughgoing knowledge of the mainsprings of politics and economics. We must learn the lessons of sociology and anthropology, of psychology and psychiatry. There are questions we must answer. How much of the information that is being unearthed about the individual's actions, reactions, defense mechanisms, and so on, can be applied to the actions of men in masses? To what extent are men as individuals and men in groups "rational"? We need to study the very process of thinking itself, learn to separate words from things, learn to recognize our own rationalizations. We need to become familiar with the new phases of medicine in order to understand the tie-up between our bodies and the way we think and act. All this is the survival minimum.

Our professors are in a position to aid us in covering this immense territory. They are supposed to have, in addition to their rounded education, mastery of one phase of learning. We can legitimately ask these men to be selective in the material they give us. We can ask that they delve into their fields and come up only with what is important. Often, however, our professors fail us. They can't see the woods for the trees. Seldom can they cut through the trivia and get at the dynamics of what they teach. They may be "learned," "erudite" men, but in a large sense they are ignorant. How few of them know their subject and can put it over in a vital, interesting way! And among these rare creatures, how more rare still is the man who can, without distortion, fit his speciality into the general scheme of things!

If a man is not stirred in his formative college years to acquire broad interests, it is likely he never will be. We can't say that much of this broadening will come to him later. It doesn't work that way. As proof I offer you the faculty. They have greater opportunities than most men, but how many take advantage of them? They have never been trained or stimulated to vary their intellectual diet. They can't give us the curiosity they themselves lack. We are in danger of becoming, like our professors, men possessed of but one part of a jigsaw puzzle. We shall be like the blind men led to an elephant. The first of these, encoun- tering a leg, said, "Why, this 'elephant' is very like a tree!" A second, feeling the trunk, declared it to be more like a hose. The third one felt the ear and decided the elephant was a fan. The last man, chanc- ing on the tail, assured the others that this "elephant" was nothing more nor less than a snake. Could we get an accurate idea of an elephant from any of these men? Can we, if we retain our narrow approach, ever hope to understand what makes the wheels go round in a Twentieth Century world?

The average veteran returning to Dartmouth is "eager." In most cases he comes back with a fixed purpose, older, knowing what he wants. Often he's married. That man no longer needs to be forced to study. What he needs is freedom and encouragement. Couple these with the enthusiasm within him, and near miracles can be worked.

When I came to Hanover as a freshman went on the theory that college was just as much social life and beer as it was books. Somewhere during the two and a half years I was in the Navy my ideas on that score changed. I think it was the time I saw wasted that did it. I swore that, once back at school, I'd go after the important things and not waste time getting grades. Of course I've sold out. I thought I could take what I wanted from a course and let the rest go. I did not want to carry any course past what I figured was the point of diminishing returns. But that couldn't be, and I'm in there scrambling for grades. Tuck School has many more applicants than it can handle, and grades talk. Thus I don't use my time as would profit me most, but rather squeeze every course dry in order to get a good-looking scholastic record.

The DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE is running a series of articles that will try to re-examine the basic tenets of Dartmouth and liberal education. If we mean to take the inquiry seriously, if we are interested in improving our college along any lines possible, we might ask ourselves a few questions. Does Dartmouth extend as much freedom as it might to responsible upperclassmen? Can there be no further extension of the Senior Fellowship principie? Secondly, does Dartmouth, with the funds at its disposal, attract the best possible professorial talent to Hanover? If it does not, why not?

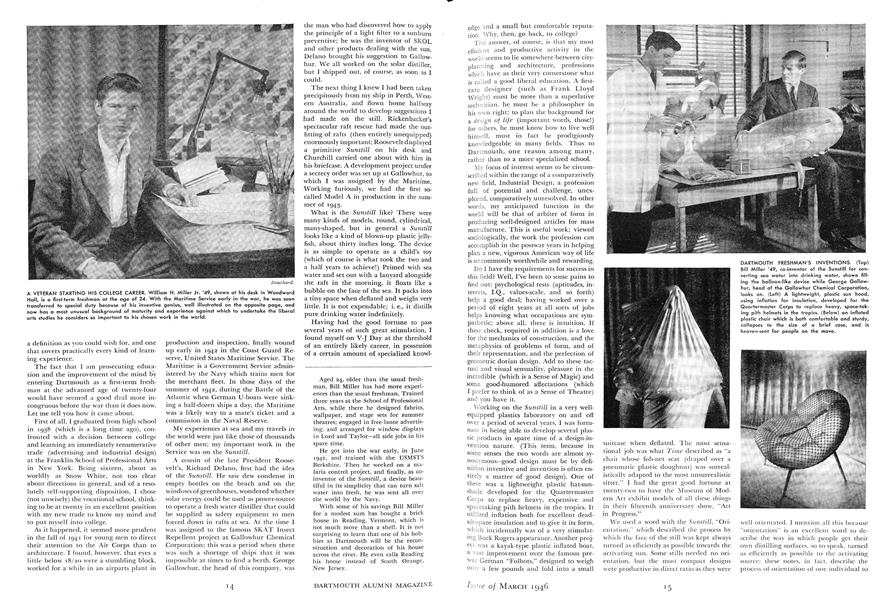

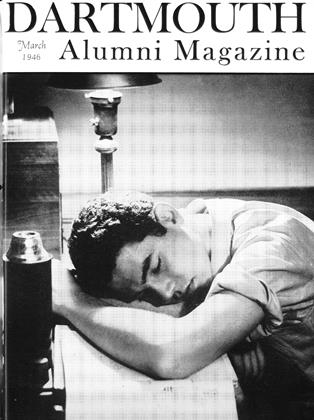

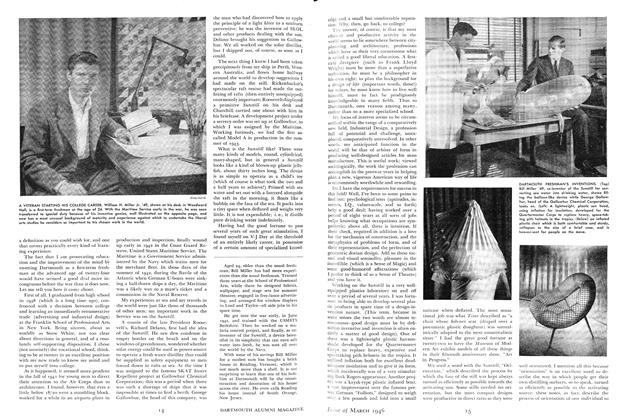

CAN YOU SPOT THE VETERANS in this freshman English class? Typical of the easy mingling of servicemen with other Dartmouth students is this class group of, left to right, front row: John N. Brewer '49, Marvin B. Durning '49, William H. Miller Jr. '49 (Maritime Service), Augustus P. Farnsworth Jr. '49 (Army Aviation Cadet). Second row: James R. Fowler Jr. '49, Ralph W. Burgard '49, John R. Hodgens '49 (Corpora, Marines), Louis J. Mulkern '49 (T/Sgt. U. S. Army). Third row: Jack R. Seiverling '49 (Pvt., Marines), David R. Raynolds '49, Norman W. Crisp Jr. '49 (Pvt., Army Air Forces), Richard W. Mallary '49.Against Against wall: William J. McMorrow '49, Ralph W. Sleeper '49 (Ist Lt., U. S. Army).

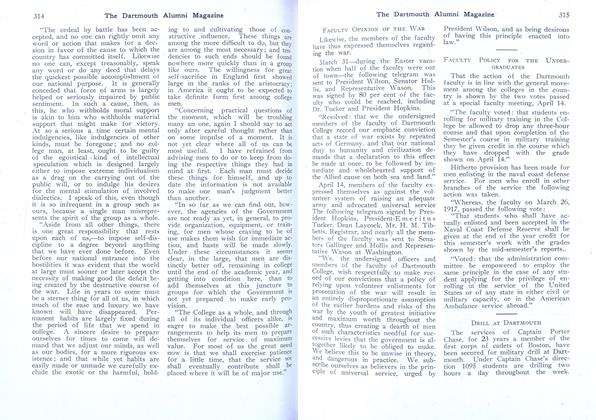

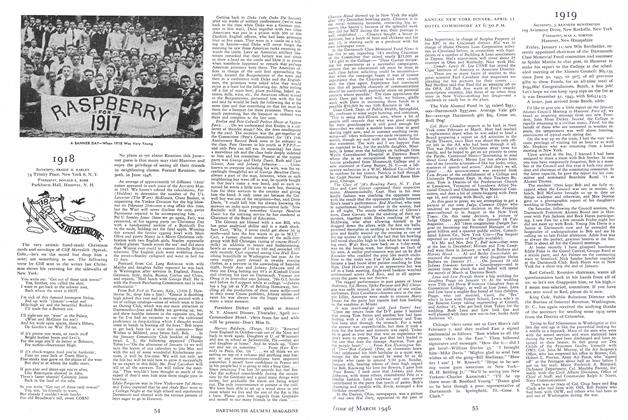

PRESENT AND PAST. Andy Scott '45, now in his senior year, finds skiing, his main winter hobby, quite a change from the days when he was flying a PB4Y-2 as an Ensign in the Naval Air Corps. Left, he is shown waxing up for an afternoon on the Hanover slopes. Below, Scott (second from the right in the back row) is shown with the officers and crew of the big Navy plane on which he served. Altogether he had 29 months of service, none of it overseas, and received his discharge last November.

PRESENT AND PAST. Andy Scott '45, now in his senior year, finds skiing, his main winter hobby, quite a change from the days when he was flying a PB4Y-2 as an Ensign in the Naval Air Corps. Left, he is shown waxing up for an afternoon on the Hanover slopes. Below, Scott (second from the right in the back row) is shown with the officers and crew of the big Navy plane on which he served. Altogether he had 29 months of service, none of it overseas, and received his discharge last November.

As Aviation Cadet and Ensign, Andy Scott flew many kinds of Navy planes in Florida and on the West Coast for two years and a half, ending up with PB4Y-2 Privateers. Back at Dartmouth, Andy finds that his attitude towards his own hobbies and intellectual interests prevents him from caring about success for himself in organized collegiate activities; and he has not joined a fraternity. Though he put in three years and a half here before the War and though he is already 23 years old, he is still unde- cided what he wishes for a field of con- centration and for a future career.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleA Very Wise Man Once Gave Me a Gloomy Warning

March 1946 By WILLIAM H. MILLER JR. '49 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

March 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleHANOVER HOLIDAY 1946

March 1946 By PROF. HERBERT W. HILL, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

March 1946 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, EDWIN R. KEELER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1946 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON