READERS TOO OFTEN of only one newspaper, undergraduates at Dartmouth College fail to inform themselves of the tremendous issues involved in the struggle for definitions as to what constitutes fair practices as understood by management and by labor.

The liberal college should do more than allow its students to worry in a vague way over what their parents are facing now with strikes and the constant threat of strikes. It should not be willing to allow its students just because the answers are difficult and subtle to slough off the questions that with so little time press for answers. It should take a positive stand and say that its graduates will belong one day to management, the professions, or labor and that though healthy skepticism based on intense mental activity may be praiseworthy, unhealthy prejudices are a consummation devoutly to be undermined.

Because of limited space, this article cannot claim to be as thorough as a semester's examination of the subject, but it will attempt to do what many undergraduates at Dartmouth (and graduates also, for that matter) say cannot be done: set a pattern by which one may test pragmatically the situation facing labor today.

Let us begin with a simple statement concerning the goals of labor during the last century and this.

American labor never has had fixed aims, but has changed its goals according to the economic state of the nation. Like- wise it has shifted constantly from a union structure that emphasizes a single class of labor, the skilled workers, to some kind of mass union.

To look more closely at this pattern, we have chosen the years 1846, 1896, and conditions today.

1846 FARM ECONOMY

If an 18-year-old recruit of the Continental Army looked about him in his old age, he would notice few economic changes from the America of his boyhood. Transportation had improved throughout his life from horse trails, to turnpikes, canals and railroads. The last, however, in 1846, were few in number and were just starting to merge into systems. Morse's telegraph had just been put into operation between Washington and Baltimore.

Most people still lived on small, nearly self-sustaining, farms or in towns. The number of cities in 1846 was scarcely greater than it had been in 1776 and all were still relatively small. The leash that checked them was lack of food. With the tools then in use, farmers could feed only themselves and one other family.

It was in the cities and larger towns that labor was organized. Although unions had been formed for a single strike since 1789, it was not until Jackson swept into the Presidency that continuous unions appeared. Jackson represented the frontier custom of universal male suffrage so that the eastern states, to hold their position, were forced to give up limitations on the right to vote.

American workers were the first in the world to get the privilege of the ballot. Workers thought the vote could lift all their oppressions. Hence, in the 1830s they formed city and state labor political parties. Their platforms demanded freedom from compulsory military training in the annual three-day musters, freedom from imprisonment for debt (some as small as 25 cents), a mechanic's lien which would make unpaid wages a first claim on the assets of a bankrupt employer, and a system of public schools.

The only schools ordinarily available to workers' children were "charity-schools." We have excellent authority for claiming charity as the primary virtue, but that applies to the giver not the recipient. Workers wanted education as a right, not a gift, and to be paid for by taxation. Said they, "Only an informed electorate is a safe one in a democracy."

These platform demands were supported by many liberal middle-class persons and therefore were adopted by the regular political parties as their own. When successful the credit for the reforms did not go to the labor political parties. This, with internal dissension and the terrible depression, which started in 1837, killed the labor parties and the unions that supported them.

After experimenting with various kinds of communal living during the depression, labor by 1846 had revived the unions. This time politics and social reform were forsaken for "pure and simple unionism," that is, organization by crafts, aiming at increased pay and shorter hours.

The forms, of labor organization between 1828 and 1846 had been two. The first was to unite by crafts locally, join all the independent craft unions into a city wide federation and then bring the various city federations into a national "Congress of Labor." This form was best for mass action in politics or social reform. The second type was to unite all the local unions of one craft into a national union of that craft. This form was most useful for "pure and simple" unionism. Up to 1857, all the unions of both types except those on railroads had no connection with power machinery and were formed by men engaged in simple handicrafts.

Inventors, however, were busy. Cyrus Hall McCormick, who had already created the mechanical reaper, was experimenting with other farm machines all of which were to find wide use during the Civil War, first to release farm boys for the army and later for work in cities. Charles Good- year had discovered how to make crude rubber useful by judicious mixture with sulphur. The sewing machine appeared in 1846. Rotary printing presses were on the way. So were anesthetics in surgery. These inventions together with more to come would utterly rout the simple living of 1846.

1896 AND THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

The significant fact about the industrial revolution was the use of labor in connection with power-driven machinery. Until after the Civil War the principal industries that had been thus converted were cotton and wool textiles, iron, paper and, of course, transportation by the railroad engine.

Between 1870 and 1896 nearly all the mechanized industries we now have—glass, pottery, and cigar making were the chief exceptions—were introduced, and almost completely blotted out centuries-old handicrafts in 26 years.

Labor's reactions to these rushing, overwhelming changes were two-fold; they formed some unions to oppose machines, and others to ride the crest of the wave of change. The Knights of St. Crispin, named for the traditional patron saint of shoemakers, was formed in the 1860s to prevent the introduction into the shoe factories of the McKay and Goodyear machines. After bitter defeats the union went into oblivion in the depression of 1872. The cigar workers (rollers) union kept up the fight against mechanisms in their trade from iB6O to 1917 meeting successive defeats, until today they exist only as an industrial union admitting to membership anyone who works in a cigar factory.

On the other hand, such powerful unions as the Molders, Machinists, Iron & Steel Workers, Printers, and Railway Brotherhoods were creatures of the industrial revolution and prospered with it.

Out of these conflicting tendencies three super-unions were created. Two of these, The National Labor Union, and the Knights of Labor were mass organizations aimed at social reform and legislation beneficial to labor. The third was the American Federation of Labor whose sole aim, according to its first president, Samuel Gompers, was "More." This meant more cents per hour, more recognition, more power.

The National Labor Union, headed by William Sylvis of the Molders Union was a catchall, including besides trade unionists, such other reformers as women suffragists, "greenbackers," freed Negroes, and almost anybody with a reform program. Sylvis himself was very nearly a socialist who corresponded frequently with Karl Marx. The death of Sylvis and the 1872 depression finished this organization.

The Knights of Labor, 1869 to 1896, also was open to anyone save lawyers, stock market speculators and dealers in liquor. Its declared aim was universal producers', consumers' and credit cooperation. By 1886 it was international in scope and was the largest, most powerful union not only in the United States but in the world. Legislation it demanded of the states and of Congress, it got. It also over- whelmed most employers. So the employers banded together to blacklist its members, scab its strikes—in which the A.F.L. helped—and rout it. Circumstances within and without the Knights played into employers' hands. After a short, glorious career it disintegrated when it joined the Populist movement in 1890s.

A predecessor of the A.F.L. was organized in 1881 and had Samuel Gompers as its president. In 1886 when the A.F.L. was formed, both Gompers and-the predecessor union (The Federation of Organized Trade and Labor Unions of the U. S. and Canada) joined it, Gompers again becoming president, this time of the A.F.L. He held this office, except for one year, until he died in 1924.

The A.F.L. had a slow steady growth and in the depression of 1893 did what no previous super-union had done—it survived. By 1896 it was challenging employers and the nation with a cry for "more." It needed "more," too.

The year 1896 ended an era of rapid mechanization, and free competition. Employers began to join their businesses together in pools, trusts and holding companies to suppress competition. Labor, on the other hand, had to meet the competition of hordes of immigrants. Because the trusts raised prices and the immigrants tended to lower the wage base, real wages in 1896 were at their lowest point since the Civil War. Agriculture, mechanized in this period, in 1896 was going over to specialization in money crops and manipulating prices upward. The year 1896 was labor's nadir.

THE PRESENT

The mere existence of a union powerful eough to compel an employer to accept collective bargaining limits the employer's freedom of action and shifts authority from him to the union. For this reason American employers fought unions by fair and foul means for more than a century.

At length employers discovered that they had less to fear from craft than mass unions. Not only have craft unions accepted the employer's theory of "free enterprise"—with all that is true and false wrapped in that term—but they are so self-centered that employers have been able to take them on piecemeal and pit one craft union against another. Employers thus retained a large measure of power.

Mass unions, on the contrary, are indivisible, and their form strengthens a program of reform. When such unions are backed by favorable laws and governments —town, state and federal—they may be a threat not only to an employer's power but to free enterprise itself.

Unfortunately for employers, the day of craft unionism seems near its end. By means of motion and time study, supplemented by moving pictures, every action of a skilled worker now may be known. Skill is no longer a "mystery." Like the jobs of common labor, those of skilled workers may now be divided and subdivided and consequently reduced. The prohibition of mass immigration in the 1920s has led to the substitution of machinery for muscle in unskilled tasks. Therefore, with the skilled pulled down and the unskilled pulled up to machine tenders, our labor force tends more and more to become a mass of quickly trained men and women.

As a result the very basis of the A.F.L., skilled trades, is being eroded. The A.F.L. must shift toward the industrial form or wither. The future seems to belong to some mass union whether or not it be called the A.F.L., C.1.0., or some as yet unborn union.

A mass union is effective in strikes but by its very nature must lean toward social and political policies. Hence a mass union is a power aggregate and must sooner or later challenge the power in the hands of large scale finance and big business. This means, too, .that the mass union in order to gain power will need at first the help of government, and then, having power, may find it necessary to exercise considerable control over the government.

Long ago the middle-class business manufacturers and merchants overthrew the power of landed gentry. Perhaps today we are in the first stages of a similar process, the overthrow of finance capitalism by the common man organized into mass unions and political parties. No union leader today may hold these views or have such revolutionary aims, but "there are tides in the affairs of men" that not only are irresistible "but lead onward to fortune." The tides seem flooding that way, not just in the United States, but all over the world. Since capitalism is most strongly fortified in the United States, and capitalists may be intelligent enough to share privileges with a mass union, capitalism may hold out here against the world's rising tide of socialism. Our future, then, depends more upon how labor organizes, or what are its aims, than it does upon the wisdom of capitalists in giving up a little power in order to preserve the rest of their powers.

The inherent tendencies in mass unions have not yet become dangerous because of the types of men who are union officers. Four out of five of them are Americans by birth, hence the old slogan that union leaders are "foreign born agitators" has lost point. A majority of the leaders attended American high schools and more than a third have had the benefit of college training. The average salary of a labor leader is $8,000 a year, and only one man makes as much as $30,000 a year. These figures are distinctly below those of the industrial managers with whom union officers bargain. Moreover, the average union leader is younger than his industrial counterpart.

These statistics—gathered by Professor Miller of the University of Maryland in 1945—are more applicable to the C.1.0, than to the A.F.L. They apply to the A.F.L. in levels below the top where officials change less often than membership of the United States Supreme Court.

The outstanding demands of union leaders today are for (1) a guaranteed minimum annual wage for workers, (2) a yardstick for measuring wage rates—average efficiency of an industry has been suggested— (3) the closed shop and (4) full employment. There is nothing revolutionary in this program.

Our future depends upon how labor organizes and what are its aims, and also upon the wisdom of capitalists in avoiding another depression like that of the 1930's. Another such experience as that very well might turn Americans into revolutionists. Labor always marches with the times.

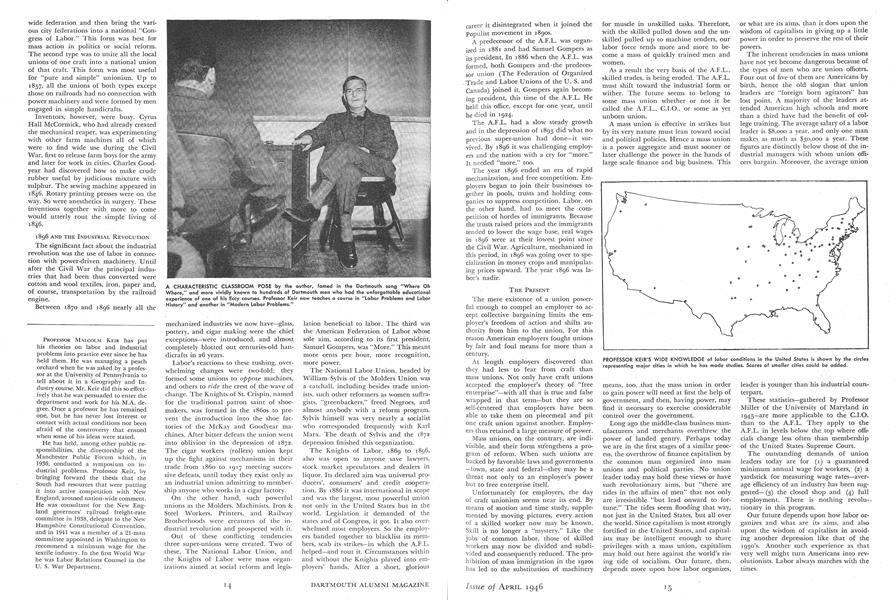

A CHARACTERISTIC CLASSROOM POSE by the author, famed in the Dartmouth song "Where Oh Where/' and more vividly known to hundreds of Dartmouth men who had the unforgettable educational experience of one of his Eccy courses. Professor Keir now teaches a course in "Labor Problems and Labor History" and another in "Modern Labor Problems."

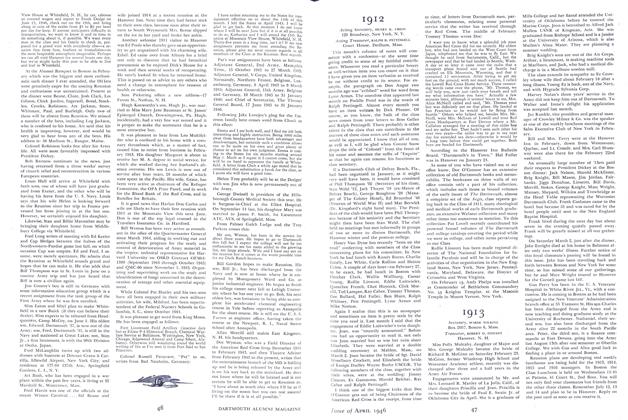

PROFESSOR KEIR'S WIDE KNOWLEDGE of labor conditions in the United States is shown by the circles representing major cities in which he has made studies. Scores of smaller cities could be added.

PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS

PROFESSOR MALCOLM KEIR has put his theories on labor and industrial problems into practice ever since he has held them. He was managing a peach orchard when he was asked by a professor at the University of Pennsylvania to tell about it in a Geography and Industry course. Mr. Keir did this so effectively that he was persuaded to enter the department and work for his M.A. degree. Once a professor he has remained one, but he has never lost interest or contact with actual conditions nor been afraid of the controversy that ensued when some of his ideas were stated. He has held, among other public responsibilities, the directorship of the Manchester Public Forum which, in 1936, conducted a symposium on industrial problems. Professor Keir, by bringing forward the thesis that the South had resources that were putting it into active competition with New England, aroused nation-wide comment. He was consultant for the New England governors' railroad freight-rate committee in 1938, delegate to the New Hampshire Constitutional Convention, and in 1941 was a member of a 21-man committee appointed in Washington to recommend a minimum wage for the textile industry. In the first World War he was Labor Relations Counsel in the U. S. War Department.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleTHE NEW CURRICULUM

April 1946 By PROF. HUGH S. MORRISON '26, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

April 1946 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, EDWIN R. KEELER -

Article

ArticleEducational Aims

April 1946 By PROF. CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

April 1946 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, RUFUS S. SISSON JR.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMEETING OF SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

February 1916 -

Article

ArticleMILITARY TRAINING CAMP QUOTA IS INCREASED

March, 1926 -

Article

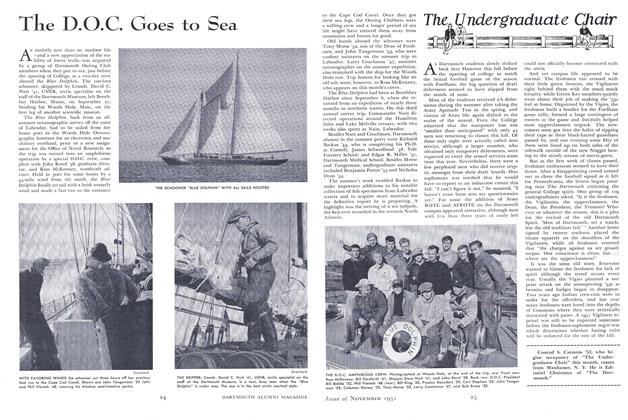

ArticleThe D.O.C. Goes to Sea

November 1951 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

MARCH 1963 -

Article

ArticleSQUASH

FEBRUARY 1967 By DAVE MARTIN '54 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

January 1947 By G. W. Woodworth