The Philosophy Behind the Revised Curriculum

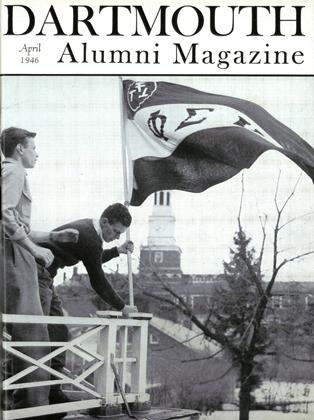

THE CURRICULUM which goes into effect with the class entering Dartmouth this fall is, as Professor Morrison has indicated in his article, more a modification than an innovation. The modifications in substance are designed to afford the student in his first two years a wider acquaintance with the various areas of knowledge, and to treat these areas as general education rather than as vocational or specialized preparation. The one novel feature of the revised program is the proposal by Dr. Dickey of a course in "Great Issues," required of all seniors, a course which will help the student about to enter on his career to envisage more realistically the problems and responsibilities of an adequate citizen in our complex and troubled world.

Except for this senior course, the revision of the curriculum has been an enterprise largely worked out by a sub-committee of the Committee on Educational Policy in cooperation with the executive committees of the three Divisions of the Faculty. The executive committees took the joint proposals to the members of their Divisions for discussion and subsequent approval, modification, or rejection. This has meant a genuinely democratic procedure, but it has also meant considerable compromise.

The authors of these two articles on the curriculum, who were both members of the sub-committee, still feel, perhaps very naturally, that the program which we brought to the Committee as a whole last May is in several respects superior to the one eventually adopted by the Faculty. In particular, we proposed that the study of foreign language be optional, and that the requirements in science and social studies be met by taking either divisional survey courses or the existing departmental courses. We thought that advisers should recommend foreign language work to those students who would be likely to need the language, and that many other students would elect languages who find other values or pleasure in such study. We are convinced that for many students the study of language is unrewarding. On this issue, however, our point of view was shared neither by the Committee as a whole nor by the Faculty in general.

Wishing the curriculum to be as adaptable as possible to the purposes, interests, and needs of individual students, we proposed that the science requirement be met by taking either departmental courses, as at present, or by two years of survey courses, the first treating physics, chemistry, and astronomy, the second botany, zoology, and geology. (Since our formulation of these survey courses, Harvard and Yale have proposed similar courses, required, however, of practically all students—not so flexible an arrangement as we had in mind.) Likewise, in meeting the social science requirement we proposed the same two types of courses, departmental courses intended for majors in social science, and survey courses of an interdepartmental character: die freshman course to be essentially historical (with emphasis on international relations), and the sophomore course a choice between a survey of economics and government and a survey of psychology, geography, and sociology.

The Division of the Sciences strongly repudiated the survey course idea. The Division of the Social Sciences sympathized with the survey course idea but found very few members eager to conduct such courses. Compromise proposals emerged from Divisional conferences, compromises which the sub-committee believes somewhat better than present requirements but less attractive than the sub-committee's original proposals.

William James, after he had labored twelve years on his monumental Principles of Psychology, was so disgusted with the subject that he referred to psychology as a "nasty little science." It is possible that the sub-committee, after working two years on curricular detail, might have felt a similar disgust with its project except for two beliefs. Although we were disappointed that our original proposals were not adopted, we nevertheless believe that the curriculum has been brought in several respects into better accord with what we consider desirable educational philosophy. But even more important, from the start of its deliberations the sub-committee has believed that curricula do not produce miracles or geniuses, that in the educational experience curricula are much lessimportant than faculty, students, and the manner of teaching. Effective education seems possible to us with a wide range of curricula very unlike one another. Consequently, we cannot believe that the curriculum adopted by the Faculty on February 15, in the Year of our Lord 1946, or any other curriculum, will either create an educational Utopia in Hanover or, as one disgusted Faculty member expressed the fear, bring about the degradation of Dartmouth College. To the sub-committee what is studied at Dartmouth College, although this is not unimportant) is rather less momentous than who is studying, for what purpose he studies, under whom he studies, what the method is of communication of minds, and to what fruitful activities during and after college the stimulation of Dartmouth leads. What is signally important is that we make courses as meaningful as possible in the thinking, and as vital as possible in the living of each student.

With this outlook, the sub-committee very naturally devoted several of its early meetings to discussions of a guiding philosophy. Dartmouth College, in our opinion, can best contribute to the future if the College is primarily and predominantly concerned with humanity rather than technology; if its educational spirit is amateur and personal rather than professional; if its programs are planned for the student rather than the professor; if in the operation of its curriculum it recognizes that function is more important than content; and if in its instructional procedures it stresses responsibility rather than discipline, thus making discipline a positive means to an end rather than in itself a vague and vacuous end.

In recent decades vocational courses have increased in number and appeal in American colleges, including liberal arts colleges. The availability of such courses for election is probably both necessary and wholesome, provided it does not suggest to students a magic road to success, a road which circumvents the fundamentals of the arts and sciences, including those arts and sciences which particularly contribute to an understanding of man and society; and provided it does not suggest to students that society exists for technology rather than technology for society. The outstanding leaders of professions and industries have recognized that professional and technological progress is most certain, most meaningful, and most continuous if it has the foundation of a broad culture. It would be lamentable if liberal arts colleges did not recognize as much in their curricular planning. There is no need to exclude vocational courses from the curriculum of men preparing for medical and other professional careers. It is both possible and desirable, however, that such courses quantitatively constitute a lesser portion of every student's curriculum, and that they qualitatively fit into a liberal arts curriculum, both by proper articulation with a liberal arts background and by the maintenance of a constantly humane outlook.

Although data show that students who have made vocational decisions tend to pass their courses with higher grades, it does not follow that education at Dartmouth would improve with more stress on the professional view of the areas of knowledge. Indeed, the vocational value of courses will be enhanced not by making these courses more immediately concerned with the specific professional details of engineering or medicine, law or business, but rather by showing the significance of these professions to the life we live or might conceivably live. The professions exist to meet human needs and to fructify human living. The inadequacies of the professions in the past and in the present have been attributable not so much to the lack of technological knowledge as to the lack of human understanding.

As most colleges are organized, it is the professors rather than the students who are educated. Through intensive reading and constant thought, through interrelation, organization, and expression of ideas we enlarge and clarify our intellectual comprehension. If these are the processes by which the professors have learned most, why should not these be the processes by which the students learn? Even if by such individual reading, organization, and interpretation of knowledge—in short, by the more active participation in the educational process—students could not encompass as great a portion of the intellectual universe as can be presented in the academic digests of faculty members, still would not the actual education be more personal, more integral, more real? Dartmouth College has the facilities for such an active education, both in the resources of Baker Library and in guidance by the Faculty. It is time for education by impression to give way to education by expression.

Teachers are not unimportant in education by expression, but they are important more for the functioning of their minds than for the content of them. Great teachers have always engrossed not only the intellects of their students, but the emotions and drives as well. In lesser degree all of Us have our happy moments in teaching when we are able to arouse our students totally. At such moments we are not mere dispensers of information, completely wrapped up in the content of our courses; we have begun to function in the lives of our students, helping them to discover a relationship between fact and life and to be stirred by that discovery. It is idle to plan a content of education without giving thought to the way such content will function in the lives of men.

There has been much talk of late about the viciousness of political and economic isolationism. Social and moral isolation are quite as reprehensible. In such times as ours, in which to the most imperturbable of us men appear confused and uncertain, and to the most anxious of us it seems as though mankind were on the brink of chaos, it is little short of madness for us to assume an ivory-tower view of education, and culpably schizophrenic for the student to regard knowledge as existing for knowledge's sake. We have a responsibility to the society that has nurtured us, and today more than ever before it would be tragic for us ever to be unmindful of that responsibility. Whether we work for a world well-housed, well-clad, and wellfed, or a world freed from the ravages of physical and mental malady, whether we try to create for the world new Eroica symphonies, Sistine frescoes, Taj Mahals, or Divine Comedies, or make our utmost contribution to a world of peace assured by understanding, good-will, and love, there are tasks for knowledge and desire to undertake, responsibilities to our perplexed world which colleges, particularly American colleges, must bear.

It is obvious that merely changing a curriculum will not enable Dartmouth to achieve these objectives. A new envisagement of our courses, their personnel and purposes, new ideas of teaching, and a new inspiration for our objectives are essential for this curriculum or any curriculum to be worthy of the best ideals of Dartmouth College, for this College to become, perhaps in a new sense, vox clamantis in deserto.

CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATIONAL POLICY, Prof. Charles L. Stone '17 of the Psychology Department has been in the thick of Dartmouth's postwar curriculum studies for the past three years. His analysis of the Committee's general views is presented in this article on the new curriculum.

CHAIRMAN, COMMITTEE ON EDUCATIONAL POLICY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleLabor Marches With the Times

April 1946 By MALCOLM KEIR, -

Article

ArticleTHE NEW CURRICULUM

April 1946 By PROF. HUGH S. MORRISON '26, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

April 1946 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, EDWIN R. KEELER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

April 1946 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, RUFUS S. SISSON JR.