Its General Character and Important New Features

CHAIRMAN OF THE SUB-COMMITTEE ON THE CURRICULUM, COMMITTEE ON EDUCATIONAL POLICY

THE CURRICULUM TABULATED BELOW is not a "new" curriculum in the sense that sweeping changes are fnvolved. It embodies Dartmouth's traditional purposes as a liberal arts college and preserves the major outlines of the curriculum used for the past generation. There are, however, many changes in detail and at least two important innovations. It is the purpose of this article to explain what these changes are, and some of their educational implications.

The primary purposes of the distributive requirement in freshman and sophomore years are, first, to broaden the student's general education in those fields of thought which will lay a foundation for his intelligent action as man and citizen, and second, to introduce him to the chief fields of knowledge so that he may be able to make an informed and intelligent choice of his major study.

Both of these objectives make it important for all students to be introduced to a wide variety of fields of knowledge. The new distributive requirement accordingly includes a wider range of subjects than does the present one. The student now takes nine different subjects; in the future he must take from ten to thirteen. Taking a course in a subject is, in a sense, opening a door. Ideally, all educated men should be able to learn any new field by reading books. In practice, however, a subject in which he has never had a course is likely to be "Greek" to the average graduate and remain so throughout his life. Taking even one course gives the student a speaking acquaintance with the terms and outlook of a field of knowledge which is inevitably extended by the experiences of later years, and which can be readily deepened by further study.

This process of "opening doors" is an essential characteristic of liberal education as opposed to specialized technical education. The latter assumes a limited horizon and a fixed goal; it assumes that the student knows what he wants to do, can predict what subjects he needs to achieve vocational competence, and that the faculty can teach him those subjects. The former assumes a limitless goal: that our job in the liberal arts college is not to teach a student what he is to know, but to extend his intellectual horizon and increase his capacity for learning, throughout life, in endeavors and fields that we cannot now even guess at. The one regards education as a product, the other regards it as a continuing process.

We must accept the fact that we simply cannot teach the student in four years all that he ought to know as an educated man. What we can do is to teach him enough of the basic vocabulary and the kind of thinking represented in the major fields of knowledge to enable him to learn more by himself.

The increased range of subjects is obtained, in part, by an increased amount of prescription: the distributive requirement at present takes 60% of the average student's time during the first two years; in the future it will require 70%. The increase occurs, specifically, in the Division of the Humanities where, for the first time in recent decades, something more than English 1-2 and a foreign language will be required of all students.

Despite increased prescription, the new curriculum allows a good measure of freedom. There is some room for choice within groups of courses forming the distributive requirement, and the relatively large amount of prescription in freshman and sophomore years (when it is, from the standpoint of orientation, most desirable) is offset by considerable freedom in junior and senior years. In his four-year program the student will devote fourteen semester courses to the distributive requirement in general education and fourteen semester courses to free electives. This seems a reasonable balance.

The increased range of subjects in the new curriculum is also achieved in part by increased emphasis on one-semester introductory courses rather than year- courses. The new one-semester introductory courses in most departmental fields will be designed as ends in general education rather than as means toward specialized education, being intended to contribute toward broad intelligence in the arts and sciences rather than as factual or technical drill-courses considered merely as prerequisites for advanced specialized work. The faculty as a whole believes that such one-semester courses can successfully be given, and that what a one-semester course loses in scope and thoroughness, as compared with a year-course, is more than offset by the increased range made possible in the curriculum.

The decision to emphasize one-semester departmental courses is in opposition to the current trend in American higher education toward comprehensive interdepartmental "survey" courses. The latter have grown up in response to the same needs for breadth and orientation that have been felt at Dartmouth; there is no question that they are valid in principle. They have advantages over departmental courses in that they can be broader and more inclusive in coverage and can demonstrate more effectively the inter-relationships of the fields of knowledge.

The sub-committee on the curriculum originally recommended the introduction of six new courses of this nature, but the suggestion did not meet with favor. Opposition was strongest in the Division of the Sciences, which voted informally almost nine to one against any such innovation. The Division of the Social Sciences favored such courses in principle, but felt that practical difficulties, especially in staffing, militated against them. The humanists (apparently more experimentally minded than the scientists?) are going to try one— the new "Humanities 11-12," a course in Classics of European Literature and Thought, which will deal with the western cultural tradition through a number of great books. It will be taught by an interdepartmental staff and promises to be an extremely worthwhile venture.

To be sure the "survey" type of course is not the one indefeasible answer to the problems of American liberal education. It is a difficult type of course to organize and teach, it involves complexities in staffing and administration, and it usually takes several years' experience to develop properly. The traditional departmental course, on the other hand, is based on long experience and accumulated skills in instruction and is of course a safer venture.

One important innovation is the adoption of the principle of "proficiency exemptions." A year-course in secondary school normally has 123 contact hours. It may well succeed in teaching the student as much as a one-semester college course (35 contact hours) or, in certain cases, as much as a year-course. Under the new regulations, a student who can demonstrate proficiency at the college standard in the work of any course or courses included in the distributive requirement for the degree will be exempt from such courses and from a corresponding number of semester hours in the divisional requirement involved. The hours thus released may be used for free electives in any field.

The adoption of this principle, and its application to every course and activity included in the distributive requirement of freshman and sophomore years, including Physical Education and Hygiene, is an important forward step. It permits the able and well-prepared individual to progress more rapidly to advanced work, and it should be a considerable encouragement to future secondary school students to make their school work count.

The only change in the foreign language standard is the addition of the proficiency exemption system to the present rather complicated requirement. Provision has been made, however, for the adoption of modern methods of teaching languages through optional "intensive" courses carrying double credit. These will have a large number of contact hours per week and will develop both reading and speaking ability.

The course in Hygiene has been modernized in both content and methods of instruction in recent years. Covering important material in the fields of human physiology, physical and mental hygiene, it will be extended through both semesters of freshman year, and will receive hours and points credit.

In the Science Division, Astronomy 1 and Zoology 3 will be new one-semester introductory courses, intended primarily for the general student rather than the prospective science or medical major.

No important changes have been made in the provisions for the major study. Five year-courses in one department will continue to form the standard major. There is now, however, an opportunity for flexibility in the distribution of these courses in sophomore, junior, and senior years. The existing "modified major" is to be continued. This is intended to fit the needs of students who have a definite interest in the major department but who are also interested in some specific problem or topic, the study of which depends on related courses in other departments. The modified major provisions are flexible enough to permit a wide variety of "individualized" major programs. The "special major" program is even freer, since it involves no departmental limitations. Special majors must, however, comprise a coherent program of advanced character, and it is unlikely that they will be approved by the Committee on Educational Policy except for students of marked ability.

By all odds the most significant feature of the new curriculum is the course on "Great Issues" to be required of all seniors. The idea for such a course was first broached to the Committee on Educational Policy by President Dickey. As plans for the course develop, a more comprehensive account than is possible at this time will doubtless appear in a later issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. This article would be incomplete, however, without some report on the "G.I." course; in the view of the Committee on Educational Policy, it forms an integral part of the whole structure of the curriculum and will contribute signally to the achievement of the purpose of the College.

Ernest Martin Hopkins has said of the liberal college: "Its major obligation still is to human society and its principal solicitude is that civilization continuingly shall benefit from the absorption into itself of individuals who are better and wiser and more competent and more cooperative than they would otherwise have been. Specifically, this is today the principal concern of Dartmouth College." The College's primary objective of serving society requires that it graduate men of skill and knowledge, and men also able to put such skill and knowledge to good use. Dartmouth men will be thrust into the thick of local, national, and international, problems from the moment they graduate. It is not enough that they should be sideline philosophers. They will have the responsibility of making decisions and taking action in public affairs.

One of the chief purposes of the curriculum of freshman and sophomore years, it was stated, is "to broaden the student's general education in those fields of thought which will lay a foundation for his intelligent action as man and citizen." It is the specific purpose of the course in Great Issues to bring the foundation knowledge acquired by the student in the first three years of college into sharper focus on the great national and international problems of the world today which he must confront as an acting citizen.

These problems will vary from year to year. They will range over the whole realm of the sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities—indeed, most of them will not be- susceptible of such neat division. One thinks most readily of such problems as the UNO, industrial strife, military preparedness, race prejudice, Russian foreign policy, atomic energy, Colonialism, and so on. But sometimes a great book or a drama springs up as a moving human issue, or a new philosophy or work of art; sometimes less inflammatory issues such as socialized medicine, the metric system, Basic English, the world calendar, or the conservation of natural resources, demand attention. Certainly there should be no fixed proportion of "fields" and no inflexible program.

The conduct of the course remains to be determined. A special director will be appointed, and he should of course have freedom in working out details. On each issue, an authority of national distinction will lecture, and if possible, remain, in Hanover a day or two for group discussions. On controversial issues, opposing viewpoints would be presented by different men. Some of those so far mentioned as possible visitors leave no doubt that the College will be seeking top-flight men who have had a wealth of experience and who have something to say. Students might be prepared for such lectures by "briefing" sessions conducted by various members of the faculty.

A special room in Baker Library will probably be devoted to the assembly of literature on each issue. In particular, the student would be expected to read the comparative treatment of an issue in the headlines, news stories, and editorials of several widely dissimilar newspapers, such as The New York Times, the ChicagoTribune, The Washington Post, PM, and the Hearst press. This would teach him something about newspapers. Magazines such as Life, Collier's, the New Republic,Harper's, and Foreign Affairs would be open and marked for parallel study. TheCongressional Record and governmental bulletins would be on hand. A small shelf of books would be collected for the study of each issue; even if the student did not read all of them, seeing them would give him some idea of the material available for serious study and a realization that behind every headline of today is a book of yesterday.

It is felt that the Great Issues course should be for seniors, and seniors alone. Presumably they will be the most ready to take advantage of it, and they will be the first to go out into the wide, wide world. It would give the senior class the sense of unity achieved by a commonly-shared intellectual experience, and it would sharpen their sense of the purpose of their college education as they approach the commencement of their lives as citizens.

The new curriculum establishes the structure of courses in the four-year program. Needless to say, many other things enter into successful education. The Committee on Educational Policy is particularly interested in plans for increasing the student's participation in the educational process, and for improving methods of student guidance. These and other matters which may contribute to the improvement of education at Dartmouth will be studied further and presented to the faculty for consideration at a later date.

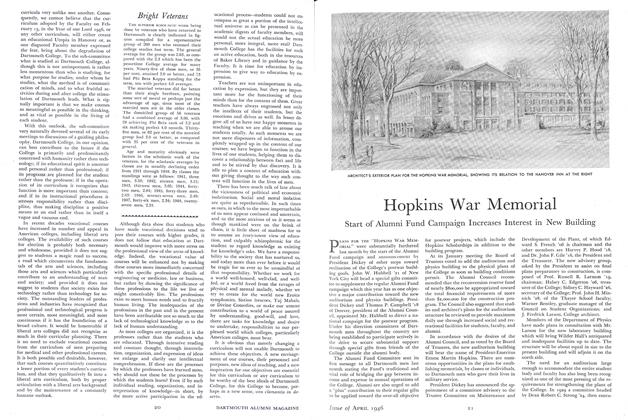

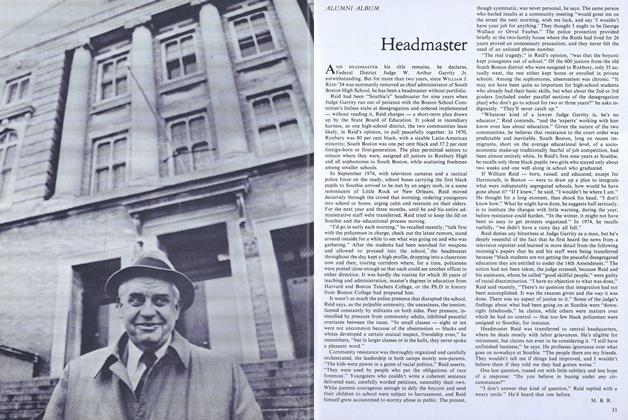

A LONG-STANDING INTEREST IN LIBERAL ARTS CURRICULA was an invaluable background for the important job which Hugh Morrison '26, Professor of Art, was given as chairman of the sub-committee on the curriculum when, the Committee on Educational Policy tackled revision of degree requirements.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleLabor Marches With the Times

April 1946 By MALCOLM KEIR, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

April 1946 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, EDWIN R. KEELER -

Article

ArticleEducational Aims

April 1946 By PROF. CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

April 1946 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, RUFUS S. SISSON JR.

PROF. HUGH S. MORRISON '26,

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY AND COLLEGE VACATIONS

December, 1912 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN RECEPTION

-

Article

ArticleTUCK SCHOOL STAGE DELCO LIGHT CO. SALES CONVENTION

January 1921 -

Article

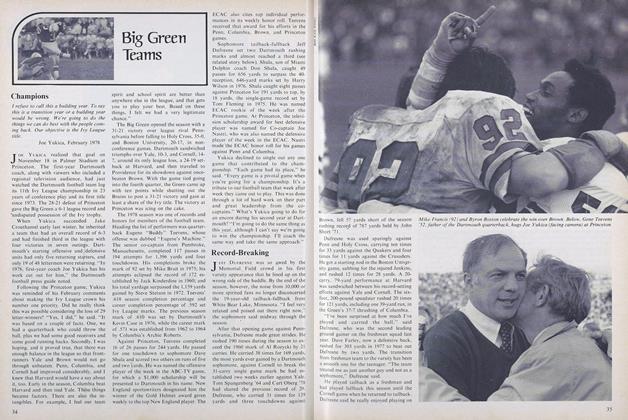

ArticleRecord-Breaking

December 1978 -

Article

ArticleHeadmaster

APRIL 1978 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticlePROPAGANDA AND THE CRISIS

May 1947 By MICHAEL E. CHOUKAS '27