ONE FACT STANDS OUT most COnspicuously above all. That fact is—the life of the editor in this bewildering twentieth century is not an easy one."

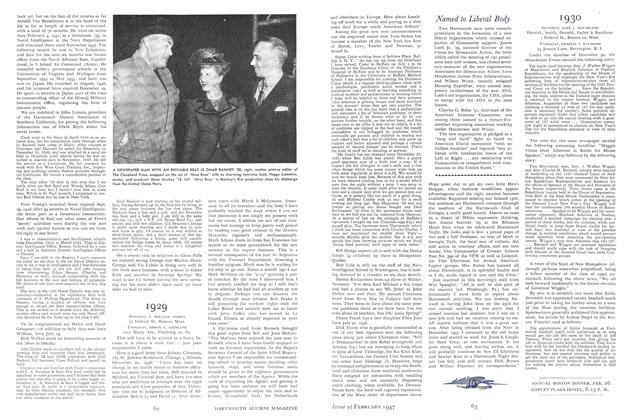

The speaker was a slight, and sandyhaired man. His eager intensity was almost boyish, but the sparsity of his sandy hair belied boyishness.

"You have few landmarks to chart your course in these kaleidoscopic days," he went on. "You must be fleeter of foot and nimbler of mind than any of those who went before you."

The speaker was one of the most successful newspaper editors in America today. He addressed 25 men seated around a huge walnut table shaped like an elongated doughnut.

He was Louis Seltzer, editor of TheCleveland Press. The 25 were managing and news editors of leading newspapers from Massachusetts to California. It was a campus scene. But they were an intent, sober lot—average age 44 years. It was a session of the American Press Institute at Columbia University.

Fortunately for you and me, it would be difficult to find any group with a deeper sense of responsibility than this one. We live in a world in which literally almost anything can happen overnight. And no one can do anything about it but you and me. We must be told, as promptly and accurately and understandably as possible, what is going on.

We live in a confused and conflict-torn world, a world in which we know from woeful recent experience whole peoples may be gripped with a murderous mass neurosis. And in which weapons to blot out whole cities may be shot to a distant continent in a few hours.

The only possible protection is an enlightened and informed citizenry. There are no all-wise, benevolent rulers on whom we may blindly depend. There is no place on this planet, suddenly made small, where we can safely hide. You and I and every other citizen must be told, promptly and understandably, what is going on

Our daily newspapers, and the world- wide news collecting instrumentalities which they maintain, are our primary, basic source of information as to what is happening, either in far places, or in our immediate communities.

But the task which our newspapers undertake for us has grown incredibly enormous. Another distinguished newspaper man told this same group of 25 editors, "We run the risk in this fantastically complicated world of creating mere confusion. Unless we brilliantly improve our skills and techniques, we face what may be described as a crisis of meaninglessness."

Certainly, if the collective genius of men has created a world which is so far beyond the scope of rational democratic decisionif, indeed, we face a crisis of meaninglessness then our civilization is doomed.

But take courage. The newspaperman who raised that specter of meaninglessness is one of many leaders in the dissemination of public information who are not only deeply concerned about the problem, but who are doing something about it. He was Sevellon Brown, editor and publisher of the Providence Journal, who originated the idea of the American Press Institute.

The Institute, founded by 38 publishers, is seeking to improve the effective public service of American newspapers by holding intensive, two to four-week seminars for editors and top-flight reporters. It is representative of an increasingly zealous determination among disseminators of news and information to meet the challenge of this all too fearsome new world.

However much these zealous leaders in the newspaper profession labor, it will help if you and I and our fellow citizens who are on the receiving end of newspaper service can have a better understanding of its basic and vital function in our democracy. An amazing proportion of the critical writing about newspapers has been of the wild-eyed expose variety. Some of it is constructive. Much of it is utter bunk.

We have been told that the newspaper is a dying medium, that it is being supplanted by the radio, the news magazine, and may face virtual extinction when television and other marvels of science just around the corner come into early popularity. We are even told that newspapers are being kept alive only by comics and other circulation- getting features.

The fact of the matter is that the printed word is a very, very long way from being supplanted by any other form of communication. Man's physiological perceptive machinery being what it is, the eye is far more accurate than the ear. For some years, newspapers were nervous about news going out competitively over the air. But now they find circulation actually goes up when a big story is first reported on the radio. Having heard it, people want to read about it.

There is no substitute for the printed word as a conveyor of information. It can be effectively supplemented by pictures, charts and diagrams, and progress in pictorial journalism is making tremendous strides. Kent Cooper, executive director of The Associated Press, startled a group of editors a few years ago by predicting that the newspaper of tomorrow would be half text and half pictures. There is a Chinese proverb that one picture is worth ten thousand words.

But the picture catches one instanta- neous facet of any happening. Even picture magazines have found that they must increase the amount of text with pictures. One day not far distant, we shall doubtless be able to sit in our homes and see and hear debates in Congress with our radio-television sets, as effectively as we now can by sitting in the visitors' gallery. But few of us will have time for that. We shall still depend upon our newspaper.

We have been told that our newspapers are monopolistic, that they are big business, that they distort the news, or tell us only what they want us to know. Critics of the press have made much of the fact that in 1944 only 22 percent of the daily newspapers supported Roosevelt, while his popular vote was over 53 percent.

Anyone familiar with the history of journalism in the United States over the past century can scarcely be discouraged by that argument. The fact is, newspapers in this country have evolved from an era of small newspapers, vehemently biased and dedicated primarily to plugging for a definite, usually selfish objective, to the great newspaper of today which strives to tell all of the significant news as objectively as humanly possible.

Thoughtful people generally, I believe, recognize that no President, no candidate for the Presidency, was ever more fully reported in what he did and what he said than was President Roosevelt. In earlier times of the much vaunted individual journalism, newspapers devoted themselves almost exclusively to bruiting the virtues of their favorite candidates. The progress made in divorcement of editorial opinion from the newspages of our newspapers is a great historic achievement. In very few countries has this been done so completely, and, of course, in several not at all.

The American correspondent of a great European newspaper said to me the other day, "This objectivity you keep talking about is mostly rot. No human being can be truly objective. Every individual is full of subconscious bias of which he is unaware. How he will see and report anything that happens is conditioned by his whole background of experience, education and culture. A reporter worth his salt owes it to his readers to praise and condemn, to say bluntly what is good and what is bad. How could any decent man blandly report the doings of a Hitler without condemnation?"

I replied, "Journalism is a human profession, and will never rise above human fallibility. But there would have been no such flowering of civilization in our western world if men had not striven constantly to rise above their prejudices and their emotions. I do not claim that any man can attain complete objectivity, but a newspaper reporter or editor can do his level best, and the record shows he can go a very long way toward the goal of objectivity. When he does he is effectively performing his vital function in this democratic world.

"The trouble is, when a reporter sets himself up as a superman to tell his readers what is good and what is bad, he is not very effective. He then becomes a special pleader. Special pleaders are suspect, and whatever they say immediately goes at a big discount. Sound rational decision is reached in public matters when the citizens make up their own minds on the basis of facts understandably presented. I do not believe that any amount of condemnation of Hitler would have aroused America to the full awareness of the menace of Hitlerism. What did it, was excellent reporting of what he did and what he said. The reports of Hitler's speeches alone—many newspapers ran full texts—effectively exposed his viciousness to most Americans."

America is fortunate in that the tradition of objective news distribution began to develop rapidly here soon after the invention of the telegraph. America's first great news agency began in 1848, called The Associated Press. Out of it grew the great, cooperative, non-profit Associated Press of today, owned by the newspapers it serves. It must make its reporting as objective as humanly possible, to satisfy newspapers of extreme diversity of editorial leanings and persuasions. The other two principal American agencies—the United Press and the International News Servicewhile profit-making corporations, are owned by newspapers and are dedicated to the service of newspapers. They have developed in the same tradition of objective news reporting.

Now what of the charge that newspapers are big business, are often monopolistic? It is true that there has been a marked tendency in the past quarter century toward newspaper mergers, and many cities have only one newspaper, or two newspapers owned by the same publisher. It seems obvious that this trend reflects primarily the economic development of this mass production age. Newspapers have greatly expanded their services to the public, both in content and in distribution. Newspapers are bigger and thicker, and they are delivered rapidly over greatly expanded circulation areas. Of course, this has greatly increased the plant, equipment, organization and capital required.

Certainly one result is far better newspapers. One strong newspaper can do a far better job than three or four weak ones. Also, a strong newspaper is far more secure in its independence than one which is in constant financial jeopardy. I doubt if many well-informed persons seriously believe any more that newspapers are influenced by advertisers. After all, newspaper men are human beings, and there will always be black sheep among them, just as there will be in any other profession. But the general standard of professional ethics in journalism is extremely high. Furthermore, almost every newspaper man knows it is just poor business judgment to let an advertiser even try to dictate editorial policy.

But how monopolistic is a newspaper in a single newspaper town? Such a newspaper certainly cannot thrive for any considerable period of time without the respect of its readers. The individual has many sources of information, including radio stations, newspapers from other cities, magazines and innumerable specialized publications issued by professional, religious, fraternal, trade, labor, scientific, educational and other groups. Never was so much printed matter dealing with current problems cheaply available to the individual. The newspaper which suppresses significant news will soon be found out.

Yet the question is frequently asked, "Do we have a free press?" I doubt if there will ever be a universally affirmative answer to that until printing costs drop to the point at which every man can have a newspaper especially prepared for himself. But that might not be desirable. It would not be good for us to be able to read only what pleases us. The philosophical basis of our civilization is that we arrive at truth through free and unrestricted association of ideas and information.

It is true, however, that Americans do not like anything that has even the appearance of monopoly. It seems probable that technological change may sometime greatly reduce the cost of printing a newspaper, and that we will then have more newspapers. But I hope they will remain general newspapers dedicated to presentation of all the significant news. I know of no reporting so bad or so biased as that which appears in certain specialized publications issued by certain highly zealous groups.

Probably we newspaper men are over defensive. But I think most of us welcome constructive criticism. Not a little of the censure of the press comes from fanatics who consider the reporting of opposing viewpoints intolerable. If newspaper men are over defensive, this doubtless stems from the long years of struggle to keep the press free. That struggle was not won with the constitutional guarantee of freedom of the press. Just for example, Huey Long is not long dead. There will always be men in government who deep in their hearts would like to have any criticism of their acts branded as sedition. What government, all the way from national governments down to small city governments, could do to hamstring a timid press with their regulatory, tax, and police powers, is well known to all astute newspaper men.

It is certain that the newspaper of tomorrow will be a far better newspaper. Most of us agree readily with our critics that we have been overconcerned with reporting those things which involve merely novelty, shock, violence or conflict. The oldtime newspaper man who insists that a news sense is something intuitive, something which escapes definition, is going out of date. There has been a sharp curtailment of the printing of crime news over the country. But whenever a particularly lurid crime is committed, it will be printed, because you and I will grab our papers and avidly read about it. Maybe we will then throw down our papers, and say to each other, "Why do they print such things!"

But today's newspaper man knows that whatever is happening or developing that is likely to affect you or me, is news. He knows, too, that we won't read a dull newspaper. If the subject matter is dull, he will use his ingenuity to make it interesting. Tomorrow, he will use more pictures, charts, diagrams and illustrations, many in full color. But he is also studying that type which he has always used, and he will make far better and more precise use of headlines. He will continue to use comics. Americans like comics. But the comics of tomorrow will be more sophisticated. Maybe even PhD's will like them. He will continue to devote space to Hollywood. As many Americans go to the movies as read newspapers. But I think his reporting from Hollywood will be far less naive.

But the main thing is, the newspaper of tomorrow will concentrate on the significant happenings all over the world. This world has grown small. The newspaper man will be increasingly better trained, better educated and more specialized. Even today, a great newspaper has a staff organized almost like a college faculty.

Mere routine reporting of facts will not be enough. That can only bring on that "crises of meaninglessness" of which Sevellon Brown warned the Press Institute. We will have far more conscientious, objective putting of the facts into perspective, more background and explanation. The process must necessarily be selective. The reader can absorb only so much.

The editorial page, which has languished on many newspapers since the waning of the era of individual journalism, will undoubtedly come back, as a medium of interpretation. Brown told a Press Institute seminar of editorial writers, "The expression of sound and tightly reasoned opinion will never twist the thinking of the reader. Its objective is the pursuit of truth."

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, AMERICAN PRESS INSTITUTE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

Next Month The MAGAZINE'S series will continue next month with a discussion of the Radio as a major channel of public opinion in a democracy. Two authorita- tive articles will be contributed by Cedric Foster '24, nationally known news commentator, and Jerry A. Danzig '34, program director of Station WINS in New York, who before his wartime radio service with the Navy was a direc- tor for Station WOR in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe American Press

February 1947 By CARL D. GROAT '11 -

Article

ArticleA Free Press?

February 1947 By A. J. LIEBLING '24 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1947 By FRED F. STOCK WELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

February 1947 By OSMUN SKINNER, RUPERT C. THOMPSON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

February 1947 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS

Article

-

Article

ArticleSecretaries Meetings

April 1939 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

August 1943 By George H. Tilton III, USNR -

Article

ArticleIN HER OWN WRIGHT

May/June 2009 By Lisel Murdock ’09 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticleLARGE NUMBER WORKING WAY

June 1938 By Ralph N. Hill '39 -

Article

ArticleConvocation

January 1942 By The Edrror.