ITHINK ALMOST EVERYBODY will grant that if candidates for the United States Senate were required to possess ten million dollars, and for the House one million, the year-in-year-out level of conservatism of those two bodies might be expected to rise sharply. We could still be said to have a freely-elected Congress: anybody with ten million dollars (or one if he tailored his ambition to fit his means) would be free to try to get himself nominated, and the rest of us would be free to vote for our favorite millionaires or even to abstain from voting. (This last right would mark our continued superiority over states where people are compelled to vote for the Government slate.)

In the same sense, we have a free press today. (I am thinking of big-city and middling-city publishers as members of an upper and lower house of American opinion.) Anybody in the ten-million dollar category is free to try to buy or found a paper in a great city like New York or Chicago, and anybody with around a million (plus a lot of sporting blood) is free to try it in a place of mediocre size like Worcester. Mass. As to us, we are free to buy a paper or not, as we wish.

In a highly interesting book, The FirstFreedom, Morris Ernst has told the story of the increasing concentration of news outlets in the hands of a few people. There are fewer newspapers today than in 1916, and fewer owners in relation to the total number of papers. Ernst refrains from any reflection on the quality of the ownership; he says merely that it is dangerous that so much power should be held by so few individuals. I will go one timid step further than Ernst and suggest that these individuals because of their economic position form a typical group and share a typical outlook.

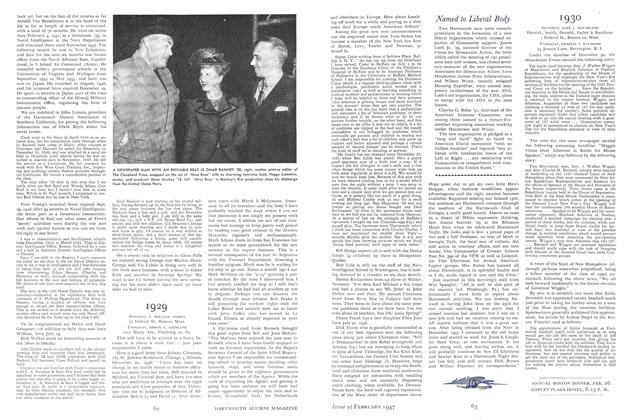

The newspaper owner is a rather large employer of labor. I don't want to bore you with statistics, but one figure that I remember unhappily is 2876, the number of us who lost jobs when the Pulitzers sold the World for salvage in 1931. He is nowadays forced to deal with unions in all departments of his enterprise, and is as unlikely as any other employer to be on their side. As owner of a large and profitable business he is opposed to Government intervention in his affairs beyond the maintenance of the subsidy extended to all newspapers through second-class mail rates. As an owner of valuable real estate he is more interested in keeping the tax rate down than in any other local issue. (Newspaper crusades for municipal "reform" are almost invariably tax-paring expeditions.) A planned economy is abhorrent to him, and since every other nation in the world above the rank of Transjordania has now gone in for some form of economic planning, the publisher has become our number one xenophobe. His "preference" for Socialist Britain over Communist Russia is only an inverse expression of relative dislike. It is based on the hope that continued financial intervention in Britain may prove more effectual than the 1919 military intervention in Russia. Because of publishers' wealth they do not have to be slugged over the head by "anti-democratic organizations" to force them into using their properties to form public opinion the N.A.M. approves. The gesture would be as redundant as twisting a nymphomaniac's arm to get her into bed. I am delighted that I do not have to insinuate that they consciously allow their output to be shaped by their personal interests. Psycho-analytical after-dinner talk has furnished us with a lovely word for what they do: they rationalize. And once a man has convinced himself that what is good for him is good for the herd of his inferiors, he enjoys the best of two worlds simultaneously, and can shake hands with Bertie McCormick, the owner of the Chicago Tribune.

The profit system, while it insures the predominant conservative coloration of our press, also guarantees that there will always be a certain amount of dissidence. The American press has never been monolithic, like that of an authoritarian state. One reason is that there is important money to be made in journalism by standing up for the underdog (demagogically or honestly, so long as the technique is good.) The underdog is numerous and prolific—another name for him is circulation. His wife buys girdles and baking powder and Literary Guild selections, and the advertiser has to reach her. Newspapers as they become successful and move to the right leave room for newcomers to the left. Marshall Field's Chicago Sun, for example, has acquired 400,000 readers in five years, simply because the Tribune, formerly alone in the Chicago morning field, had gone so far to the right. The fact that the Tribune's circulation has not been much affected indicates that the 400,000 had previous to 1941 been availing themselves of their freedom not to buy a newspaper. (Field himself illustrates another, less dependable, but nevertheless appreciable, favorable factor in the history of the American press—the occasional occurrence of that economic sport, the maverick millionaire.) E. W. Scripps was the outstanding practitioner of the trade of founding newspapers to stand up for the common man. He made a tremendous success of it, owning about twenty of them when he died. The first James Gordon Bennett's Herald, in the 40's, and Joseph Pulitzer's World, in the Bo's and 90's, to say nothing of the Scripps-Howard World-Telegram in 1927, won their niche in New York as left-of-center newspapers and then bogged down in profits.

Another factor favorable to freedom of the press, in a minor way, is the circumstance that publishers sometimes allow a certain latitude to employees in departments in which they have no direct interest—movies, for instance, if the publisher is not keeping a movie actress, or horse shows, if his wife does not own a horse. Musical and theatrical criticism is less rigorously controlled than it is in Russia.

The process by which the American press is pretty steadily revivified, and as steadily dies (newspapers are like cells in the body, some dying as others develop) was well described in 1911 by a young man named Joseph Medill Patterson, then an officer of the Chicago Tribune, who was destined himself to found an enormously successful paper, The Daily News of New York, and then within his own lifetime pilot it over the course he had foreshadowed. The quotation is from a play, The Fourth Estate, which Patterson wrote in his young discontent.

"Newspapers start when their owners are poor, and take the part of the people, and so they build up a large circulation, and, as a result, advertising. That makes them rich, and they begin, most naturally, to associate with other rich men—they play golf with one, and drink whiskey with another, and their son marries the daughter of a third. They forget all about the people, and then their circulation dries up, then their advertising, and then their paper becomes decadent." Patterson was not "poor" when he came to New York eight years later to start the News; he had the McCormick-Patterson Tribune fortune behind him, and at his side Max Annenberg, a high-priced journalistic condottiere who had already helped the Tribune win a pitched battle with Hearst in its own territory. But he was starting his paper from scratch, and he did it in the old dependable way, by taking up for the Common Manand sticking with him until 1940, by which time the uncommonly-successful-man contagion got him and he threw his arms around unregenerated Cousin Bertie's neck. The Tribune in Chicago and the News in New York have formed a solid front ever since. Patterson was uninfluenced by golf, whiskey, or social ambitions (he was a parsimonious, unsociable man, who cherished an illusion that he had already hit the social peak.) I think it is rather the complex of age, great wealth, a swelled head and the necessity to believe in the Heaven-decreed righteousness of a system which has permitted one to possess such power, that turns a publisher's head. The whiskey, weddings, yachts, horseshows, and the rest (golf no longer sounds so imposing as it did in 1911) are symptoms rather than causes.

Unfortunately, circulations do not "dry up" quickly, nor advertising fall away overnight. Reading a newspaper is a habit which holds on for a considerable time. So the erstwhile for-the-people newspaper continues to make money for a while after it changes its course. With the New YorkHerald this phase lasted half a century. It would, moreover, be difficult to fix the exact hour or day at which the change takes place: it is usually gradual, and perceptible to those working on the paper before it becomes apparent to the outside public. At any given moment there are more profitable newspapers in being than new ones trying to come up, so the general tone of the press is predominantly, and I fear increasingly, reactionary. (In New York, for example, of nine daily papers—there were 13 when I came up to college—seven are in the black and complacent, while only one, PM, which has not yet climbed out of the red, is fighting the good fight. A ninth, the Post, has so recently made the financial grade that it doesn't quite seem to know whether it is for the status quo or agin it.) The difference between newspaper pub- lishers' opinions and those of the public is so frequently expressed at the polls that it is unnecessary to insist on it here.

Don't get me wrong, though. I don't think that the battle is futile. I remember when I was a freshman, in 1921, listening to a lecture by Professor Mecklin in a survey course called, I think, Citizenship, in which he told how most of the newspapers had misrepresented the great steel strike of 1919. The only one that had told the truth, he said, as I remember it, was the old World. (I have heard since that the St. Louis Post-Dispatch was good, too, but he didn't mention it). It was the first time that I really believed that newspapers lied about that sort of thing. I had heard of Upton Sinclair's book, The Brass Check, but I hadn't wanted to read it because I had heard he was a "Bolshevik." I came up to college when I was just under 16, and the family environment was not exactly radical. But my reaction was that I wanted some day to work for the World, or for some other paper that would tell the truth. The World did a damned good job, on the strikes and on the Ku Klux Klan and on prohibition and prison camps (in Florida, not Silesia) and even though the second-generation Pulitzers let it grow nambypamby and then dropped it in terror when they had had a losing year and were down to their last 16 millions, it had not lived in vain.

1 think that anybody who talks often with people about newspapers nowadays must be impressed by the growing distrust of the information they contain. There is less a disposition to accept what they say than to try to estimate the probable truth on the basis of what they say, like aiming a rifle that you know has a deviation to the right. Even a report in a Hearst newspaper can be of considerable aid in arriving at a deduction if you know enough about (a) Hearst policy (b) the degree of abjectness of the correspondent signing the report. Every now and then I write a piece for TheNew Yorker under the heading of "The Wayward Press" (a title for the department invented by the late Robert Benchley when he started it early in the New Yorker's history). In this I concern myself not with big general thoughts about Trends (my boss wouldn't stand for such), but with the treatment of specific stories by the daily (chiefly New York) press. I am a damned sight kinder about newspapers than Wolcott Gibbs is about the theatre, but while nobody accuses him of sedition when he raps a play, I get letters calling me a little pal of Stalin when I sneer at the New York Sun. This reflects a pitch that newspaper publishers make to the effect that they are part of the great American heritage with a right to travel wrapped in the folds of the flag like a boll weevil in a cotton boll. Neither theatrical producers nor book publishers, apparently, partake of this sacred character. I get a lot more letters from people who are under the delusion that I can Do Something About It All. These reflect a general malaise on the part of the newspaper-reading public, which I do think will have some effect, though not, God knows, through me.

I believe that labor unions, citizens' organizations and possibly political parties yet unborn are going to back daily papers. These will represent definite, undisguised points of view, and will serve as controls on the large profit-making papers expressing definite, ill-disguised points of view. The Labor Party's Daily Herald in England has been of inestimable value in checking the blather of the Beaverbrook-Kemsley-Rothermere newspapers of huge circulation. When one cannot get the truth from any one paper (and I do not say that it is an easy thing, even with the best will in the world, for any one paper to tell all the truth), it is valuable to read two with opposite policies to get an idea of what is really happening. I cannot believe that labor leaders are so stupid they will let the other side monopolize the press indefinitely.

I also hope that we will live to see the endowed newspaper, devoted to the pursuit of daily truth as Dartmouth is to that of knowledge. I do not suppose that any reader of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE believes that the test of a college is the ability to earn a profit on operations (with the corollary that making the profit would soon become the chief preoccupation of its officers). I think that a good newspaper is as truly an educational institution as a college, so I don't see why it should have to stake its survival on attracting advertisers of ball-point pens and tickets to Hollywood peep-shows. And I think that private endowment would offer greater possibilities for a free press than State ownership (this is based on the chauvinistic idea that a place like Dartmouth can do a better job than a State University under the thumb of a Huey Long or Gene Talmadge). The hardest trick, of course, would be getting the chief donor of the endowment (perhaps a repentant tabloid publisher) to: (a) croak, or (b) sign a legally binding agreement never to stick his face in the editorial rooms. The best kind of an endowment for a newspaper would be one made up of several large and many small or mediumsized gifts (the Dartmouth pattern again). Personally, I would rather leave my money for a newspaper than for a cathedral, a gymnasium or even a home for street- walkers with fallen arches, but I have seldom been able to assemble more than $4.17 at one time.

THE NEW YORKER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe American Press

February 1947 By CARL D. GROAT '11 -

Article

ArticleYour Newspaper and You

February 1947 By CLAUDE A. JAGGER '24 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1947 By FRED F. STOCK WELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

February 1947 By OSMUN SKINNER, RUPERT C. THOMPSON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

February 1947 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS