One of the Great Wartime Engineering Triumphs, In Which Dartmouth Men Had a Hand, Remains As a Fascinating Route to Our "Last Frontier"

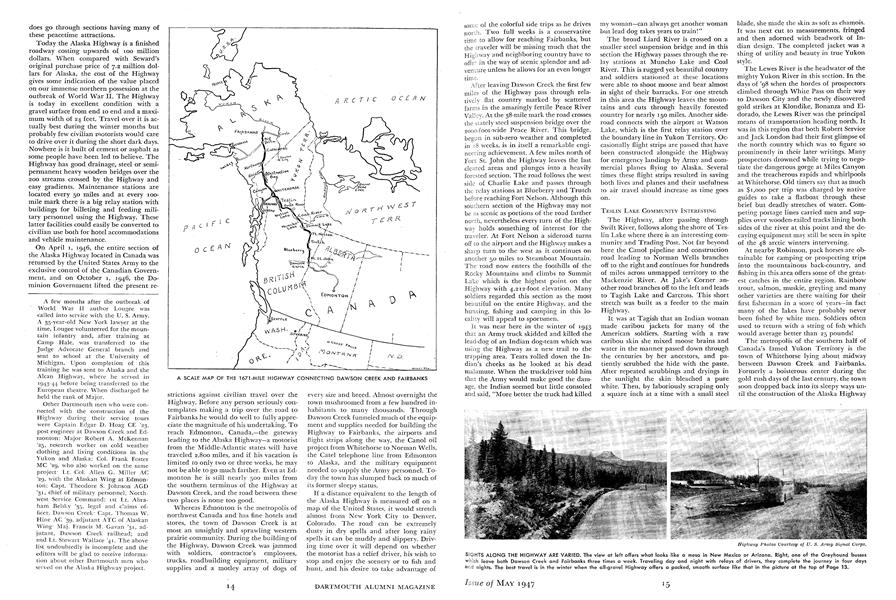

THE costly engineering feats of wartime are more often than not a total loss in the days of peace which follow. However, one superhuman achievement, pushed through in the face of threatened Jap invasion, remains today as a residual asset which will undoubtedly be an important factor in the future development and defense of the North American Continent. This invaluable asset is the Alaska Highway, winding its 1671-mile way through the wilderness from Dawson Creek to Fairbanks and providing for the first time an all-land route to our far-flung Territory of Alaska.

Dartmouth men and others drawn by the lure of the romantic north country see the Highway also as the road to a frontier land offering great attractions to the traveler and the sportsman. One purpose of this article is to answer some of their questions about the Highway and the possibility of driving over it to Alaska. The following account of what the traveler will encounter on his trip from Dawson Creek to Fairbanks might hold interest also for those who plan to stay home, for the Highway itself is a fascinating route and its building will always be one of the great stories of the war.

The construction of the 1671-mile-long Alaska Highway is an epic of engineering achievement. The Engineer troops, both white and colored, who pushed through the pioneer road in six months encountered almost unbelievable weather and living conditions; sleeping in tents at 50° below zero; wading through ice-cold mountain streams while surveying; frozen hands and feet and faces; ice and snow and more ice and more snow; and in the summertramping through mosquito infested muskeg swamps; choking dust from hundreds of trucks and bulldozers; barges capsizing and drowning their crews in the foaming whirlpools; accidents on the Highway itself—all these and many more hardships were the inevitable accompaniment of this undertaking. The little white crosses in the military and civilian cemeteries along the Highway stand as mute evidence of the toll exacted in completing the new military roadway ahead of schedule in order that the Japs might not get a foothold on this Continent.

In those early days of the War, military strategy called for immediate completion of a chain of airports between Edmonton, in Canada, and Fairbanks, Alaska, which had been started as a joint CanadianUnited States defense measure in 1941. To complete these airfields and to construct others in an almost totally unmapped wilderness stretching thousands of miles into sub-arctic country, a connecting roadway was necessary for emergency purposes and also to serve as an additional means of transporting troops and equipment to Alaska. The Army engineers, in selecting the route to be followed, were guided solely by military exigencies. It had to be a road which would be protected against Jap landings on the West Coast; one which would take advantage of the best weather conditions throughout an all-year operation; and a route which would follow the easiest terrain for construction purposes. Muskeg, those treacherous bogs of unknown depth, had to be avoided where- ever possible. No consideration was given to constructing the Highway through scenic country or regions where fishing and big-game hunting could be enjoyed, but fortunately for posterity the route chosen does go through sections having many of these peacetime attractions.

Today the Alaska Highway is a finished roadway costing upwards of 100 million dollars. When compared with Seward's original purchase price of 7.2 million dollars for Alaska, the cost of the Highway gives some indication of the value placed on our immense northern possession at the outbreak of World War 11. The Highway is today in excellent condition with a gravel surface from end to end and a maximum width of 24 feet. Travel over it is actually best during the winter months but probably few civilian motorists would care to drive over it during the short dark days. Nowhere is it built of cement or asphalt as some people have been led to believe. The Highway has good drainage, steel or semipermanent heavy wooden bridges over the 300 streams crossed by the Highway and easy gradients. Maintenance stations are located every 50 miles and at every 100mile mark there is a big relay station with buildings for billeting and feeding military personnel using the Highway. These latter facilities could easily be converted to civilian use both for hotel accommodations and vehicle maintenance.

On April 1, 1946, the entire section of the Alaska Highway located in Canada was returned by the United States Army to the exclusive control of the Canadian Government, and on October 1, 1946, the Dominion Government lifted the present restrictions against civilian travel over the Highway. Before any person seriously contemplates making a trip over the road to Fairbanks he would do well to fully appreciate the magnitude of his undertaking. To reach Edmonton, Canada,—the gateway leading to the Alaska Highway—a motorist from the Middle-Atlantic states will have traveled a,BOO miles, and if his vacation is limited to only two or three weeks, he may not be able to go much farther. Even at Edmonton he is still nearly 500 miles from the southern terminus of the Highway at Dawson Creek, and the road between these two places is none too good.

Whereas Edmonton is the metropolis of northwest Canada and has fine hotels and stores, the town of Dawson Creek is at most an unsightly and sprawling western prairie community. During the building of the Highway, Dawson Creek was jammed with soldiers, contractor's employees, trucks, roadbuilding equipment, military supplies and a motley array of dogs of every size and breed. Almost overnight the town mushroomed from a few hundred inhabitants to many thousands. Through Dawson Creek funneled much of the equipment and supplies needed for building the Highway to Fairbanks, the airports and flight strips along the way, the Canol oil project from Whitehorse to Norman Wells, the Catel telephone line from Edmonton to Alaska, and the military equipment needed to supply the Army personnel. Today the town has slumped back to much of its former sleepy status.

If a distance equivalent to the length of the Alaska Highway is measured off on a map of the United States, it would stretch almost from New York City to Denver, Colorado. The road can be extremely dusty in dry spells and after long rainy spells it can be muddy and slippery. Driving time over it will depend on whether the motorist has a relief driver, his wish to stop and enjoy the scenery or to fish and hunt, and his desire to take advantage of some of the colorful side trips as he drives north. Two full weeks is a conservative time to allow for reaching Fairbanks, but the traveler will be missing much that the Highway and neighboring country have to offer in the way of scenic splendor and adventure unless he allows for an even longer time.

After leaving Dawson Creek the first few miles of the Highway pass through relatively flat country marked by scattered farms in the amazingly fertile Peace River Valley. At the 38-mile mark the road crosses the stately steel suspension bridge over the 2000-foot-wide Peace River. This bridge, begun in sub-zero weather and completed in 18 weeks, is in itself a remarkable engineering achievement. A few miles north of Fort St. John the Highway leaves the last cleared areas and plunges into a heavily forested section. The road follows the west side of Charlie Lake and passes through the relay stations at Blueberry and Trutch before reaching Fort Nelson. Although this southern section of the Highway may not be as scenic as portions of the road farther north, nevertheless every turn of the Highway holds something of interest for the traveler. At Fort Nelson a sideroad turns off to the airport and the Highway makes a sharp turn to the west as it continues on another 50 miles to Steamboat Mountain. The road now enters the foothills of the Rocky Mountains and climbs to Summit Lake which is the highest point on the Highway with 4,212-foot elevation. Many soldiers regarded this section as the most beautiful on the entire Highway, and the hunting, fishing and camping in this locality will appeal to sportsmen.

It was near here in the winter of 1943 that an Army truck skidded and killed the lead-dog of an Indian dog-team which was using the Highway as a new trail to the trapping area. Tears rolled down the Indian's cheeks as he looked at his dead malamute. When the truckdriver told him that the Army would make good the damage, the Indian seemed but little consoled and said, "More better the truck had killed my woman—can always get another woman but lead dog takes years to train!"

The broad Liard River is crossed on a smaller steel suspension bridge and in this section the Highway passes through the relay stations at Muncho Lake and Coal River. This is rugged yet beautiful country and soldiers stationed at these locations were able to shoot moose and bear almost in sight of their barracks. For one stretch in this area the Highway leaves the mountains and cuts through heavily forested country for nearly 150 miles. Another sideroad connects with the airport at Watson Lake, which is the first relay station over the boundary line in Yukon Territory. Occasionally flight strips are passed that have been constructed alongside the Highway for emergency landings by Army and commercial planes flying to Alaska. Several times these flight strips resulted in saving both lives and planes and their usefulness to air travel should increase as time goes on.

TESLIN LAKE COMMUNITY INTERESTING

The Highway, after passing through Swift River, follows along the shore of Teslin Lake where there is an interesting community and Trading Post. Not far beyond here the Canol pipeline and construction road leading to Norman Wells branches off to the right and continues for hundreds of miles across unmapped territory to the Mackenzie River. At Jake's Corner another road branches off to the left and leads to Tagish Lake and Carcross. This short stretch was built as a feeder to the main Highway.

It was at Tagish that an Indian woman made caribou jackets for many of the American soldiers. Starting with a raw caribou skin she mixed moose brains and water in the manner passed down through the centuries by her ancestors, and patiently scrubbed the hide with the paste. After repeated scrubbings and dryings in the sunlight the skin bleached a pure white. Then, by laboriously scraping only a square inch at a time with a small steel blade, she made the skin as soft as chamois. It was next cut to measurements, fringed and then adorned with beadwork of Indian design. The completed jacket was a thing of utility and beauty in true Yukon style.

The Lewes River is the headwater of the mighty Yukon River in this section. In the days of '9B when the hordes of prospectors climbed through White Pass on their way to Dawson City and the newly discovered gold strikes at Klondike, Bonanza and Eldorado, the Lewes River was the principal means of transportation heading north. It was in this region that both Robert Service and Jack London had their first glimpse of the north country which was to figure so prominently in their later writings. Many prospectors drowned while trying to negotiate the dangerous gorge at Miles Canyon and the treacherous rapids and whirlpools at Whitehorse. Old timers say that as much as $l,OOO per trip was charged by native guides to take a flatboat through these brief but deadly stretches of water. Competing portage lines carried men and supplies over wooden-railed tracks lining both sides of the river at this point and the decaying equipment may still be seen in spite of the 48 arctic winters intervening.

At nearby Robinson, pack horses are obtainable for camping or prospecting trips into the mountainous back-country, and fishing in this area offers some of the greatest catches in the entire region. Rainbow trout, salmon, muskie, greyling and many other varieties are there waiting for their first fisherman in a score of years—in fact many of the lakes have probably never been fished by white men. Soldiers often used to return with a string of fish which would average better than 25 pounds!

The metropolis of the southern half of Canada's famed Yukon Territory is the town of Whitehorse lying about midway between Dawson Creek and Fairbanks. Formerly a boisterous center during the gold rush days of the last century, the town soon dropped back into its sleepy ways until the construction of the Alaska Highway suddenly jumped its population of 500 to well over 10,000 during the War. The Highway skirts the town and the motorist must drive down Mile Long Hill and past the Canol Oil Refinery to reach the business center on the banks of the Lewes River.

Here is the terminus of the narrow-gauge railroad from Skagway, Alaska, whose 110 miles of track played such an important part in the building of the Highway. No one will ever regret having left his auto in Whitehorse while making this scenic trip over the Rockies on the train. The railroad skirts famous Lake Bennett with its waters of unforgettable arctic blue-green and at whose head stands still the picturesque remains of the old log church. This edifice was built by the gold rush prospectors while awaiting transportation down the Lewes River and today the old church is the only remnant of what once was a town of nearly ten thousand souls. Walking along the shore of the lake a visitor can still pick up many souvenirs that have lain there untouched since those historic days of '98.

OLD '98 TRAIL STILL VISIBLE

The train ride across the Continental Divide through White Pass and down the steep slopes to tidewater provides scenery long to be remembered. The old Trail of '98 is still visible and the traveler can almost visualize the long line of men and beasts struggling up that narrow winding path in the dead of winter. It is hard to believe that the headwaters of the Yukon River which rise in this section only 18 miles from the Pacific Ocean must travel nearly 2,000 miles to finally reach the Pacific at the Bering Sea. Skagway, at the other end of the railroad, is a historic town at the head of the Inland Waterway. Here the mountains "seem to perpetually threaten to crush down upon the town and the roaring waterfalls literally tumble out of the sky.

Whitehorse is also the starting point for the steamers which ply back and forth to Dawson City on the Yukon, The town of Whitehorse consists mainly of log structures with grass roofs. The old Log Church where Robert Service once served as a vestryman is one of the historical spots worthy of a visit and directly across the street is the legendary cabin of "Sam McGee" who, according, to the poem, was cremated on the shores of neighboring Lake Leßarge. The town also boasts of a comfortable hotel and restaurant. The atmosphere of the north country makes itself felt here at the sight of Eskimo and Malamute dogs accompanied by Indian children. It was in this section that the United States Army obtained scores of huge pack-dogs which were shipped to Camp Rimini in Montana for training with Kg units for plane rescue work in Labrador, Greenland and Iceland.

The Indian population in and around Whitehorse is large and the presence of the red-coated "Mounties" adds to the feeling that at last you have reached a frontier town. Much time could be spent here exploring the neighboring country, visiting abandoned mines and chatting with the few remaining survivors of the '98 gold rush. Some of these old fellows still live alone in log cabins near the river and spend every summer prospecting for the elusive golden metal. If the traveler is a fly-fisherman he will find the greyling in the Lewes River and in nearby streams a tasty catch, but a headnet will be his best friend against the hordes of mosquitoes while he is wading.

From here the Highway continues northward through interesting and scenic country. The village of Champagne has associated with it a strange tale. Each fall the herd of horses owned by the natives in the village, instead of being shut up in barns as protection against the arctic winter blizzards, are turned loose to browse where they will, far up in the mountain canyons. A green moss under the snow provides their fodder. When attacked by wolves, the horses stand back to back in a circle and fight off their assailants. The horses have survived many a winter in this fashion and in the spring a round-up is staged to find the horses and bring them back to the village for the summer tasks.

The next relay station is located at Canyon, where there is an excellent trout fishing stream. In this section there are occasionally trappers' cabins close to the Highway. A few minutes' pause at some of these cabins will bring forth many stories of adventure in the north country. Near here the so-called "Cut-Off" enters the Highway from Haines, Alaska. Originally this cutoff was constructed as part of the Highway in order to save considerable distance between the end of the Inland Waterway and Fairbanks.

An interesting story is told about this Haines Cut-Off. The Army Post at Haines is the oldest military reservation in Alaska. Some years ago a Regular Army sergeant who had spent most of his years of service at Haines, decided to retire. Having become fond of the neighboring country he trudged his way inland for many miles so as to be assured privacy and then built a log cabin as a homestead. His only trips to civilization were the yearly treks to Haines to obtain supplies—mainly tobacco. He wanted solitude and he had found it. Then one day in 1943 he was surprised to find surveyers running levels past his front door and not long afterwards the bulldozers came along knocking down everything in front of them. For days he stood in his doorway and silently watched the men and trucks engaged in the roadbuilding. His silhouette in the doorway was a familiar picture to the men on the road. Then for several days he was not seen and when an inquisitive truck-driver finally investigated, the body of the old soldier was found hanging by the neck from the rafters of his cabin. He had been unable to stand the sight of civilization pushing so close to him. The ironic part of the story is that if the old veteran had waited only a few months more he would have seen the Haines Cut-Off temporarily abandoned because of the severe winter storms, and today the Canadian government is even threatening the complete abandonment of its portion of the Cut-Off, which would return the area to its primeval state.

Where the Haines Cut-Off joins the Alaska Highway there are a few log cabins which comprise one of the oldest Trading Posts in this region. The widow who now runs the Post alone originally came into the valley by dog-team with her husband. After his death she decided to carry on the Trading Post for the benefit of the few natives nearby. She is a graduate of an American university and even holds a post-graduate degree. The high mountains to the West which practically rise in her front yard hold very few secrets from her, and her stories of the early days in these mountains reveal her true pioneer spirit. Even today at an advanced age this remarkable woman likes nothing better than to take her dog and gun and hunt for mountain sheep and goats in their mountain fastnesses. When you knock at her door, if she is not inside the Trading Post, then look for her down by the brook where she has a fine garden .... or possibly she has gone hunting for a few days.

Beautiful Lake Kluane is skirted by the Highway and a short visit to the old log settlement at the southern end of the lake is well worth while. Here lives an elderly hunter and trapper who first came into the country during the gold rush of '98 and who finally drifted north to the Eskimo settlement of Old Crow near the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Bringing back with him an Eskimo wife, this early settler has since enjoyed the reputation of being one of the best guides for big-game hunting in the Yukon. Several of his shacks are filled with the trophies of many hunts including record-size moose, caribou, grizzlies, elk, mountain goat and mountain lion. It is with a twinkle in his eye that he likes to pull back the curtain in a corner of his cabin to reveal an antiquated porcelain bath-tub that was brought in by dog-sled many years ago. He chuckles when he says, "Yes, we take a bath every year or two whether we need it or not!" That tub being one of the show places in the district, it is safe to wager that it has seen much service over the years.

Kluane Lake offers one of the most picturesque camping places along the entire Highway. The Canadian Government has established a Park at this place because of its undisturbed beauty. The river which flows into the lake from the west finds its headwaters at the base of towering Mt. St. Elias whose 18,008 ft. altitude makes it the third highest peak on the Continent. The snow-covered mountains which rim the lake cast motionless reflections in the blue-green water and a camera enthusiast will have to search long and far to find better subjects for his colored film. And here is the place to try your luck at lake fishing. Use a wet streamer fly with a small spinner and you'll have no trouble in catching some big ones. During the summer months it is light enough at midnight to still take pictures and only by keeping close tabs on his watch does a person know it is time to get some sleep.

A short stop should by all means be made at Soldier's Summit overlooking Kluane Lake. It is only a few yards' climb from the present roadway and a fine panorama spreads out to the east and south. It was here on November 20, 1942, that the official dedication ceremonies of the Alaska Highway took place before a small group of Canadians and Americans who stood shivering in the biting 15-below-zero wind.

Heading north again, the motorist passes through the relay stations at Destruction Bay and Koidern before reaching the boundary between Alaska and Canada. This is a rugged mountainous section with fine scenery at every turn of the road. Steel bridges placed on concrete piers span the roaring mountain streams. The boundary itself is marked by only a small sign but as a person stands in the roadway and looks north and then south he will see that a swath has been cleared as far as the eye can see. From here on the country flattens out as the Highway approaches Northway, the first relay station in Alaska. The road here follows the eastern rim of a broad valley and a fine view extends to the west across the taiga to the snow-capped peaks in the far distance.

The relay station at Cathedral Bluffs is nestled between high mountains but the next relay station at Big Delta is out on a flat stretch where the wind never ceases to blow. Even in the winter the snow is all blown away from the Highway and bare ground shows for miles. It is at Big Delta that the Richardson Highway branches off to Valdez on the southern coast of Alaska. Valdez is an ice-free port and Anchorage has taken advantage of that by building the new Glenn Highway to connect with it. From Big Delta the Alaska Highway follows the old Richardson Highway which has been straightened and widened. This is the Tanana Valley where in summer months the Alaska fireweed grows in a riot of color as far as the eye can see.

As the motorist approaches Fairbanks he passes the tremendous new airport constructed by the Army on the flat stretches of tundra. Not far beyond, the Highway skirts Ladd Field which played such an important part in the delivery of fighting planes to Russia during the war. Fairbanks is a modern community with paved streets, Federal Courthouse, stores, hotels, theatre, newspaper and bank. However, the atmosphere of the arctic is present in the type of buildings and in the clothing of the inhabitants. Many of the structures are of log construction with grass roofs and the people wear parkas, mukluks or moccasins according to the season.

On the outskirts of Fairbanks are the buildings of the University of Alaska, the modern Experimental Farm where vegetables grow to almost unbelievable size in a very short time due to the long hours of summer sunlight, and the great goldfields where dredge mining is one of the Territory's major industries. On a clear day, from the campus of the University majestic Mt. McKinley, the highest peak on this Continent, can be seen far to the south towering 20,300 feet into the sky.

The Alaska Highway ends at Fairbanks and any person who has driven over it will agree that it represents one of the greatest engineering achievements of our time. A traveler who has not yet had his fill of driving can continue on to Livengood and to Circle Springs just over the Arctic Circle where the sun does not set during the long summer days. Or from Fairbanks planes will fly you to Nome, Anchorage, Point Barrow or almost any place in Alaska where a bush pilot can make a landing. Many visitors will find Fairbanks much to their liking. Gone are the days when the town was filled only with persons who wanted to strike it rich and then return to the States. Today the people who live in Fairbanks are serious-minded citizens who have chosen Alaska for their permanent home. They extend a welcome to new residents who are willing to meet the rigorous requirements of the north country and who seek a permanent home in that great Territory which has so much to offer in the way of abundant living.

International cooperation between Canada and the United States originally built the Alaska Highway during a period of emergency, and continued international cooperation during times of peace can keep it open for the benefit of all. The Highway can play an important part in the future development of not only Alaska but also the entire northwestern section of this Continent. And to the far-sighted, the upkeep of the Highway is a guarantee of the security of our great northern possession in times to come, especially against surprise attack from across the great arctic wastes which constitute the most direct route from northern and central Europe.

If you are one of those fortunate ones who someday have the privilege of drivingover the entire length of the Alaska Highway, just remember that it leads to our "Last Frontier" and to what may soon become the 49th State in the Union.

A SCALE MAP OF THE 1671-MILE HIGHWAY CONNECTING DAWSON CREEK AND FAIRBANKS

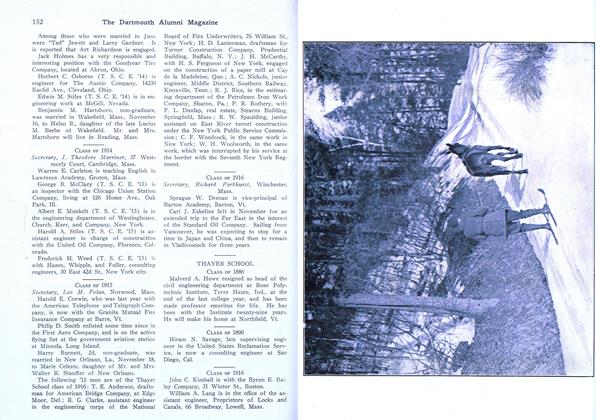

SIGHTS ALONG THE HIGHWAY ARE VARIED. The view at left offers what looks like a mesa in New Mexico or Arizona. Right, one of the Greyhound busses which leave both Dawson Creek and Fairbanks three times a week. Traveling day and night with relays of drivers, they complete the journey in four days and nights. The best travel is in the winter when the all-gravel Highway offers a packed, smooth surface like that in the picture at the top of Page 13.

MOST PHOTOGRAPHED SPOT on the Alaska Highway is this cluster of signs near Watson Lake. During the war it was a favorite subject of troops.

THE AUTHOR ON A HANOVER VISIT: During terminal leave in February 1946, Major Larry Lougee '29 returned to the spot where he learned some of the outdoor skills which proved valuable in the far north.

A few months after the outbreak of World War II author Lougee was called into service with the U. S. Army. A 35-year-old New York lawyer at the time, Lougee volunteered for the mountain infantry and, after training at Camp Hale, was transferred to the Judge Advocate General branch and sent to school at the University of Michigan. Upon completion of this training he was sent to Alaska and the Alcan Highway, where he served in 1943-44 before being transferred to the European theatre. When discharged he held the rank of Major. Other Dartmouth men who were connected with the construction of the Highway during their service tours were Captain Edgar D. Hoag CE '23, post engineer at Dawson Creek and Edmonton; Major Robert A. McKennan '25, research worker on cold weather clothing and living conditions in the Yukon and Alaska; Col. Frank Foster MC '29, who also worked on the same project' Lt. Col. Allen G. Miller AC '29, with the Alaskan Wing at Edmonton; Capt. Theodore S. Johnson AGD '3l, chief of military personnel, Northwest Service Command; Ist Lt. Abra- ham Belsky '35, legal and claims officer, Dawson Creek; Capt. Thomas W. Hine AC '39, adjutant ATC of Alaskan Wing Maj. Francis M. Gavan '31, adjutant, Dawson Creek railhead; and 2nd Lt. Stewart Wallace '41. The above list undoubtedly is incomplete and the editors will be glad to receive information about other Dartmouth men who served on the Alaska Highway project.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePROPAGANDA AND THE CRISIS

May 1947 By MICHAEL E. CHOUKAS '27 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleJames Parmelee Richardson

May 1947 By JOSEPH W. GANNON '99 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

May 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

May 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1947 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER