Dartmouth Sociologist, in Concluding Article of Series, Says Propaganda Forces Are Obstructing Democracy and Urges Public Exposure of Their Aims and Methods

THE PRECEDING PAPERS in this series amply justify the editor's original assumption that the contemporary transitional character of our Democracy is of such a nature that only the term crisis could properly describe it.

Professor Cantril aptly enough begins the series, and his article, with the rather startling statement that "It's a rare thing these days to find a complacent man.." Mr. Jagger tells us that "we live in a confused and conflict-torn world," and quoting a well-known journalist, Mr. Sevellon Brown of the Providence Journal, employs a most significant phrase, "the crisis of meaninglessness," to characterize the bewilderment of the contemporary newspaper man—a phrase I should like to return to presently. Further illustrating this spreading confusion among the men who operate our channels of information, and in a way epitomizing it. Mr. Danzig asks, rhetorically I presume: "Who in a democracy is to decide what it is that the public should think?" Who indeed!

I have been asked to describe the role that propaganda may be playing in this present crisis: the extent to which it has infiltrated into our channels of communication; the degree to which it is contributing to our mental confusion; and the ways in which it may be interfering with the proper functioning of public opinion and the normal evolution of the democratic process.

The conclusion that propaganda is something undesirable; and perhaps dangerous, is obviously reflected in the terminology just used to pose these basic questions. Infiltration into our channels of communication suggests intrusion of foreign matter—goals, purposes, and techniques different from the ones that these channels should "legitimately" possess within the framework of the democratic society. As a factor contributing to mental confusion, such infiltration would be both undesirable and dangerous in any type of society. Interfering with the processes of public opinion and thereby retarding, obstructing, and even preventing the natural unfolding of the democratic society, it automatically becomes a social force incompatible with and therefore inimical to the democratic ideal.

That this is a general and rather strong condemnation of propaganda I fully recognize. I am further conscious of the fact that the eyebrows of some of my readers may be lifted to some degree at this point. Perhaps I should say most. For, nowhere in our thinking do we show more confusion today than in our social relations—those of man to man, and the individual to the group and society. It is this confusion that has such a paralyzing effect upon our "news" men who with great sincerity and all the good will in the world attempt to inform the public, to give it accurate information, only to be faced with that wall of "meaninglessness"—a confusion which springs directly from that pernicious intellectual process which is so characteristic of our age, the gradual dilution of our intellectual concepts and values. Words are rapidly losing their sharpness of meaning or are being distorted, even perverted beyond recognition, while our values are being deprived of their vitality and strength as their intellectual foundations are thereby undermined.

To trace the social and psychological causes in our society which are largely responsible for this growing mental and moral disintegration and paralysis exceeds both in scope and purpose the boundaries of this article. For the most part this corroding process is being generated spontaneously and unintentionally by millions of daily acts of thoughtless and irresponsible individuals whose mental and moral horizons terminate at the point where private and immediate gains cease.

Not so spontaneous and unintentional, however, is the prevalent lack of understanding of the real nature of propaganda. Propagandists, someone has said, are an extremely "shy" lot. They are reluctant to part with information that might disclose the nature of their art or their goals. On the other hand, and no doubt in self defense, they deliberately set out to frustrate any effort to obtain a clear-cut, sharp concept of propaganda, by persistently reiterating the idea that propaganda is no different from other forms of promotional activity, or general publicity, or even Education. Absolute identification of propaganda with Education has officially been accepted and decreed by the totalitarian regimes, a fact of no little significance for us.

Equally significant is an observation made by a competent scholar of the field, the British journalist Richard S. Lambert, who in his challenging book entitled Propaganda concludes: "In an ideal world no propaganda would be necessary, because the individual would be able to recognize what was true and what was to his own interest." Mr. Lambert assumes this ideal world to be a society within which "men would be equal, independent, and self-reliant,"—a society interestingly enough not far removed from the one postulated by our democratic tradition and hopes.

The general aspects of the nature of propaganda and its social effects are definitely implied in this relation of propaganda to the totalitarian regimes on the one hand, and the kind of society the people with the democratic tradition are striving for, on the other. For our immediate purpose, however, which involves an estimate of the part propaganda is playing in the present crisis of Democracy, a more specific, sharper delineation of its chief attributes is required. We need a definition which should bring out its component parts, for these are the criteria which lead to its detection and an appreciation of its effects.

Propaganda may be defined as:

"The art of disseminating deliberately distorted information or manipulating valuesymbols with the intent of inducing a state of mind which may lead to action favorable to predetermined goals."

I am offering this definition as a safeguard against the universal skepticism and cynicism which inevitably accompany all promotional and publicity activities if we fail to draw the distinction between them and propaganda.

The propagandist is a disseminator of both news and opinions, and at times a manipulator of value-symbols. But because of the peculiarity of his art which is determined by the particularity of his objectives, he is forced to devise techniques of dissemination and develop attitudes about their validity which strongly differ from those of other disseminators, such as educators and "news" men.

For example, a newspaperman who has attained a high degree of objectivity in his reporting, to quote Mr. Jagger again, is "effectively performing his vital function in this democratic world." This standard of objectivity which is equally shared by educators is completely absent from the repertoire of rules and regulations of the propagandist. For the propagandist, the accuracy and validity of the material he is disseminating are of no concern. He is accurate only in the selection of those facts, opinions, or symbols which will persuade or provoke the recipient to that action which the propagandist considers imperat ive in terms of the interests he is serving. In that respect, propaganda is an applied science, for the propagandist cannot afford to misjudge either the workings of the human mind or the role that traditions play in controlling human behavior. Beyond that, the term accuracy has no meaning for the propagandist.

The cardinal distinction between the propagandist and other disseminators lies in the fact that he is forced to specialize in the dissemination of distorted information by the fact that he is serving special interests and not those of society as a whole. Being interested primarily and ultimately in the kind of action that would serve his own purposes, he presents to his target group a picture of an event or an issue which, if accepted, would turn the recipient into an unconscious collaborator. For the average person would not normally choose a line of action satisfactory to somebody else's special interest as against that of the whole if in possession of an undistorted picture of the situation or an untampered set of values. The distortion of facts so that the "proper" (from the propagandist's point of view) picture of a situation would be conveyed to those propagandized is the essence of propaganda.

Propaganda distortion should be further distinguished from the normal and natural degree of distortion which, due to the human inadequacy of expression, the inefficiency of our means of communication, or the complexity of human events, is an unavoidable concomitant of the process of human communication. Distortion in propaganda is deliberate, because it is calculated to induce a definite type of action. Distortions incurred in the normal practice of communicating with other people are unintentional and therefore uncontrolled, and in the long run they tend to cancel one another and be corrected by further investigation. From this point of view, the term "unintentional propaganda" is meaningless, and to the extent that it tends to protect the propagandist himself, somewhat dangerous.

In the detection of propaganda, the distinction is of fundamental importance, for it enables one to establish objective criteria. For instance, if distortion has been discovered in some material, the question arises as to whether it is deliberate or unintentional. If it is deliberate, an analysis will disclose certain uniformities. All the distortions, whether in the form of nonexistent facts or suppressed facts, will be driving the recipient to the same general conclusion and will be aiming at arousing his emotions in a certain definite direction. If it is unintentional, no such definite pattern will be apparent. Such is the first step in the analysis of propaganda.

After a propagandist has made a study of a situation and has prepared appropriate distortions (by exaggerating or minimizing certain aspects, omitting some and adding others), the first step in the distribution of his material is to devise methods that might enable him to present such material as unquestionably true—a toll imposed upon the propagandist by the fundamental rational nature of the human mind.

A large number of techniques is thus developed, aimed at establishing authenticity and credibility of the "facts" released through the channels of communication. Insistence upon the absolute accuracy of this information, consistent repetition, concealment of the real (propagandistic) source, and claims that such information springs from high-sounding centers of authority and prestige—all these and other devices are resorted to in an effort to achieve acceptance.

This intellectual groundwork, pouring into the minds of people the "right" kind of information, prepares the stage for the next and more spectacular scene, the manipulation of the value-symbols. Because emotional appeals now have to be made and continued concealment becomes extremely difficult, the popular notion has arisen that propagandists deal mostly with emotions, a notion that is likely to give one a false sense of security and dull his realization that danger may lurk in those previously established faulty intellectual assumptions. Long before the Nazi leaders were able to evoke those powerful emotional reactions from the Nazi youth at the mere dangling of the racial symbol, they had emptied into those youthful vacant heads the most unrealistic, monstrous notions about the nature of race under the guise of "scientific truth"—and left us with the enormous task of mental and moral reconstruction in the process.

But isn't it possible, one might ask, that a propagandist may sometimes tell the truth? It is. And if he does, he is one of two things: either a bad (inefficient) propagandist (and we shouldn't worry about him, for he sooner or later would commit other unpardonable blunders and will be found out), or an extremely subtle one, the most dangerous of his species. In the latter's case, the "truth" is only superficial and partial. It defines, accurately to be sure (and therein lies the danger), part of a given situation, but under conditions carefully calculated in advance to lead the unsuspecting victim to a general conclusion which he would not otherwise have reached. The propagandist's main objective here is to force his intended victim into a wrong evaluation of the situation by allowing him to 'see a meaning, to get a perspective that isn't there. So, though the given facts are not distorted, the significance of the situation is, and so is the victim's perspective.

This brief sketch on the nature of organized and coordinated deception which is propaganda may enable us to get a broader understanding of its role in the contemporary crisis.

Our crisis springs from the fact that our social world is a veritable jungle not unlike the natural one with which primitive man had to contend. We probably know as little about the source, the nature, and the direction of social forces that rise to smite us from time to time as he did about those of nature, and from all indications we are not enjoying a greater control over the social than he did over the natural.

Unlike primitive man, however, who seldom had the time to think of himself because of the constant demands of an exacting and apparently a hostile nature, we somehow have reached a stage where we can dream of an ideal Man, and an ideal World, at a time when we are apparently unprepared to set up a social order through which we could achieve those goals.

We have forged the Democratic ideal with the dignity of the individual as its central value and self-realization as a basic goal—a world which, if achieved, will consist of men who "would be equal, independent and self-reliant." But we still seem to be far removed from that social order, the Democratic Society, which could make realization of the ideal possible. We can only say at this stage, as Professor Cantril does, that it is the duty of every educated man to work for the establishment of "those conditions in society which will make it possible for a man's own purpose to become a value of society while still remaining a personal purpose."

Contemporary events make the advancement of the democratic process a difficult task. Internal strains are accentuated by external pressures released by systems aiming at divergent goals. Prejudice, hatred, and suspicion to an abnormal degree are infecting our economic, political, religious and social relations.

Propagandists aggravate the situation. They are undermining our faith in the democratic ideal by striking directly at its roots, the dignity of the human being. No dupe ever felt, or looked, dignified.

By their constant distortions of social realities and the fanning of human emotions, they are interfering with efforts to subject the social environment to some degree of control.

Our confusion today, the "meanmglessness" that confronts our "news" men, and much of the abnormally intense feeling that characterizes our group relations can be traced to propaganda sources.

How extensive is this pernicious influence? It would be impossible to say quantitatively. But one could get a very good estimate by looking at the lengthy lists of pressure groups and groups of all sorts who have a special cause to plead. It should be recalled that previous to the war about 700 such groups were spreading the fascist doctrine throughout the land. Many more than 700 propaganda groups are now spreading anti-democratic doctrines of various degrees and shades. Who can estimate their damage?

I can think of no description of our present dilemma more accurate and more succinct than the one Walter Lippmann gives us in his book, Public Opinion:

"Thus the environment with which our public opinions deal is refracted in many ways, by censorship and privacy at the source, by physical and social barriers at the other end, by scanty attention, by the poverty of language, by distraction, by unconscious constellations of feeling, by wear and tear, violence, monotony. These- limitations upon our access to that environment combine with the obscurity and complexity of the facts themselves to thwart clearness and justice of perception, to substitute misleading fictions for workable ideas, and to deprive us of adequate checks upon those who consciously strive to mislead."

It is the duty not only of every educated man but of every believer in the democratic ideal to help" to establish checks against those who "consciously strive to mislead." The pressure against Democracy from the outside is mounting. We ought not to permit disintegrating forces from within to remain uncontrolled and to increase.

There are some hopeful signs. Mr. Liebling in his article on the press suggests an "endowed newspaper" as a remedy against pressure from vested interests. Professor Cantril sees in the public opinion polls "one of the most valuable instruments yet discovered to speed the democratic process," for, he says, "one service that polls can provide is to counteract in part the influence of pressure groups."

A recent analysis of our media of communication, A Free and Responsible Press, suggests that "a new and independent agency to appraise and report annually upon the performance of the press" be established.

Such devices are of a remedial nature. We need preventive measures.

Mr. Liebling's "endowed newspaper" would probably be free from direct pressure, but it would be unable to avoid the indirect effects of the propagandists.

Professor Cantril, I'm afraid, is a little too optimistic. Public Opinion polls register the public's judgment on a special issue at a particular time. They fail to indicate whether, and to what degree, that judgment has been tampered with by interested parties. As a wise man once said, ".... You can fool All of the people some of the time " and time, in the predicament we are in, is of the essence.

The independent agency for an appraisal of the Press would be effective only to the extent that the standards it established for appraisal were sound and universally accepted by the Press world. But, from all indications, the confusion that now prevails in that world would make practically impossible the task of formulating such standards. But even if the task is accomplished, propagandists, both within and without the Press channels, have the technical means to circumvent them.

I frankly do not believe that any indirect assault would have much effect as a check against those who deliberately set out to mislead us. A direct attack could be launched against them by a privately endowed, independent agency whose main tasks would consist of compiling a list of all the propaganda groups in the country, analyzing their techniques, discovering their goals, and releasing the available information to government officials, to men responsible for our channels of communication, to men who measure public opinion, to colleges and universities, and to those pathetically few groups in the country who have undertaken to fight the battle of Democracy in a positive manner.

This I feel should be done before our crisis reaches climactic proportions—before the next depression.

THE EDITORS BELIEVE that the nine articles which have appeared in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE since January, under the general heading of Public Opinion ina Democracy, have served to point up a challenge for all educated men and women. If the functioning of democracy as we understand the term is dependent upon a public opinion that is freely and fully informed, can we find in the personal statements of these nine Dartmouth experts any real basis for feeling that this prime requisite of American democracy is as un trammeled as we would like to believe?

On the basis of what the MAGAZINE has printed in this series, these are questions that face men and women seriously interested in making our democracy work:

If, as Mr. Cantril says, American democracy is in transition and must change its superstructure or crack under pressure, is it in the hands of the public to set the direction of these changes?

Must we resort to comparison on the issue of the freedom of our press, reassuring ourselves with the fact that the American press is freer than any other in the world? Do we have a free press by our own democratic standards? Is there not danger in the growing concentration of large U. S. dailies in the hands of fewer and fewer publishers with the huge financial resources necessary for successful newspaper operation?

Can radio, now operating on a juvenile level established by commercial sponsors and hamstrung by governmental directives that no side be offended, fulfill a vital, adult role in American democracy without drastically raising the level of its performance?

How can the movies, for all their potentialities and technical skill, be a socially responsible medium if big-industry considerations keep them in box-office grooves that avoid rather than face the questions of the day?

And if all our channels of mass communication fall short of the freedom and responsibility asked by real democracy, who is more fundamentally to blame than the public, which fails to demand better efforts and to support them when it does get them?

Finally, if propaganda increasingly distorts the free flow of information and opinion, can we any longer allow these anti-democratic forces to operate unchecked and unidentified?

These are some of the questions which have been raised in the editors' minds by the statements of Dartmouth men on Public Opinion in a Democracy. Educated men, bearing a public responsibility for the simple reason that they are educated, must ponder these issues and press for answers—true democratic answers.

C. E. w.

PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

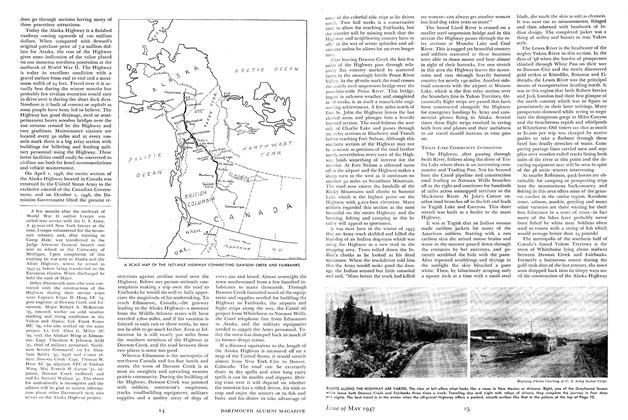

ArticleTHE ALASKA HIGHWAY

May 1947 By LAURENCE W. LOUGEE '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleJames Parmelee Richardson

May 1947 By JOSEPH W. GANNON '99 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

May 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

May 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1947 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER