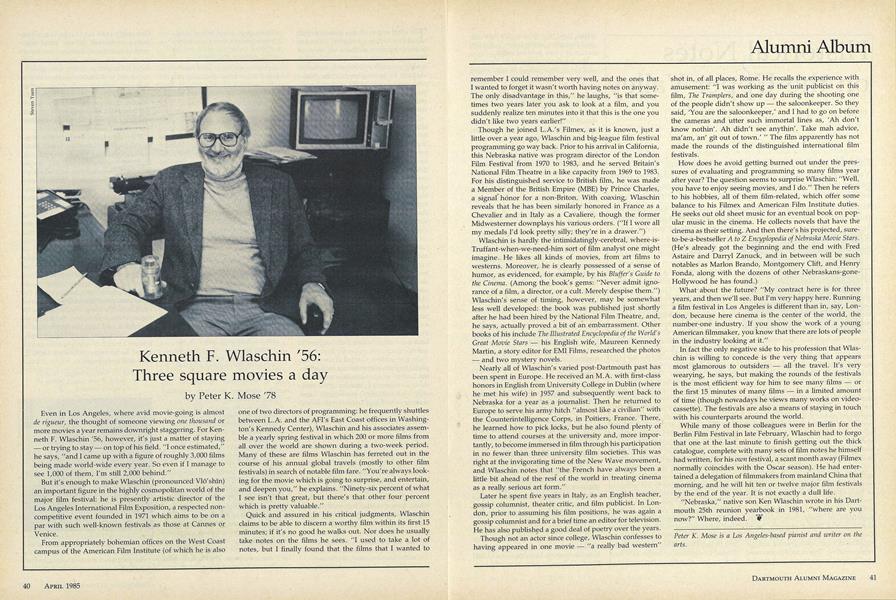

Even in Los Angeles, where avid movie-going is almost de rigueur, the thought of someone viewing one thousand or more movies a year remains downright staggering. For Kenneth F. Wlaschin '56, however, it's just a matter of staying or trying to stay on top of his field. "I once estimated," he says, "and I came up with a figure of roughly 3,000 films being made world-wide every year. So even if I manage to see 1,000 of them, I'm still 2,000 behind."

But it's enough to make Wlaschin (pronounced Vlo'shxn) an important figure in the highly cosmopolitan world of the major film festival: he is presently artistic director of the Los Angeles International Film Exposition, a respected noncompetitive event founded in 1971 which aims to be on a par with such well-known festivals as those at Cannes or Venice.

From appropriately bohemian offices on the West Coast campus of the American Film Institute (of which he is also one of two directors of programming: he frequently shuttles between L.A. and the AFl's East Coast offices in Washington's Kennedy Center), Wlaschin and his associates assemble a yearly spring festival in which 200 or more films from all over the world are shown during a two-week period. Many of these are films Wlaschin has ferreted out in the course of his annual global travels (mostly to other film festivals) in search of notable film fare. "You're always looking for the movie which is going to surprise, and entertain, and deepen you," he explains. "Ninety-six percent of what I see isn't that great, but there's that other four percent which is pretty valuable."

Quick and assured in his critical judgments, Wlaschin claims to be able to discern a worthy film within its first 15 minutes; if it's no good he walks out. Nor does he usually take notes on the films he sees. "I used to take a lot of notes, but I finally found that the films that I wanted to remember I could remember very well, and the ones that I wanted to forget it wasn't worth having notes on anyway. The only disadvantage in this," he laughs, "is that sometimes two years later you ask to look at a film, and you suddenly realize ten minutes into it that this is the one you didn't like two years earlier!"

Though he joined L.A.'s Filmex, as it is known, just a little over a year ago, Wlaschin and big-league film festival programming go way back. Prior to his arrival in California, this Nebraska native was program director of the London Film Festival from 1970 to 1983, and he served Britain's National Film Theatre in a like capacity from 1969 to 1983. For his distinguished service to British film, he was made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) by Prince Charles, a signal honor for a non-Briton. With coaxing, Wlaschin reveals that he has been similarly honored in France as a Chevalier and in Italy as a Cavaliere, though the former Midwesterner downplays his various orders. ("If I wore all my medals I'd look pretty silly; they're in a drawer.")

Wlaschin is hardly the intimidatingly-cerebral, where-isTruffant-when-we-need-him sort of film analyst one might imagine.. He likes all kinds of movies, from art films to westerns. Moreover, he is clearly possessed of a sense of humor, as evidenced, for example, by his Bluffer's Guide tothe Cinema. (Among the book's gems: "Never admit igno- rance of a film, a director, or a cult. Merely despise them.") Wlaschin's sense of timing, however, may be somewhat less well developed: the book was published just shortly after he had been hired by the National Film Theatre, and, he says, actually proved a bit of an embarrassment. Other books of his include The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the World'sGreat Movie Stars his English wife, Maureen Kennedy Martin, a story editor for EMI Films, researched the photos and two mystery novels.

Nearly all of Wlaschin's varied post-Dartmouth past has been spent in Europe. He received an M.A. with first-class honors in English from University College in Dublin (where he met his wife) in 1957 and subsequently went back to Nebraska for a year as a journalist. Then he returned to Europe to serve his army hitch "almost like a civilian" with the Counterintelligence Corps, in Poitiers, France. There, he learned how to pick locks, but he also found plenty of time to attend courses at the university and, more importantly, to become immersed in film through his participation in no fewer than three university film societies. This was right at the invigorating time of the New Wave movement, and Wlaschin notes that "the French have always been a little bit ahead of the rest of the world in treating cinema as a really serious art form."

Later he spent five years in Italy, as an English teacher, gossip columnist, theater critic, and film publicist. In London, prior to assuming his film positions, he was again a gossip columnist and for a brief time an editor for television. He has also published a good deal of poetry over the years.

Though not an actor since college, Wlaschin confesses to having appeared in one movie "a really bad western shot in, of all places, Rome. He recalls the experience with amusement: "I was working as the unit publicist on this film, The Tramplers, and one day during the shooting one of the people didn't show up the saloonkeeper. So they said, 'You are the saloonkeeper,' and I had to go on before the cameras and utter such immortal lines as, 'Ah don't know nothin'. Ah didn't see anythin'. Take mah advice, ma'am, an' git out of town.' " The film apparently has not made the rounds of the distinguished international film festivals.

How does he avoid getting burned out under the pressures of evaluating and programming so many films year after year? The question seems to surprise Wlaschin: "Well, you have to enjoy seeing movies, and I do." Then he refers to his hobbies, all of them film-related, which offer some balance to his Filmex and American Film Institute duties. He seeks out old sheet music for an eventual book on popular music in the cinema. He collects novels that have the cinema as their setting. And then there's his projected, sureto-be-a-bestseller A to Z Encyclopedia of Nebraska Movie Stars. (He's already got the beginning and the end with Fred Astaire and Darryl Zanuck, and in between will be such notables as Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, and Henry Fonda, along with the dozens of other Nebraskans-goneHollywood he has found.)

What about the future? "My contract here is for three years, and then we'll see. But I'm very happy here. Running a film festival in Los Angeles is different than in, say, London, because here cinema is the center of the world, the number-one industry. If you show the work of a young American filmmaker, you know that there are lots of people in the industry looking at it."

In fact the only negative side to his profession that Wlaschin is willing to concede is the very thing that appears most glamorous to outsiders all the travel. It's very wearying, he says, but making the rounds of the festivals is the most efficient way for him to see many films or the first 15 minutes of many films in a limited amount of time (though nowadays he views many works on videocassette). The festivals are also a means of staying in touch with his counterparts around the world.

While many of those colleagues were in Berlin for the Berlin Film Festival in late February, Wlaschin had to forgo that one at the last minute to finish getting out the thick catalogue, complete with many sets of film notes he himself had written, for his own festival, a scant month away (Filmex normally coincides with the Oscar season). He had entertained a delegation of filmmakers from mainland China that morning, and he will hit ten or twelve major film festivals by the end of the year. It is not exactly a dull life.

"Nebraska," native son Ken Wlaschin wrote in his Dartmouth 25th reunion yearbook in 1981, "where are you now?" Where, indeed.

Peter K. Mose is a Los Angeles-based pianist and writer on thearts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

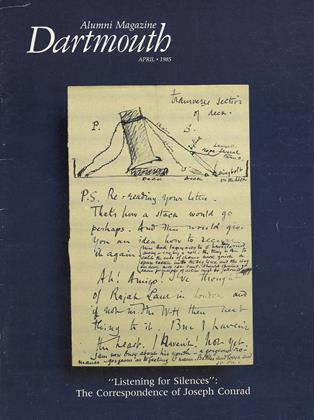

Cover StoryListening for the Silences

April 1985 By Laurence Davies -

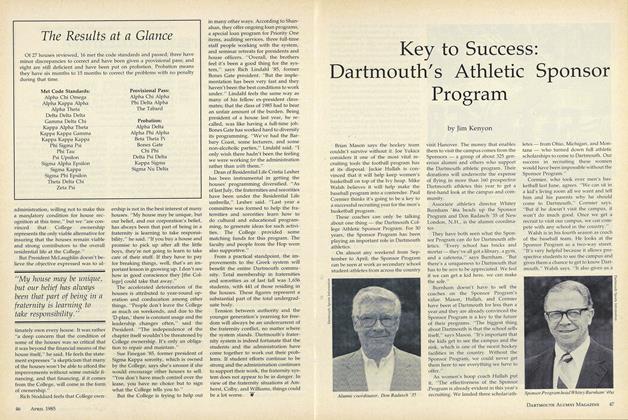

Feature

FeatureMinimum Standards

April 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

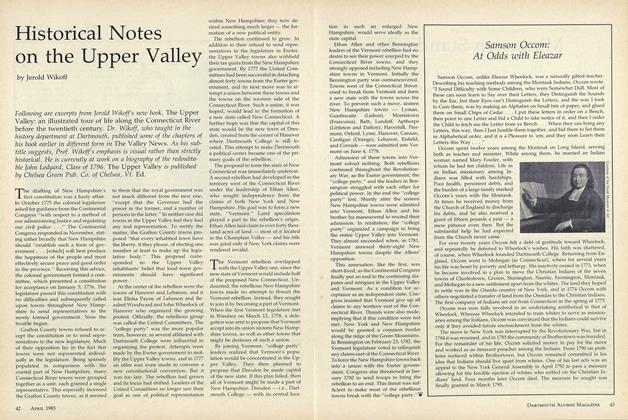

FeatureKey to Success: Dartmouth's Athletic Sponsor Program

April 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureHistorical Notes on the Upper Valley

April 1985 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureFROM THE DESK OF THE PRESIDENT

April 1985 -

Article

ArticleWorth his salt

April 1985 By JOseph Berman '86

Article

-

Article

ArticleIt Was Close

July 1961 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

December 1973 -

Article

ArticleThe Manley Weight Room

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleThe College in the Sixties

March 1940 By DR. WILLIAM LELAND HOLT -

Article

ArticleMedical School

March 1960 By HARRY W. SAVAGE, M'27 -

Article

ArticleMusic This Morning

APRIL 1971 By JOHN PARKE '39