President Dickey, at Exercises Opening the 179th Year, Recommends More Humble Approach to "The World"

MEN OF DARTMOUTH: THIS MORNING WE open the largest college in Dartmouth's 178 years. It may well be the biggest year she will ever know. Whether it will also be one of her great years is the real question, and history will record your answer to that question. From the day he matriculates, Dartmouth becomes both the opportunity and the responsibility of every Dartmouth man. From that moment on, what Dartmouth can mean to you is bounded only by what you personally are willing to be and also from that point on the College cannot in some measure escape sharing your fate individually and collectively. These, gentlemen, are not mere words of speech-making, they are the simple statement of the two really essential facts in the relationship between you and Dartmouth which this occasion symbolizes.

Whether men can be given much insight into such large propositions by telling I still do not know. Over the ages it has been traditional on these occasions for the speaker to display in glittering array the curative remedies to be had in education for the ills of the world. A quick look at the world today would lead most honest men to conclude one of three things about these past oratorical efforts directed at students: either they were magnificently dull speeches, or the diagnosis was faulty, or the educational remedies prescribed were just no good for what ailed the world. Having said that most honest men would so conclude, I now hasten to add that there are undoubtedly some honest men among us here today who would add a fourth alternative, namely, that the patient never touched the medicine.

Passing hastily, and without at least conscious elaboration, the possibility of dullness on the part of speechmakers, one might, I think, make a pretty good case for any or all of those other possible explanations of the present state of mankind's affairs. But with them all goes one more point. Today we use the term "the world" with what amounts to brash familiarity. Too often in speaking of such things as the world food problem, the world health problem, world trade, world peace and world government we disregard the fact that "the world" is a totality which in the domain of human problems constitutes the ultimate in degree of magnitude and degree of complexity. That is a fact, yes, but another fact is that almost every large problem today is in truth a world problem. Those two facts taken together provide thoughtful men with what might realistically be entitled an introduction to humility in curing the world's ills.

An introduction to humility, gentlemen, is a large part of any man's education. It is the surest solvent known for those two most persistent enemies of the educated man—pride and prejudice. Whether you are entering your first or your last term at Dartmouth, honest humility is a qualityworth your cultivation and your respect. I have no formula for either teaching or learning humility. I suspect there is none of general application. But I can suggest this. True humility is a hard thing to spot in others. Here, as with so many other things, a good place to begin is with yourself. When you have acquired that discipline of self which brings you occasionally to a conscious mental stop, you will soon begin to recognize the presence of humility, or even better, the lack of it, in yourself. As those occasions multiply, they will become less self-conscious and, other things being equal, you are on the road to becoming a thoughtful person who has some chance of getting at the essential working truths of our daily lives.

However essential humility may be to the good life and the pursuit of truth, I hardly think it is an end of itself. As Mr. Justice Holmes told us on his ninetieth birthday, "To live is to function," and I do not hesitate to remind you that Dartmouth's obligation to human society will only be met if her men leave Hanover Plain with the capacity and the will "to be doers of the word, and not hearers only." Yours will be the opportunity and the responsibility to make a difference in the world because you attended this college. How much of a difference you will make in the world largely depends on what you do here. And what you do here in turn depends on your ability to generate within yourself both a sense of purpose and the values by which to weigh your purpose. Those things are here for your taking. Could a man be offered more? I doubt you ever will be.

And now, gentlemen, as I have said to some of you twice before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:- First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way and "Good Luck!"

ON THE DAY following Dartmouth's convocation, President Dickey spoke at Bennington College at the inauguration of President Burkhardt. There he further developed his concept of the liberal arts college, in an address which follows in part:

"Is a free society adequately served today by a liberal arts education which leaves so many individual men and women who have enjoyed its privileges content to be, or incapable of being, other than 'innocent bystanders' in the arenas of democracy? I suggest to you that whatever else may be ahead, an institution such as the American liberal arts college is not likely to thrive within a society characterized by expanding democracy at every point unless the human products of that institution, to put it bluntly, count for more in the democratic process than carriage-trade votes on election day. For my part, I am pretty well convinced that essential as it is for our students to be introduced to the ways of individual contentment and expression, it is not enough. In a different society, at a different stage in human history, such a goal might well have been, and in the distant future may well again be, an adequate primary purpose for the liberal arts college. But it is far from adequate for our society and for our time.

"Despite occasional disturbing evidence to the contrary, I believe the central characteristic of our society today is the extension of the democratic process. More and more matters are coming under the control of more and more people.

"I also believe that the distinctive characteristic of our time is the urgency and the magnitude of the decisions which are now in human hands.

"It seems to me manifest that in such a society and at such a time there is only one chance of success. We must develop a leadership within the democratic process itself which has both the capacity and the will to provide solutions which fit our problems rather than the prejudices and shibboleths of the past. This occasion neither permits nor, I hope, requires further specification of the nature of these problems, but this much more might be worth saying about the place of leadership in the business. The concept of the nature and the purpose of leadership has been kicked around to the point where all meaning has worn off the word. It has become one of those words which has a painless—and an uneventful—passage through the human mind. I shall mention here only two aspects of the leadership of which I speak. First, as to its nature. It must fit the context of our political traditions and the American facts of life. That means it must be decentralized leadership, strong in the home communities and the organized special interest groups of American life. If there is strong, enlightened leadership on our great issues at this level, we can, I think, leave the big 'L' leadership in Washington to what we are pleased to call politics with, perhaps, just a mite of intervention by Providence at the worst moments. Secondly, a word as to the purpose of leadership. I believe that in the affairs of men leadership is primarily significant as a counterbalance to the time factor. It is the indispensable element in the solution of any large problem in the domain of human affairs, if time is really of the essence in the business.

"And now I must forego the luxury of further indulgence in certitude. I am not sure how you go about educating for the community leadership of which I've spoken. I shall spare you all my hunches on it, except one. You here at Bennington and many elsewhere have placed great emphasis on the individual program. In penology we called it "individualization of treatment." I believe in it for students as well as prisoners, but I also have a strong hunch that the individual program will be an inadequate program, so far as society's prime needs today are concerned, unless it has in it intellectual experiences, shared in common by all of our students and directed at the development of a heightened sense of individual public-mindedness and a greater sense of common public purpose. The common experience is still probably the tap root of cooperative living."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT IS A GREAT ISSUE ?

November 1947 By ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe, Undergraduate Chair

November 1947 By JOHN P. STEARNS '49. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1947 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

November 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

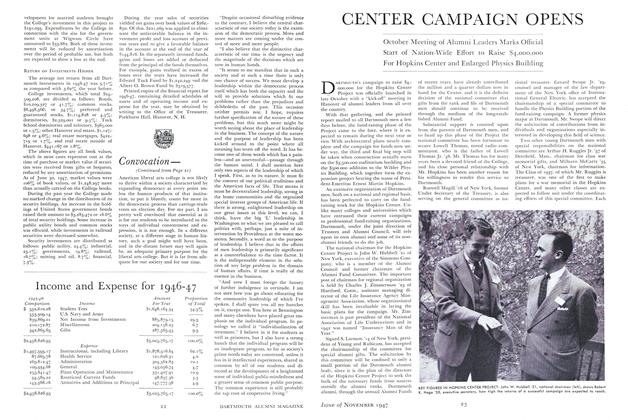

Article

ArticleCENTER CAMPAIGN OPENS

November 1947

Article

-

Article

ArticleENGLISH SPEAKING UNION RECEIVES LIBRARY FUNDS

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

ArticleCabin Contest

April 1939 -

Article

ArticleToxic Metals Endanger Environment

OCTOBER 1970 -

Article

ArticleReunion Week

JULY 1972 -

Article

ArticleTuck School Author

FEBRUARY 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

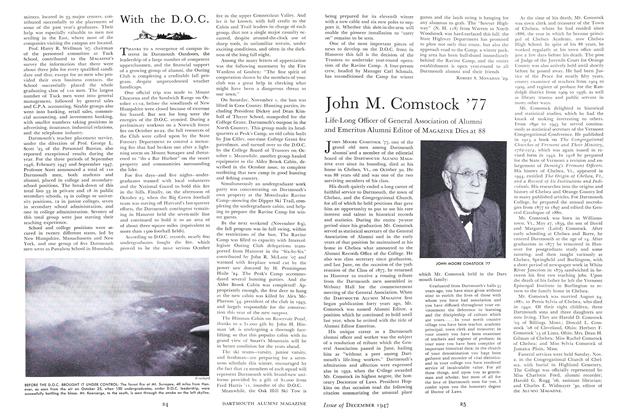

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

December 1947 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29.